Horace Silver - Further Explorations

Released - March 1958

Recording and Session Information

Van Gelder Studio, Hackensack, NJ, January 13, 1958

Art Farmer, trumpet #1,3-6; Clifford Jordan, tenor sax #1,3-6; Horace Silver, piano; Teddy Kotick, bass; Louis Hayes, drums.

tk.3 The Outlaw

tk.9 Melancholy Mood

tk.10 Moonrays

tk.12 Ill Wind

tk.16 Pyramid

tk.21 Safari

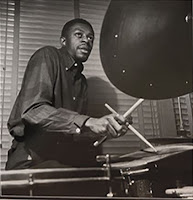

Session Photos

Track Listing

| Side One | ||

| Title | Author | Recording Date |

| The Outlaw | Horace Silver | 13/01/1958 |

| Melancholy Mood | Horace Silver | 13/01/1958 |

| Pyramid | Horace Silver | 13/01/1958 |

| Side Two | ||

| Moon Rays | Horace Silver | 13/01/1958 |

| Safari | Horace Silver | 13/01/1958 |

| Ill Wind | Harold Arlen, Ted Koehler | 13/01/1958 |

Credits

| Cover Photo: | FRANCIS WOLFF |

| Cover Design: | |

| Engineer: | RUDY VAN GELDER |

| Producer: | ALFRED LION |

| Liner Notes: | LEONARD FEATHER |

Liner Notes

THE EXPLORER in jazz is faced with alternating problems. If his reputation hos been gained through the establishment of new orchestral, instrumental or tonal horizons, he may feel free to explore horizontally — to reach out into new areas of composition and interpretation — without fear of losing any substantial segment of the group of camp-followers that constitutes his public. If, on the other hand, his success has been brought about largely on the strength of a highly personal solo style then his explorations must be made vertically: that is, he must dig deeper and discover valuable new geological specimens within his own self-imposed territory.

Horace Silver belongs in the second category. If he were to branch out into the fields of polytonality or atonality, if his latest LP were the end-product of a series of experiments with the twelve-tone scale, one can safely assume that he would alienate the bulk of the true Horace Silver fans who respect him for what he is — a straight-down-the-line. tonal swinger, functioning continuously, and with consistent success within the orbit of the small, bop-derived jazz ensemble.

Aware of his place in the development of jazz, and conscious of his need to avoid settling in a rut, Horace has reconciled he need for retention of the qualities that brought him his reputation with the no less pressing need for new compositional concepts tailored to his style and setting. On these new sides there is an admirable blend of the old and familiar attributes of the Silver Quintet (and its related predecessors such as the Art Blakey group from which it stemmed) with a tendency toward experimentation in terms of construction.

The Outlaw, for example, is based on a twice-played thirteen-bar line, leading into what might be called a channel for ten bars, a sixteen-bar vamp, and a two-bar break, catapulting Cliff Jordan into the first of a series of ad lib solos. The use, but with discreet limitations, of Latin rhythm, and the conscious but never self-conscious departure from the conventional 32 and twelve-bar forms, may not seem to have much more than mathematical interest (Latin rhythms are, after all, still mere methods of dividing the eight eighth notes in a bar, and even a 13-bar phrase has the usual four beats to each bar), but the overall effect, especially in context with less heterodox forms as heord on o couple of the other tracks, helps to bring to the record a sense of balance that it might otherwise lack.

Melancholy Mood offers a no less piquant defiance of symmetrical convention. "It's kind of mysterious, I guess,” offers Horace, "two seven-bar phrases followed by a seven-bar channel — in other words, a ballad based entirely on seven-bar phrases. The first chorus is just me with Teddy bowing, then I blow some on it in the second chows and we go back to the mood of the beginning.”

Pyramid, not related to o similarly titled old Ellington composition, is o minor-mode unison line to which the rhythm section’s sharp punctuations lend much of its character. The construction here is more conventional, but again there is on intermittent use of Latin rhythm, during the channels. Art Farmer, who takes the first solo, seems particularly well equipped to flex his ideas on these exotic, quasi-Asiatic themes.

Moon Rays is what Horace calls “a sort of walking balled — a little faster than the typical ballad.” There is an ingenious use here of the two-part harmony offered by the group’s two horns, with pedal-point rhythm effects on the dominant. Horace's solo is particularly, if we may use a word that is rapidly being driven into the ground, funky. “Do you notice what the drums played in there?", says Horace. “Have you ever dug Tito Puente or Machito when they play a ballad — that little tick-tick-tick-tick thing that they keep going on the timbales? I don’t know what you call it, but it’s a special Latin effect and we thought it would fit this number."

Safari is a minor bop line written by Horace some eight or nine years ago, long before he came to New York. It's played here at a tempo so agitated that only Sonny Rollins would call it slow. Cliff Jordan, standing out among a generally exciting sequence of solos, cooks up a banquet on this, and Louis Hayes also has a brief solo workout.

Harold Arlen’s standard of the early 1930's, Ill Wind, is swung moderoto with Hayes’ doubled rhythm lending added pulsation during the piano solo. The group that plays these six sensitively integrated performances has been intact for many months; in fact, during almost two years as a leader, Horace hos rarely had occasion to change men. Art Farmer has been with him right from the start, though Donald Byrd took over the chair for a short period. Louis Hayes. too, hos been o member almost from the combo’s inception in the late summer of 1956. “He’s always been great,” observes Horace, “but now he senses every nuance of the group and he’s playing with more polish, more taste than ever.”

Cliff Jordan joined Horace in the summer of 1957 on what was in effect a trade with Max Roach, as Max took over Horace’s previous tenor man, Hank Mobley. Teddy Kotick has been one of the five pieces of Silver for better than a year, replacing the original bassist Doug Watkins.

The group as you can hear it on these sides played an engagement at Birdland in February of 1958. Those of us who hod followed Horace with interest from the first tentative months in New York with Stan Getz in 1950, from the earliest LPs for Blue Note a couple of years later, were encouraged not only by the firmly meshed performance of the group, but by the exceptionally sanguine reaction of a large and vociferous audience. It hos token Horace a little while to break through, but the next year should see his group firmly entrenched as one of the most dependable conveyor belts for the brand of jazz he typifies. The explorations of the Silver Quintet ore now ready to expand to any section of the United States, or any other territory, from pole to pole, where silver is recognized as legal tender.

—LEONARD FEATHER

(Author of The Book of Jazz, Horizon Press Inc.)

Cover Photo by FRANCIS WOLFF

Recording by RUDY VAN GELDER

RVG CD Reissue Liner Notes

A NEW LOOK AT FURTHER EXPLORATIONS BY THE HORACE SILVER QUINTET

While it is hard to conceive of any Horace Silver album from his Blue Note prime as overlooked, Further Explorations qualifies. It was the last of Silver's works from the decade of the 1950s to appear on compact disc; and when it finally did, in 1997, it was part of the limited-edition Connoisseur series. A single listen should convince that, based on the quality of both the writing and the performances, the album is a typically excellent effort. Why, then, does it remain less celebrated than its companions of the period?

One reason may be the front-line personnel. While earlier Silver efforts included Donald Byrd and/or Hank Mobley, the fellow Jazz Messenger alums who helped the pianist launch his career as a working bandleader, and subsequent titles were enhanced by the ultimate Silver horn tandem of Blue Mitchell and Junior Cook, the present lineup of Art Farmer and Clifford Jordan appears transitional. Appearances can deceive, however, especially in the case of Farmer, who was heard on the May 1957 The Stylings of Silver and would have appeared on the November 1956 Six Pieces of Silver as well but for the restrictions of his short-lived contract with ABC Paramount. The Farmer/Silver connection actually extends back to 1954, when Farmer featured his future boss on three Prestige sessions; and the January '57 Hank Mobley session with Farmer, Silver, Doug Watkins, and Art Blakey can be either a Messengers reunion with Farmer as a ringer or a Silver Quintet date with Blakey in place of Louis Hayes. In sum, Farmer knew Silver's playing and writing intimately, and on this last recorded meeting of the pair proves to be an exceptional interpreter.

Clifford Jordan was a more fleeting presence in the Silver band. His tenure lasted less than a year, with the present tracks serving as the only documentation of his service. (Silver did back up Jordan and John Gilmore on their 1957 Blowing in Chicago effort.) As a soloist, the tenor man possessed that combination of concision and grit that proved to be essential for a Silver horn. The compatibility of Jordan and Farmer had more far-reaching consequences. While the pair only recorded together on one other occasion at the time (Jordan's November 1957 Cliff Craft), they would reunite once the now-flugelhorn-playing Farmer began returning to the US from his Vienna home in the late-'70s. That pairing, in bands under Farmer's leadership, would continue until Jordan's death in 1993.

Personnel probably had less to do with the historic status of Further Explorations than a critical absence in its program. For all the magnificent writing here, there is no soul tune on the order of "The Preacher," "Doodlin'," "Senor Blues," or "Home Cookin'," each a funky opus that spurred the sales of previous Silver LPs when simultaneously released as singles. It takes nothing away from the musical quality of "The Outlaw" and "Pyramid," the titles extracted for singles release from this album, to concede that they lacked the basic touch of Silver's previous hits. Silver made sure that his subsequent albums included the likes of "Juicy Lucy," "Sister Sadie," "Me and My Baby," and "Filthy McNasty."

Looked at in a more positive light, the program here is a clear indication that Silver was gaining confidence and curiosity as a composer. Exhibit A is "Melancholy Mood, " the best of Silver's early ballad writing and an audacious 28-bar form. (The piece would be revisited, in a new arrangement inspired by pianist Gil Coggins, less than two years later on Blowin' the Blues Away.) An even more challenging structure, the 54-bar "The Outlaw, " displays the skill of both composer and improvisers by retaining the chorus structure for both solo and shout choruses. "'Safari which was included on Silver's debut session for Blue Note in 1952, was the first indication that his early trio creations could be successfully enhanced in the quintet setting. Then there are such subtle touches as the horn voicings that add a desert vibe to "Pyramid, " the way the piano's syncopations add mystery on the same track, and the painterly detail of Hayes behind the ensemble chorus on "Moon Rays." Silver may not have known the correct name of the Latin effect he requested on this last title, but he clearly had no doubts about what the musical scene required.

So, exceptional playing plus exceptional writing equals another exceptional Horace Silver album. One that even many longtime fans will now have the pleasure of discovering.

— Bob Blumenthal, 2007

No comments:

Post a Comment