Hank Mobley - Curtain Call

Van Gelder Studio, Hackensack, NJ, August 18, 1957

Kenny Dorham, trumpet #1-5; Hank Mobley, tenor sax; Sonny Clark, piano; Jimmy Rowser, bass; Art Taylor, drums.

tk.3 My Reverie

tk.6 Curtain Call

tk.9 On The Bright Side

tk.10 The Mobe

tk.11 Don't Get Too Hip

tk.12 Deep In A Dream

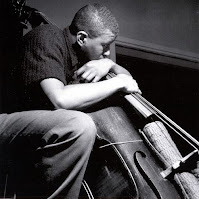

Session Photos

|

| CD Cover - See Also BLP 1550 |

Photos: Francis Wolff/Mosaic Images /

https://www.mosaicrecordsimages.com/

Track Listing

| Side One | ||

| Title | Author | Recording Date |

| Don't Get Too Hip | Hank Mobley | August 18 1957 |

| Curtain Call | Hank Mobley | August 18 1957 |

| Deep In A Dream | Delange-Van Heusen | August 18 1957 |

| Side Two | ||

| The Mobe | Hank Mobley | August 18 1957 |

| My Reverie | Debussy-Cliaron | August 18 1957 |

| On The Bright Side | Hank Mobley | August 18 1957 |

Liner Notes

Hank Mobley started showing up on Blue Note sessions in 1954. By 1955, he had made his first album as a leader (a 10" lp) and was a member of the Jazz Messengers. He was prolific as a leader and sideman for Blue Note right up to 1971. But never was he so everpresent as during the 1500 series. He was on sessions by the Jazz Messengers, Horace Silver, Kenny Burrell, Curtis Fuller, Sonny Clark, Johnny Griffin, Kenny Dorham, Lee Morgan, J.J. Johnson and Jimmy Smith as well as producing 6 issued albums under his own leadership. There were two more Mobley dates from this period: POPPIN' which was issued in the seventies and CURTAIN CALL released here for the first time.

Mobley has never received the recognition that he deserves. It is fortunate that Blue Note stayed with him for so many years, capturing one beautiful album after another. Part of the reason for his lack of popularity was his tone, softer than most of the hard boppers. Also his sense of solo construction is a complex, inventive marvel that can slip by the casual listener. He was never an audience grabber, but he could seduce one if given the chance.

This album brings him together with his old Jazz Messenger hornmate Kenny Dorham. And it is among KD's finest playing of the period. KD and Mobley were also in Max Roach's band at this time.

The rhythm section consists of Blue Note regulars Sonny Clark and Art Taylor with George Joyner (now Jamil Nasser) on bass. This same rhythm section propelled the Lou Donaldson Sextet four months later on LOU TAKES OFF (BLP 1591).

Nasser was born in Memphis in 1932 and raised with piano wizard Phineas Newborn. An early practitioner of the electric bass, he toured with B.B. King in the mid fifties, finally settling in New York in 1956 where he freelanced with Gene Ammons, Red Garland and many others. His prime recognition comes from the years he spent in the sixties and seventies with Ahmad Jamal's trio.

Except for two standards, all the compositions here are Mobley's. Don't Get Too Hip is a sly, easy 12 bar blues line, repeated twice. Sonny Clark plays a lovely intro and then glides in and around the melody as stated by the horns. He has the first solo, running through a range of attitudes. His first chorus is sparse and tasty, his second more playful, the third in a be-bop mode and the fourth evolving into funk. To add to the dynamics of the tune, Clark lays out for the first 24 bars of the trumpet and tenor solos. Dorham's solo is gorgeous and soulful with squeezed notes, bent tones and great thoughtful ideas. Hank's sound here foreshadows the smooth, round, soft tone of his 1960—61 period. His solo too is rich in beauty and well-thought out ideas. After a brief bass solo, the ensemble returns for a repeat of the theme, which is admittedly hesitant in spots.

Curtain Call, a fast 32 bar AABA melody on standard changes offers some wonderful playing. Mobley is sleek and swift and smooth like a jungle cat. KD is assured and cooking, applying his boppish roots with his own personal stamp. Clark is clean and sparkling. Even the tenor, drum, trumpet trading of four bar phrases has a seamless coherence to it.

Deep In A Dream is set up by Clark for beautiful tenor and piano solos. Dorham lays out here. This lovely lyrical performance makes for interesting comparison to Clark's 1961 quartet recording with Ike Quebec on tenor.

The Mobe, a medium up AABA tune with a hint of Dameronia. The bridge is played in Latin rhythm on the theme, but not on the solos. Mobley's solo is deceptively relaxed as it climbs in construction with ever moving lines. KD takes a nice warm approach to his solo, while Clark simply shimmers with clarity. The tenor-trumpet 8 bar exchanges are very effective.

Debussey's My Reverie is taken at a surprisingly bright tempo with the trumpet stating the melody. Dorham also takes the first solo with an arresting directness and intimacy; his control of the horn's air flow is hypnotic. Clark and Mobley turn in fine solos before KD steals the show again with a reading of the melody that is a solo unto itself. Mobley gracefully plays obbligato behind him.

On The Bright Side is a light, uptempo 32 bar AABA piece. This is a happy, straight ahead affair with spirited solos. Clark cleverly ends his solo with pieces of the theme. The solo sequence ends the tenor and trumpet trading fours with Taylor.

What is most striking about the 8 albums that Mobley led between November of 1956 and February of 1958 is the incredible variety in personnel, instrumentation and material. And there is not an unsuccessful session among them. He would re-emerge in 1960 and '61 with four masterful album of consumate creativity and then countless albums from 1963 to 1971 with a hard sound, but the same incredible imagination. The common thread throughout is beauty and intelligence.

—MICHAEL CUSCUNA

Original Session Produced by ALFRED LION

Recording by RUDY VAN GELDER