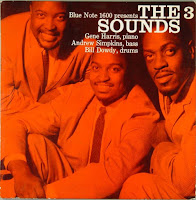

Introducing The Three Sounds

Released - February 1959

Recording and Session Information

Van Gelder Studio, Hackensack, NJ, September 16, 1958

Gene Harris, piano; Andrew Simpkins, bass; Bill Dowdy, drums.

tk.5 Willow Weep For Me

tk.6 Both Sides

tk.12 Tenderly

tk.17 It's Nice

Van Gelder Studio, Hackensack, NJ, September 28, 1958

Gene Harris, piano, celeste; Andrew Simpkins, bass; Bill Dowdy, drums.

tk.4 O Sole Mio

tk.7 Blue Bells

tk.12 Woody'n You

tk.18 Goin' Home

Track Listing

| Side One | ||

| Title | Author | Recording Date |

| Tenderly | Walter Gross, Jack Lawrence | 16/09/1958 |

| Willow Weep For Me | Ann Ronell | 16/09/1958 |

| Both Sides | Gene Harris | 16/09/1958 |

| Blue Bells | Gene Harris | 28/09/1958 |

| Side Two | ||

| It's Nice | Gene Harris | 16/09/1958 |

| Goin' Home | Traditional | 28/09/1958 |

| Woody 'N You | Dizzy Gillespie | 28/09/1958 |

| O Sole Mio | Giovanni Capurro, Eduardo di Capua | 28/09/1958 |

Credits

Cover Photo: FRANCIS WOLFF Cover Design: REID MILES Engineer: RUDY VAN GELDER Producer: ALFRED LION Liner Notes: LEONARD FEATHER

Liner Notes

| Cover Photo: | FRANCIS WOLFF |

| Cover Design: | REID MILES |

| Engineer: | RUDY VAN GELDER |

| Producer: | ALFRED LION |

| Liner Notes: | LEONARD FEATHER |

IT has been characteristic of the delirious decade drawing to a close that the search for new jazz sounds has tended to reach farther and farther in the direction of tonal and instrumental novelty. The Fifties will be remembered as the years in which flutes, cellos, oboes and almost every other instrument known to man, but previously strange to jazz, began to be involved in the endless quest for novelty.

Fortunately there have been a few steadying influences. Along with the oddly-shaped groups that have changed the tonal palette of our music there have been a few impressively successful diehards that have had the courage to leave things as they are instrumentally, while showing which way they may move, creatively.

Such a unit is the new-to-records trio now introduced by Blue Note as The 3 Sounds.

Their advent will come as a complete surprise to most, since as can be gleaned from the biographical details that follow, they had very little exposure in any medium until the opportunity make an LP was presented to only a couple months ago.

The present group might well have called itself the Four Sounds Minus One, since on its formation in South Bend in 1956 it featured a tenor saxophonist. There were several changes in personnel while they worked around Ohio, gigging with Al Hibbler, Lester Young, Sonny Stitt and others. Finally the last tenor man left and they because the Three Sounds. Their new home base was Washington, D.C., where they worked for many months at the Spotlight and Hollywood clubs. Dowdy doubles as the group's business manager.

In September of 1958 they came to New York and were installed at a slightly remote spot on upper Broadway known as the Offbeat. It was here that I first heard them, playing sets by Stuff Smith. The group was impressive collectively and individually.

It is difficult to know whom to deal with first in introducing the members, since the Sounds are in every sense of the phrase a cooperative group.

Gene Harris, the pianist, and de facto musical director of group, was born September 1, 1933. Self taught, he began playing at nine and never had any music lessons. Boogie-woogie seared his psyche at an early stage, but after going through the Albert Ammons and Pete Johnson period he graduated into an affection for the Oscar Peterson and Erroll Garner approaches.

Harris entered the service on graduating in 1951 and belatedly earned a knowledge of reading and musical fundamentals with the 82nd Airborne Division Army Band. "I was helped greatly," he recalls, "by Warrant Officer Charlesworth, who was in charge of the band and played trumpet in it, and by Captain Mobley, who's now in charge of the Washington Naval School of Music. After I left the service in 1951, I toured the South and Midwest with various bands — Benny Stevenson's in Florida, Curtis Johnson's in Indiana, Benny Poole's around Michigan — until 1956, when the Sounds were organized."

Andrew Simpkins, the bassist, was born April 29, 192 in Richmond, Ind. His original instruments were clarinets, which he studied from the of ten, and piano, which he took up four years later. He played both instruments through junior high and high school, continuing through two years of college at Wilberforce U. in Xenia, Ohio, before the finger pointed at him in 1953. It was only three months before entering the Army that he became interested in string bass and he began studying it seriously While in the service.

Coming out of the Army in 1955, he played with a number of small combos for the next year until the Sounds started. Simpkins names as his ideal bass men Ray Brown, Oscar Pettiford, Milt Hinton, Charlie Mingus, Paul Chambers and Doug Watkins.

Bill Dowdy is also a Benton Harbor product and was born August 15, 1933, in Benton Harbor, Mich. and became interested in drums in 1949. With Gene Harris and a bassist named Oleyer Jones a combo was formed, known as the Club 49 Trio; this group played a local radio show every Saturday and week end gigs in clubs. On graduating from high school Dowdy traveled with a band led by Rupert Harris, then went into the Army until 1954. After his discharge he went to live in Chicago.

"That was Where I did some valuable studying," he says. "I took lessons with a very fine drum teacher named Oliver Coleman at Roosevelt University. At that time I gigged around Chicago with blues bands, but also occasionally had a chance to work with jazz men like Johnny Griffin, Jay Jay Johnson and others who passed through town."

I was not surprised to learn of his preferences: they include Roy Haynes, Max Roach, Philly Joe Jones and Art Blakey as well as such more recent stars at Charlie Persip, Louis Hayes and Donald Bailey.

The most striking aspect of the Three Sounds is the remarkable integration of the unit. From the opening bars of Tenderly it is apparent that each man is listening sympathetically to his teammates. The crisp, sharp of Harris' touch and of Dowdy's cymbal work make on immediate and startling impact. I had immediate images of Dowdy spending months searching the Zildjian factory for exactly the quality he wanted on the cymbal. Whatever the circumstances were that to its acquisition, the timbre is extraordinary and the presence of all three men under Rudy van Gelder's watchful eye and ear is enhanced to maximum hi-fi effect.

Tenderly, with its Latin touches and ad lib single note piano lines, in indicates immediately that the group is beholden to no one combo For its inspiration; in fact, despite touches of Garner influence here and there, I could think of no trio, as such, that might hove influenced the Sounds in their overall concept.

Willow Weep For Me is a standard lends itself naturally to a funky treatment, since its main passage is based entirely on the principal notes of the blues scale. Notice how subtly Gene transforms the melody, instilling funk usually by the use of chords and making effective use of syncopation, especially in bars 3-4 and 7-8 of the release.

Both Sides is a blues that's about as basic as you can get, a simple three-note repeated phrase of pre-ragtime vintage appropriately accompanied by street-parade-style urging from Dowdy's sticks. But there is an immediate transition to a contemporary (though no less blue-rooted) concept as the ad lib passages begin. The 12-12-8-12 construction is employed.

Blue Bells is also a blues, slower in tempo and more varied in treatment, with Harris doubling on celeste, Its special interest is the introduction of Simpkins as a soloist. Here are all the virtues of the first-class modern bassist: a melodic solo feel, a sense of continuity that leads to a linear development rather than a mere series of disconnected two-bar breaks; and a Full, rich tone with faultless intonation. Harris, between passages, extends himself in a cruising, rhythmically chorded piano solo.

It's Nice is a Marcheta-like, pop-style melody whose phrases are dynamically underlined by a succession of insistent, exciting cymbal triplets. Both Harris and Dowdy excel on this track in their beautiful control of mood, of tempo-feel and of interplay; Simpkins, too, is heard briefly in a solo.

Goin' Home goes straight to the original home of jazz, the blues again, introduced on celeste this time. Simpkins' walking presence is a strong factor here as Gene wends his way from celeste to piano and back to celeste.

The Gillespie standard of the early 1940s, Woody'n You (originally named for Woody Herman but, ironically, never recorded by him) takes on Latinesque qualities in the first chorus but proceeds immediately to straight four at a bright-but-not-wild pace. Notice Gene's economical left hand punctuations against a funky right, the exciting exchange of ideas is the piano-drums fours that follow Simpkins' walking chorus; and the ingenious build of tension in Dowdy's lengthy drum workout.

O Sole Mio shows a sense of humor with its tongue-in-cheek alternation of the two traditional melodies (each sixteen bars long) with passages of Latinized blues. Naples was never like this.

The abiding impression left by this group's first album is that to intents and purposes, and very befittingly, they belie their name More than in anything else their success lies in the achievement not of three sounds but of a unity, a One Sound, from which a great deal more will soon be heard. To a list of discoveries that includes Jimmy Smith, Horace Silver, Art Blakey and a score of others now accepted as indispensable elements in the modern jazz scene, Alfred Lion can add another ascendant new name.

-LEONARD FEATHER

(Author of The Book of Jazz, Horizon Press)

Cover Photo by FRANCIS WOLFF

Cover Design by REID MILES

Recording by RUDY VAN GELDER