George Braith - Extension

Released - January 1967

Recording and Session Information

Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, March 27, 1964

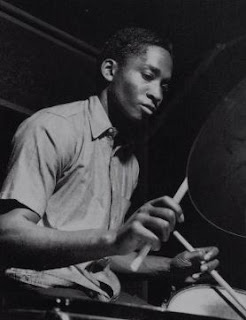

George Braith, tenor, soprano, alto sax; Billy Gardner, organ; Grant Green, guitar; Clarence Johnston, drums.

1325 tk.5 Nut City

1326 tk.10 Sweetville

1327 tk.14 Ethlyn's Love

1328 tk.15 Out Here

1329 tk.31 Extension

1330 tk.33 Ev'ry Time We Say Goodbye

Session Photos

Track Listing

| Side One | ||

| Title | Author | Recording Date |

| Nut City | George Braith | 27 March 1964 |

| Ethlyn's Love | George Braith | 27 March 1964 |

| Out Here | George Braith | 27 March 1964 |

| Side Two | ||

| Extension | George Braith | 27 March 1964 |

| Sweetville | George Braith | 27 March 1964 |

| Ev'ry Time We Say Goodbye | Cole Porter | 27 March 1964 |

Liner Notes

ORDINARILY, little anecdotes about what went on at a record session can get a little too cute for comfort (Charlie Parker was sitting in the control room because he once worked a weekend in Indianapolis with the bass player, and that sort of thing), but the quality of the mus!c on this album, combined with the circumstances in which it was made, makes it an exception.

To begin with, this is George Braith’s third LP as a leader for Blue Note. The first is called Two Souls In One (4148), the second Soul Stream (4161). On both of them, he plays more than one reed instrument at the same time, which tends to put one in mind of the volatile Roland Kirk, except that Leonard Feather, in his notes to Soul Stream, points out that Wilbur Sweatman used to play three clarinets at once. The idea is that it has to be more than a trick, it has to be musical. In essence, the practice of playing more than one instrument at the same time is an old music hall trick, and those who saw Carol Reed’s film about postwar Berlin, The Man Between, may remember the night club scene which featured a clown who played a number on two clarinets. So, the ability simply to do it is not the point.

Braith usually plays the stritch, or as he is more apt to call it, straight alto, which again puts one in mind of Kirk, but on this session he plays what he calls curved alto. The alto is not his, nor is the tenor he uses here, nor the soprano. His horns had been taken from his car the week before the session, and they’re not bock yet. The ones you hear are borrowed. I don’t want to go too deeply into that, and would, in fact, be willing to offer some kind of a prize to anyone who could come up with a complete list of record dates executed on borrowed horns, beginning with Charlie Parker’s famous King tenor, but it is difficult to play somebody else’s sax on short notice. And that is not all, ladies and gentlemen. Clarence Johnston, who sounds as though he had been playing with this group for years, appears here as drummer because Braith’s regular drummer had been taken ill.

So much for that. Those are the circumstances under which this LP was recorded, and they are highly unusual, but the music needs no apology, and I intend to make none for it. There is another aspect to this, though, which I find most fascinating. By any standards, Braith would be considered a contemporary musician. His style is his own, although one con hear, as can be heard in most saxophonists of his age, debts to Rollins and Coltrane —the most obvious remnants left are those Coltrane tenor flutters he employs now and again. And any reference to Kirk, of course, implies modernity. As a sort of general proposition, I would place Braith in the conservative wing of the avant-garde. But he has not chosen the sort of backing one would expect of such a musician. Organ, guitar and drums — that, with saxophone, is the standard lounge quartet. To followers of Blue Note LPs, the instrumentation will bring thoughts of Jimmy Smith, Stanley Turrentine, Lou Donaldson — another bag entirely. We all know the immense popularity that groups of this instrumentation have had over the past several years, and ¡t is almost as though Braith seeks to anchor his experiments in the broadest possible base.

I think the idea works. I am not sure that it was a conscious plan on Braith’s part, for he is at present working at a resort in upstate New York, and that is the kind of instrumentation most likely to be well received in such a place. But the effect is there, just the same, and deserves comment.

It is also worth noting, incidentally, that two of Braith’s three associates have appeared on his previous albums. The first of these is Grant Green, who has by now appeared on so many Blue Note LPs that it is pointless to reintroduce him. But I wonder if a certain tendency in jazz at the moment may not be attributable to Green and a few others like him. Sonny Rollins, Stan Getz and others, partly as a result of the popularity of the bossa nova, have added guitars to their groups. But as the tendency becomes more widely practiced, we see that it is the flat reverse of the way such things are usually done. Whereas a musical idea ordinarily starts out in a rarified atmosphere and only later becomes popular (Parker and Gillespie licks now show up on Frank Sinatra arrangements), the idea of sax and guitar started in the local clubs and only now has spread to units with wider critical acclaim. As I said, Green may be partly responsible.

Billy Gardner, a pianist whom Braith convinced to become an organist, has also appeared on the two previous LPs, and the lack of solemnity with which he takes his instrument is the cause of a refreshingly different sound this group gets. Gardner successfully avoids almost every practice and cliche that irritates the anti-organ faction. And I have explained earlier the circumstances under which drummer Clarence Johnston came to be present.

About the material: All except Cole Porter’s Ev’ry Time We Say Goodbye, which is played at on unusually fast tempo by tenor and alto, is the work of Braith, who seems, on this evidence, to be a composer with more than average promise. Nut City, played on tenor, was originally to be entitled Atlantic City, because that is where Braith had been working prior to this recording, and is where he wrote the piece. But certain of the more amusing aspects of that town induced him to change the name of the piece. Ethlyn’s Love, a gentle ballad played on soprano with a unique tone, is dedicated to Braith’s mother. Out Here is another way of saying “the scene,” and some of the harshness is a result of the loss of those instruments, the circumstance that inspired the piece. Extension, the title track, has a line played on soprano and tenor, and then tenor solos alone. Sweetville, in a more Coltranish mood, is also on soprano — it would seem that is the instrument Braith favors for ballads.

There is an unusual amount of variety on this LP, and no trickery at all. Basically, it doesn’t matter whether a man has one or eight horns in his mouth, it is all a matter of what kind of music he produces. The music of George Braith is of a very high order, and contains a good deal of happy excitement. When you hear what he has done, I think you will be eager to find out what he comes up with the next time out.

—JOE GOLDBERG