Sam Rivers - Involution

Released - 1975

Recording and Session Information

Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, March 7, 1966

Sam Rivers, tenor sax #1-3,5; Andrew Hill, piano; Walter Booker, bass; J.C. Moses, drums.

1708 tk.1 Violence

1709 tk.5 Hope

1710 tk.7 Illusion

1711 tk.10 Pain

1712 tk.16 Desire

1713 tk.19 Lust

Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, March 17, 1967

Donald Byrd, trumpet #1-4; Julian Priester, trombone #1-4; James Spaulding, alto sax, flute #1-5; Sam Rivers, tenor, soprano sax, flute; Cecil McBee, bass; Steve Ellington, drums.

1858 tk.10 Paean

1859 tk.20 Precis

1860 tk.25 Helix

1861 tk.32 Effusive Melange

1862 tk.33 Involution

1863 tk.34 Afflatus

See Also: BST 84261

Track Listing

| Side One | ||

| Title | Author | Recording Date |

| The Sam Rivers Sextet - Precis | Sam Rivers | March 17 1967 |

| The Sam Rivers Sextet - Paean | Sam Rivers | March 17 1967 |

| The Sam Rivers Sextet - Effusive Melange | Sam Rivers | March 17 1967 |

| Side Two | ||

| The Sam Rivers Sextet - Involutions | Sam Rivers | March 17 1967 |

| The Sam Rivers Sextet - Afflatus | Sam Rivers | March 17 1967 |

| The Sam Rivers Sextet - Helix | Sam Rivers | March 17 1967 |

| Side Three | ||

| The Andrew Hill Quartet - Violence | Andrew Hill | March 7 1966 |

| The Andrew Hill Quartet - Pain | Andrew Hill | March 7 1966 |

| The Andrew Hill Quartet - Illusion | Andrew Hill | March 7 1966 |

| Side Four | ||

| The Andrew Hill Quartet - Hope | Andrew Hill | March 7 1966 |

| The Andrew Hill Quartet - Lust | Andrew Hill | March 7 1966 |

| The Andrew Hill Quartet - Desire | Andrew Hill | March 7 1966 |

Liner Notes

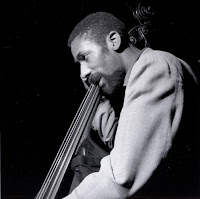

SAM RIVERS

Recognition has taken its time catching up with Sam Rivers. The reedman/composer/arranger has played the blues with Jimmy Witherspoon and T-Bone Walker, toured Japan with Miles Davis, worked for extended periods with Cecil Taylor and Andrew Hill, led groups of his own which ranged in size from trios to big bands. He was playing professionally in Boston during the early fifties, and during the mid-sixties Blue Note released his Fuschia Swing Song and Contours. Finally, in 1975, his Impulse trio albums (Streams, Hues) and a stunning big band Ip (Crystals) attracted the notice of the jazz public, and attention began to be paid. And now Michael Cuscuna has unearthed these sixties sessions from the Blue Note vaults, sessions which show that recognition could and should have come at that time. Rivers was already a reed virtuoso and an original composer/arranger, he was ready.

There is often a certain austerity to Rivers' music It isn't cold or forbidding, but it's more or less "pure," uncontaminated by programmatic conceits and atmospheric or romantic allusions. It is music that follows its own rules and exists on its own strictly musical terms, independent of the kind of extramusical imagery so often associated with organized sound. There is also a certain austerity to Rivers' determination to be original. "I worked out my own chord substitutions, wrote my own exercises to practice," he says "I listened to everyone I could hear to make sure I didn't sound like them. I wasn't taking any chances; I wanted to be sure I didn't sound like anyone else. I've gone to great lengths not to, so I'm slightly offended when people compare me to this player or that one. That means they aren't listening to me. A person doesn't have to sound like Charlie Parker or John Coltrane. It takes more work, but it can be done."

Originality is equally evident in his writing. "After about 1956 or '57 just about all the harmonies had been done the way they're being done today in the average jazz band," he says. "Around 1958-59 I did some compositions which were based on each instrument having a different solo part, all of which were harmonically together." By 1967 he was applying this linear compositional style to big band scores, working "more or less from clusters of sounds I want to hear at the time, and all I need really is silence and some paper." The style was not documented on record until the release of Crystals in 1975, or so everyone thought. In fact, the performances which make up the first two Sides of this album were waiting to be discovered. The six compositions are scored for only four horns and two rhythm instruments but Rivers makes the group sound much larger than it is.

Rivers did not develop his extraordinary abilities overnight. He has followed a deliberately paced growth pattern throughout his career, never making a step without scouting the territory where he was about to put his foot. He was born September 25, 1930 in Reno City, Oklahoma, making him a contemporary of Sonny Rollins and Ornette Coleman. His father, a graduate of Fisk University, was a veteran of the Fisk Jubilee Singers and the Silvertone Quartet. His mother had graduated from Howard. The two of them were "on the road," performing programs of spirituals around the country, when Sam came into the world. Some of the spirituals were from A Collection of Revival Hymns and Plantation Melodies by Sam's grandfather, Marshall W. Taylor, a book published in Cincinnati in 1882. "He was a minister and a musician, his two sisters were musicians, and both my parents were musicians and teachers. Everyone in the family plays, all my aunts, uncles, and cousins. Some are doctors and lawyers as well. It was something for everybody in a black family in the '30's to be college graduates; when I look back on it now, it was quite an achievement."

Sam's father was killed in an automobile accident in 1937 and his mother took a job at Shorter College in North Little Rock, Arkansas; Sam grew up around the campus. He'd already been exposed to the big bands of Cab Calloway and Count Basie and in Arkansas he heard Stravinsky and other advanced classical music around the house, in addition to black church music. Later, during the forties, he regularly stood outside night clubs and halls to listen to the musicians who were always passing through to play for Greater Little Rock's sizeable black community. He was rewarded with exposure to Coleman Hawkins, Lester Young, Buddy Tate, Don Byas, Earl Hines' big band, Andy Kirk, "One hard fact about the black community at that time" he says, "was that only a few people were recognized as being ethnically genuine. That would be the Baptist ministers and the jazz musicians. These were totally black originals: I could be a doctor, but a white doctor would probably be better because he had better training. The Baptist ministers and jazz musicians didn't really have white counterparts, and since I was already fascinated with the music, I gravitated to it." That meant taking up the trombone at age eleven and switching to tenor saxophone two years later.

Sam went to California as a Navy recruit and played his first professional job there with Jimmy Witherspoon. He also heard his first Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker records there. In 1947 he moved to Boston with his brother, bassist Martin Rivers. Sam started attending the Boston Conservatory and working with local bands; Boston was to be his home for almost twenty years, "because I was always working, seven nights a week, Boston was quite a good place for young musicians to go at that time. A lot of musicians had just come: Quincy Jones, Jaki Byard, Gigi Gryce, Dick Twardnk, Serge Chaloff, Joe Gordon. It was strange for me at times, going to school and gigging, the in-tune-ness of playing in a string quartet and the relaxation of playing in a jazz group. Bending notes and all that didn't happen in string quartets then. Anyway, I played in a band with Serge Chaloff (the legendary baritone saxophonist), Nat Pierce (later a pianist and arranger for Woody Herman), and several others. Then Jimmy Martin organized his big band. He wrote for us and so did Jaki Byard and Joe Gordon. I did an arrangement of 'All Too Soon' which really started my linear style of writing. It was a fifteen or sixteen piece band, and we played things like 'Billie's Bounce.' We'd play the head and then all the solos off the record in unison, and then go on to our own thing. Or we'd do twelve bars with everyone soloing collectively, or hit wrong notes at the end of the tunes. We were doing some of these things just because they were shocking to the older musicians. Actually, we were sort of the rage around Boston at that time."

Soon Sam had dropped out of school and was working in the intermission trio at a bar near "the theater where the shows and bands used to come in." Charlie Mariano and Quincy Jones would stop in during breaks. "I was playing a composite of Coleman Hawkins, Lester Young, Charlie Parker, and just about everyone else that I liked," he remembers, "and working on my own substitutions and exercises," During the mid-fifties he worked in Florida with another saxophonist, the R&B oriented Texan Don Wilkerson. There he played a short tour with Billie Holiday. Back in Boston in 1958, Rivers played with Herb Pomeroy's big band and led a quartet in a coffee shop near Harvard Square. One night in 1959 drummer Tony Williams, then thirteen years old, sat in and impressed everyone, During the early sixties there was work leading a pit band, backing up visiting shows featuring the likes of Wilson Pickett and Maxine Brown, In 1964, Rivers went on the road with blues guitarist T-Bone Walker. "T-Bone and all the other blues artists who hired me just wanted me to play the blues to the best of my ability," he says, "They weren't talking about stand up there and honk. They were talking about stand up there and play the horn."

In the middle of the tour with Walker, Rivers received a telegram from Tony Williams, who had moved to New York and worked briefly with Jackie McLean before being hired by Miles Davis. "Come to New York," the message began. "George (Coleman, Davis' tenor saxophonist) split. Miles wants you to join his group: Williams had played Davis tapes of the Rivers quartet from Harvard Square and the trumpeter had liked what he heard. Sam stayed with the Davis band, which also included Herbie Hancock and Ron Carter, for six months, touring Japan (where an extraordinary live album was recorded and released on Japanese CBS) and the U.S. "Miles was still doing things that were pretty straight," he recalls. "I was there, but I was somewhere else too. I guess it sounds funny, but was already ahead of that I kept stretching out and playing really long solos, and that's probably why I didn't last. We recorded an album in Japan and then when we got back to New York, Miles got Wayne Shorter."

At this point, Rivers' music begins to be documented. Williams' Blue Note lp Spring, recorded in August, 1965, features Rivers and Shorter playing side by side and is particularly revealing. Sam's playing is fluid and mutable, full of complicating phrases with quick little denouements, globular smoothnesses contrasted with gruff overtone effects, asymmetrical note groupings, unusual scalar ideas, unexpected uses of silence. It is also somewhat diffuse. Shorter's sound is more unvarying and his ideas, less multitudinous than Rivers', flow more smoothly. Nevertheless, it is Rivers' challenging, encyclopedic solo on "Love Song" which lingers in the mind as the album's high point.

The saxophonist's own Blue Note albums followed. Fuschia Swing Song, with familiar associates Byard, Williams, and Ron Carter, stands as the definitive statement of the mid-sixties Boston progressives. The chord progressions and voicings studiously avoid cliche, improvisational structures segue from chord cycles to free form and back in the course of single compositions, and the leader's playing refers to a lengthy history which encompasses blues, the classic tenors and bebop. The modal structures then being popularized by John Coltrane are notably absent from the date. "I was never particularly into that," Rivers explains. "In most cases so-called modal jazz wasn't really modal at all. People were playing free over the top of modes or, more often. just staying in one key. Now really playing in a mode would be limiting yourself to the eight or so notes in that mode, period. That's the way I teach modes, I guess I'm a kind of purist in that I don't believe you should say you're doing one thing when you're doing something else."

After the Miles Davis experience Rivers worked with pianist Andrew Hill, and it is from this period that the third and fourth sides of this album derive. They were recorded under Hill's leadership in March, 1966, and never released. Perhaps the titles offer a clue to the company's decision not to issue them: "Violence." "Pain," and "Illusion" are hardly typical ideas for compositions, and the music itself is intriguing but almost unremittingly sombre. Even the rhythmic Latin montuno figure Hill uses in "Illusion" conveys an almost desperate sadness. The pieces on the second side are more cheerful, especially the lovely "Hope." In all, this was a uniquely involving album, one about which Hill must have cared a great deal. The pianist was experiencing an extremely frustrating struggle for economic self-sufficiency at the time and his turbulent music reflected it. But echoes of his childhood in Haiti and the use of extremely dense harmonic textures were also prominent.

Rivers' solo work on "Violence" is a spitting, roaring evocation of the title. There's a captivating, tension-filled piano-tenor duet on "Illusion," another strong tenor solo, and the best J. C. Moses drum solo on record. On "Hope" the saxophonist is breathy and delicate; he again demonstrates how attuned he was to Hill's compositional goals on "Desire" with a solo which seems to strive for, but never achieve, rest or satiation. "Pain" and "Lust" are superb trio performances, the first swinging and rather Monk-like, the second light and shimmering. Walter Booker is an unusually strong supporter and soloist throughout. There are few moments of lyricism as it's commonly understood but, like many of the jazzmen who matured during the sixties, Hill was after a redefiniton of feelings like "pretty," a new and more inclusive standard of beauty. There is a nobility to much of the music here, a determination to transmute life's roughest blows into affirmative artistic statements that's aided immeasurably by Rivers' imagination and strength.

The sextet heard on sides one and two recorded in March, 1967 under Rivers' direction. It's a kind of all-star group, though the rhythm section was intimately familiar with Rivers' music. Drummer Steve Ellington had been particularly close to the saxophonist for some time, and in fact the two of them had recorded tapes earlier in the decade which Rivers remembers as some of the most advanced playing he ever did. The prodigiously swift and solid bassist Cecil McBee was only beginning to build his reputation: his landmark bass solos with Pharoah Sanders were several years in the future. Donald Byrd and Julian Priester must have seemed strange choices for a date as conceptually "free" as this one, since they were associated with more "inside" playing, but Priester had worked in Sun Ra's earliest bands and Byrd frequently played with some of the younger musicians who were revamping jazz time and techniques, though not on records. Alto saxophonist James Spaulding was a kind of Blue Note regular at the time. He had been associated with Charles Tolliver and Bobby Hutcherson and his direction was basically neo-bop, with free form leanings.

Rivers probably chose each player for this combination of adventurousness and grounding in tradition; he was never one to advocate total freedom at the expense of musicality and roots. "The sixties was a heck of a period," he says. "A lot of traditional musicians went right through the period and didn't get anything out of it. And a lot of avant-garde musicians were wasting their time just playing the music of the sixties and ignoring the music of the fifties and forties." The six compositions heard on sides one and two aren't easily categorized in terms of stylistic decades. The loosely splashing swing of the piano-less rhythm section is more conservative than the work of, say, Sunny Murray and Alan Silva, but it's considerably freer than bebop. Rivers' scoring for the horns is almost uniformly dense but his remarkable ear for color and the personal sounds of the players result in a parade of marvellously sensual and ever-changing colors. Rarely has atonality in jazz writing sounded this warm. The solos are as varied as the diverse styles of the musicians and Byrd and Priester in particular reach for continuites and effects not even hinted at on their other recordings from the same period.

Spaulding has the bright opening solo on "Precis." Byrd then permutates a series of intervals from the theme, demonstrating his grasp of the new music's improvisational procedures and producing, with his broken tones and various speech-like attacks, a kind of polytonal funk. Rivers follows on tenor. "Paean" has a smooth, almost slippery Priester statement, a great flying pizzicato workout by McBee, and then Rivers on soprano. The saxophonist swings hard and then begins loosening and tightening the time, producing an elastic resilience. Back on tenor in "Effusive Melange" he sputters and tears into long held chords in an exemplary display of his control of harmonics. Priester joins in before the fade out.

"Involution" is scored for two flutes, played by Rivers and Spaulding, and rhythm. The first fluke solo sounds like Sam. who's identifiable in the improvised ensembles by his more mercurial, wider-ranging playing: Steve Ellington's drum solo produces a wide open sound, with high cymbals ringing and low tom toms underneath. "Afflatus" is a slow, reflective number, a kind of tenor incantation which Rivers elaborates into some forceful overtone playing and, after McBee switches from bowing to plucking for his solo, a faster but still deliberate rethinking of the theme. This trio performance, with its free-flowing time and broad tenor sound, is more reminiscent of Albert Ayler's work than anything in Rivers' later recordings. There's a Moorish-flavored ending. "Helix" closes the album in an optimistic mood. Byrd has a bright, strutting solo and Spaulding sails in with a tone reminiscent of Eric Dolphy's and a sense of line not unlike the late Booker Ervin's. Rivers soars on tenor over jabbing punctuations from the other horns.

In the years following the recording of this material the saxophonist worked with pianist Cecil Taylor — he appears on Taylor's Nuits de la Foundation Maeght series on Shandar — and on his own projects, aside from a brief but very memorable stint with a McCoy Tyner quintet that also featured trumpeter Woody Shaw. In 1970 he opened Studio Rivbea, on Bond Street in lower Manhattan, in partnership with his wife Bea. They've been married, he notes proudly, for 27 years. The studio, a basement loft with comfortably informal seating, has become a place where exciting new music is heard consistently. Dewey Redman, Frank Lowe, Charles Tyler and other avant-gardists appear there with their groups, but so do more traditionally oriented players like Clifford Jordan and Sonny Fortune. Sam rehearses his trios, medium-sized groups and big bands in the space. He's also found time during the past few years to work as composer-in-residence with the Harlem Opera Society and perform and teach as an artist-in-residence at Wesleyan University.

The tall, lean saxophonist with the high forehead, creased brow, and penetrating eyes continues to make singular music. "The way I see it," he says, "the music of the Seventies should be a fusion of the Forties, Fifties and Sixties." That's as good a description as any of the sounds in this package, though the listener will be tempted to add that the warmth, wit and intelligence of those decades, as well as their styles, are evident throughout.

ROBERT PALMER