Kenny Dorham - Afro-Cuban

Released - March 1957

Recording and Session Information

Van Gelder Studio, Hackensack, NJ, January 30, 1955

Kenny Dorham, trumpet; Hank Mobley, tenor sax; Cecil Payne, baritone sax; Horace Silver, piano; Percy Heath, bass; Art Blakey, drums.

tk.2 Venetia's Dance

tk.6 K.D.'s Motion

tk.12 The Villa

Van Gelder Studio, Hackensack, NJ, March 29, 1955

Kenny Dorham, trumpet; Jay Jay Johnson, trombone; Hank Mobley, tenor sax; Cecil Payne, baritone sax; Horace Silver, piano; Oscar Pettiford, bass; Art Blakey, drums; Carlos "Patato" Valdes, congas; Richie Goldberg, cowbell #1,3.

tk.3 Minor's Holiday

tk.5 Basheer's Dream

tk.7 Afrodisia

tk.8 Lotus Flower

See Also: BLP 5065

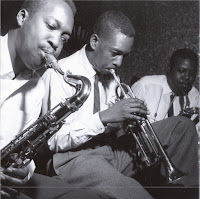

Session Photos

Photos: Francis Wolff

Track Listing

| Side One | ||

| Title | Author | Recording Date |

| Afrodisia | Kenny Dorham | 29/03/1955 |

| Lotus Flower | Kenny Dorham | 29/03/1955 |

| Minor's Holiday | Kenny Dorham | 29/03/1955 |

| Basheer's Dream | Gigi Gryce | 29/03/1955 |

| Side Two | ||

| K.D.'s Motion | Kenny Dorham | 30/01/1955 |

| La Villa | Kenny Dorham | 30/01/1955 |

| Venita's Dance | Kenny Dorham | 30/01/1955 |

Credits

| Cover Photo: | FRANCIS WOLFF |

| Cover Design: | REID MILES |

| Engineer: | RUDY VAN GELDER |

| Producer: | ALFRED LION |

| Liner Notes: | LEONARD FEATHER |

Liner Notes

THE contents of this LP provide a revealing dual portrait of Kenny Dorham. One side of him, the one with the Afro-Cuban leanings, can be observed in the first four tunes, featuring an eight-piece band, previously released on a 10” LP. The other side, both of Kenny and of the record, can be observed in the last three tunes, which were recorded with a quintet and have never previously been released.

It has taken McKinley Howard Dorham quite a few years to earn the recognition that should have been his during the middle 1940s. For a long time, during the halycon era of the bop movement, Kenny was Mr. Available for every trumpet choir in every band and combo. If Dizzy wasn’t around and Howard McGhee was out of town, there was always Kenny. And so it went from about 1945 to ‘51, always in the shadow of those who had been first to establish themselves in the vanguard of the new jazz.

Slowly, in the past few years, Kenny has emerged from behind this bop bushel to show the individual qualities that were ultimately to mark him for independent honors. Numerous chores as a sideman on record dates for various small companies led to his inclusion in the important Horace Silver Quintet dates for Blue Note (BLP 1518), and, as a result of his fine work on these occasions, to the signing of a Blue Note contract and his first date for this label as a combo leader on his own.

If the Kenny Dorham Story were ever made into a movie (and the way things are going in Hollywood at the moment, don’t let anything surprise you) it would begin on a ranch near Fairfeld, Texas on August 30, 1924. The actor playing Kenny as a child would be shown listening to his mother and sister playing the piano and his father strumming blues on the guitar.

Then there would be the high school scenes in Austin, Texas, with Kenny taking up piano and trumpet but spending much of his time on the school boxing team; and later the sojourn at Wiley College, where he played in the band with Wild Bill Davis as well as majoring in chemistry. In his spare time Kenny would be seen making his first stabs at composing and arranging.

After almost a year in the Army (during which his pugilistic prowess came to the fore on the Army boxing team) Kenny went back to Texas, joining Russell Jacquet’s band in Houston late in 1943 and spending much of 1944 with the band of Frank Humphries.

From 1945 to ‘48 Kenny was on the road with several big bands, including those of Dizzy Gillespie, Billy Eckstine, Lionel Hampton and Mercer Ellington in that order. Then he spent the best part of two years playing clubs as part of the Charlie Parker Quintet, lurking on the edge of the limelight occupied by the immortal Bird, he began to lure a little individual attention as something more than the section man and occasional soloist he had been for so long. One of his important breaks was a trip to Paris with Bird in 1949 to take part in the Jazz Festival.

Settling permanently in New York, Kenny become a freelance musician whose services alongside such notabilities as Bud Powell, Sonny Stitt, Thelonious Monk and Mary Lou Williams gradually impressed his name and style on jazz audiences.

During 1954-5 Kenny worked most frequently around the east with a combo that constitutes the nucleus of the outfit heard on these sides — Hank Mobley. Horace Silver and Art Blakey.

Mobley is on Eastman, Ga. product, born there in 1930 but raised in New Jersey. Making his start with Paul Gayten in 1950. he rose to prominence with Max Roach’s combos off and on from 1951-53 and with Dizzy in ‘54.

Mobley as well as Silver and Blakey ore of course familiar figures at Blue Note, abundantly represented in the catalogue through their sessions with the Jazz Messengers (1507, 1508, 1518). Horace and Art are also on such other sessions as the Horace Silver trio (BLP 1520) and A Night at Birdland (BLP 1521, BLP 1522).

Jay Jay Johnson, whose eminence was saluted on BLP 1505 and BLP 1506, was recently elected the “Greatest Ever” by a jury of 100 of his peers in the Encyclopedia Yearbook of Jazz “Musicians’ Musicians” poll.

Cecil McKenzie Payne, a baritone sax man with a long and distinguished record in modern jazz circles, is a 34-year-old Brooklynite whose career as a bopper began right after his release from the Army in 1946 and took him through the U.S. and Europe with Dizzy Gillespie until ‘49. when he began free-lancing in New York with Todd Dameron, James Moody and Illinois Jacquet.

Carlos “Potato” Valdes, the conga drummer, came over from Cuba a couple of years ago. It was Gillespie who first told Kenny Dorham about him and “little Benny” Harris who dug him up and brought him to Kenny’s rehearsal. “He gassed them all,” recalls Alfred Lion succinctly.

Completing the octet, Oscar Pettiford provides the indomitable bass sound that won him the Esquire Gold Award in 1944 and ‘45 and the Down Beat Critics’ poll in 1953.

For the four tunes with the Afro-Cuban rhythm motif, Kenny says, “I tried to write everything so that the rhythm would be useful throughout and would never get in the way.” As o consequence, the Cuban touch sounds as if it is a part of the whole, rather than something that has been superimposed on a jazz scene, as is sometimes the case.

Afrodisia is a title that has been used before, but this is a new composition. The theme and interpretation recall somewhat the Gillespie approach to material of this type. like the patriot who is plus royaliste que le roi, Kenny and his cohorts achieve a more interesting and more Cuban atmosphere here than you will hear on many performances emanating direct from Havana. The “Potato” is really cooking on this one.

Lotus Flower, after Horace’s attractive intro, shows how the Cuban percussion idea can be applied effectively to a slow, pretty melody. Jay Jay’s solo, though short, has a melancholy quality that complements the mood set by Kenny’s delicately phrased work here.

Minor’s Holiday didn’t get that title only because of its minor key; it was also named for Minor Robinson, a trumpet player in New Haven. A mood-setting rising phrase characterizes the opening chorus, leading into a loosely swinging, pinpoint-toned trumpet solo that shows, like all his work on this date, the high degree of individuality Kenny has achieved. Mobley and Jay Jay also have superior solos.

The session ends with an original commissioned by Kenny from Gigi Gryce, the talented ex-Hampton reedman. Basheer’s Dream has a minor mood of singular intensity sustained by Kenny, Hank and Jay Jay, with Valdes and Blakey allied as a potent percussion team and Horace, the Connecticut Cuban, contributing some discreet punctuations.

The reverse side features four of the principal protagonists from the Afro-Cuban dote — Dorham, Mobley, Payne and Blakey with Percy Heath of Modern Jazz Quartet fame replacing Pettiford. The session opens with K. D.’s Motion, a medium-paced blues, partly in unison and partly voiced. After an eight-measure bridge, Kenny dives into four choruses of fluent ad-libbing. The blues being at once the lowest and highest common denominator of all true jazzmen, Kenny is greatly at ease here, the solo offering a first-rate sample of his ideation and continuity. Payne, Mobley and Silver also cook freely before the theme returns at the end of this effective five-minute exploration of the 12-bar tradition.

The Villa, another Dorham original like all the music on these sides, is o melodic theme that could make a good pop song, though at this fast tempo it serves as o fine framework for trumpet, tenor and baritone solos, with Horace comping enthusiastically like a coach urging his team on from the sidelines. Kenny and Art trade fours for 24 measures before the ensemble returns.

Venita’s Dance is a rhythmic yet somehow reflective and wistful theme, taken at a medium pace. Kenny’s solo, constructed mostly in downward phrases. maintains the mood established in the opening chorus, after which Mobley’s virile, assertive tone and style are in evidence, followed by excellent samples of Payne and Silver.

Whichever side of Kenny Dorham intrigues you most, whether you dig him particularly as composer or trumpeter, Afro-Cuban specialist or mainstream jazzman, most of what you will hear on this disc will offer a high protein diet of musical satisfaction.

— Leonard Feather

RVG CD Reissue Liner Notes

A NEW LOOK AT AFRO-CUBAN

This collection represents the first flowering of Kenny Dorham as a significant trumpet stylist and composer. As Leonard Feather points out in his original liner notes, it was a long time in coming. Despite a recording career of more than nine years when the first of the present sessions was taped, Dorham previously had been featured only once as a leader, on a 1953 session for Debut. Like many of his East Coast contemporaries, Dorham had also suffered through the economic downturn jazz experienced during the early-1950s. After his two-year stint with Charlie Parker ended in 1950, he had only made a handful of sideman appearances on record, though always in the employ of such important leaders as Thelonious Monk, Sonny Rollins, and Lou Donaldson.

Things began looking up in November 1954, when Dorham participated in a session under Horace Silver’s name that turned out to be the debut of the Jazz Messengers cooperative. A Blue Note contract followed, with the sextet date here intended as his leader’s debut on the label; but other music, and changes in technology, intervened. The second Silver/Jazz Messengers session, featuring the hit “The Preacher,” was made a week later, followed by the Dorham octet date in late March, all as the 10” LP format (for which each of these sessions was designed) was in the process of being phased out in favor of the lengthier 12” disc. Given the exceptional nature of the Afro-Cuban octet, Blue Note chose to release that music first, which explains why the earlier Dorham date was held back for a year, only to appear with one of its four tracks omitted for reasons of space.

While lacking the soulful appeal of Silver’s music, the sextet tracks are still excellent examples of the emerging hard bop style that Dorham did so much to establish. They find the trumpeter in highly compatible company, with three of his fellow Jazz Messengers plus Percy Heath (who had been heard with Dorham on Debut) in place of bassist Doug Watkins, and Cecil Payne’s horn adding bottom. The trumpeter and baritone player would reunite on several significant occasions over the next 15 years, including Payne’s’ first LP as a leader in 1956, Dorham’s 1959 Riverside album Blue Spring(where the beautiful “Venita’s Dance” reappeared under the title “Passion Spring”), and on the circa-1970 Payne album Zodiac that turned out to be Dorham’s final visit to a recording studio. The playing on the four sextet tracks is strong, yet the most impressive aspect of the session is Dorham’s writing. “La Villa” became something of a jazz standard after Dorham revisited it two years later on his Riverside disc Jazz Contrasts. The session’s bonus track, which sounds like an a cousin of Sonny Rollins’s “Paradox,” was given the title “K. D.’s Cab Ride” upon its initial release in the 1980s, a reference to Dorham’s ability to sketch out new tunes on the way to recording sessions. It later was discovered that Dorham had given the tune the title “Echo of Spring” (not to be confused with Willie “The Lion” Smith’s “Echoes of Spring”).

The octet date that followed two months later is one of the definitive sessions of the era, and an important contribution from the jazz side in the development of the “Latin jazz” aesthetic. Among its important features are the introduction of Carlos “Patato” (not “Potato,” as the original credits had it) Valdes to the jazz world, the volcanic pairing of Valdes and Art Blakey (harkening back to the Blakey/Chano Pozo tandem on James Moody’s 1948 Modernists session for Blue Note), the exceptional collection of featured horn soloists (including J. J. Johnson, who had featured Dorham on his own 1949 New Jazz debut), and more compelling compositions and arrangements from Dorham. “Minor’s Holiday” became the best known of the three Dorham originals, thanks in part to the exceptional subsequent version by the Messengers on their Café Bohemia session the following November. The coda Dorham employs here was turned into the new, non-Afro-Cuban original “Monaco,” which Dorham featured on his own Bohemia date in May of 1956.

All of the soloists are consistently excellent here, which must have made it difficult for producer Alfred Lion to select between the original master and the alternate take of “Minor’s Holiday.” Session logs reveal that the alternate, which was recorded first, was in fact considered as being equal to the master. Could the clincher have been Hank Mobley’s allusion near the end of his solo on the master to “RockaBye Basie?” In any case, the citation remains among this listener’s favorite moments in jazz quotology.

— Bob Blumenthal, 2007

No comments:

Post a Comment