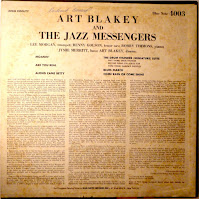

Art Blakey And The Jazz Messengers

Released - November 1958

Recording and Session Information

Van Gelder Studio, Hackensack, NJ, October 30, 1958

Lee Morgan, trumpet; Benny Golson, tenor sax; Bobby Timmons, piano; Jymie Merritt, bass; Art Blakey, drums.

tk.1 Are You Real

tk.4 Moanin'

tk.7/9/12/14 The Drum Thunder Suite

tk.16 Along Came Betty

tk.19 Blues March

tk.21 Come Rain Or Come Shine

Session Photos

Photos: Francis Wolff

Track Listing

| Side One | |||

| Title | Author | Recording Date | Duration |

| Moanin' | Bobby Timmons | 30/10/1958 | 09:35 |

| Are You Real | Benny Golson | 30/10/1958 | 04:50 |

| Along Came Betty | Benny Golson | 30/10/1958 | 06:12 |

| Side Two | |||

| The Drum Thunder (Miniature) Suite | Benny Golson | 30/10/1958 | 07:33 |

| Blues March | Benny Golson | 30/10/1958 | 06:17 |

| Come Rain Or Come Shine | Harold Arlen, Johnny Mercer | 30/10/1958 | 05:49 |

Liner Notes

Not for nothing did Art Blakey select the term Messengers to denote his musical and personal purpose at the onset of his bandleading career. Manifestly all meaningful music carries its own built-in message, and to this extent the term could reasonably be applied to any combination of performers. What is more important in Blakey's case is that his message is transmitted not merely in his music but in his words and speeches, his actions and personality.

Of the personnel heard on these sides, the horns of Lee Morgan and Benny Golson are too familiar to Blue Note fans to need any introduction, as is Bobby Timmons' piano. There is, however, one newcomer in the house, an artist talented and promising enough to deserve a momentary spotlight. He is bassist Jymie Merritt.

The session racks up a self-challenging achievement by starting right out with a climax, for it would be difficult to improve on the groove established by Bobby Timmons' composition "Moanin'." The first chorus is the quintessence of funk, based on the classic call-and-response pattern, with Bobby's simple phrases answered by the horns. Lee's solo opens, fanning out slowly in impact and intensity until by the first release he is swinging in a more complex fashion. Two choruses each by trumpet, tenor and piano are followed by one on bass.

"Are You Real?" is the kind of straightforward melody that could as easily have been a pop song designed by one of the better commercial tunesmiths. After Benny's busy but well-organized chorus, Lee takes a solo that reminds one again how impressively this youngster has been developing. Timmons, too, has a chorus that moves smoothly from phrase to phrase, with discreet help from the horns' backing on the release.

"Along Came Betty," a wistful theme played by the horns in unison, was inspired not by the personality but, curiously, by the walk of the young lady for whom it was named. If the music reflects her gait accurately Betty walks at a moderate pace with evenly placed, legato steps. Notice in Lee's chorus the wry simplicity of the first few measures in his last eight bars. Benny too, tends to underplay in his solo, while Art's subterranean swells at bars 8 and 16 are the only changes of pattern in an otherwise unbroken and unflaggingly efficient rhythmic support.

The second side opens dynamically with Golson's "Drum Thunder Suite," a work in three movements, which was born of a desire on Art's part to play a composition making exclusive and dramatic use of mallets. Since mallets automatically tend to suggest thunder, the title was selected, says Golson, before a note was written.

The implications of "Blues March" are clear from the first measure. An attempt is made here (with considerable success) to fuse some of the spirit of the old New Orleans marching bands with the completely modern approach of improvisation as it is felt by the present-day soloists featured here. It is rewarding to study the way in which Art supports the solos by trumpet, tenor and piano with a heavy four-four rhythm that escapes any suggestion of thudding monotony, yet retains the marching mood established by the introduction. Timmons' solo is quite striking in its gradual build from a simple one-note line into an exciting chordal chorus.

"Come Rain or Come Shine" is a reminder that Blakey has found the secret of reconciling the hard bop temperament of his band with the melodic character of a typical standard tune. The melody is slightly rephrased through the use of syncopation, the horns introduce it in unison and the soloists take over for a quartet of choruses--Timmons, Golson, Morgan, Merritt--that are no less a reflection of the Messengers' essential qualities than anything else in the set.

-LEONARD FEATHER

(Author of The Book of Jazz, Horizon Press)

Cover Photo by BUCK HOEFFLER

Recording by RUDY VAN GELDER

RVG CD Reissue Liner Notes

NEW LOOK AT MOANIN'

Staying with the youngsters," a credo Art Blakey espoused from the bandstand of Birdland five years earlier, was reaffirmed in no uncertain terms on this album. The drummer had celebrated his 39th birthday three weeks before entering Rudy Van Gelder's studio for the return of the Jazz Messengers to Blue Note, following the group's brief affiliations with Columbia, World Pacific, Savoy, Elektra, Bethlehem and RCA. This was a new group, with members separated in age by nearly two decades; yet Blakey rose to the challenge much as the equally venerable Miles Davis did a few years later when introducing his ESP band of younger players. In both cases new blood bred a new era, as well as leading in the present instance to one of the most beloved albums in jazz.

Excepting Pittsburgh native Blakey, this was an all-Philadelphia edition of the Messengers that found each sideman coming into his own. The precocious trumpeter Lee Morgan, no longer either a teenaged phenom or under the shadow of Dizzy Gillespie in the latter's trumpet section, had blossomed into an astounding stylist, and his power and expressive brilliance here sustain the maturation documented in the previous year on his own Blue Note sessions The Cooker and Candy. Bobby Timmons, himself only 22 yet a label familiar since his Cafe Bohemia session with Kenny Dorham, also emerged here from the ranks of fluent Bud Powell disciples to the ranks of a recognizable stylist whose affinity for the sanctified (as a soloist, and even more importantly as a composer) was critical in defining the era's soulful zeitgeist, Jymie Merritt's work was less familiar to jazz listeners of the time, yet (as Leonard Feather's original notes make clear) his decade-long apprenticeship in rhythm and blues, blues, mainstream jazz and modern jazz had formed an approach to the bass that was a model of intelligent melodic choices, steadfast time and selfless strength. Notwithstanding the contributions of Morgan, Timmons and Merritt, there is no disputing that Benny Golson defined this edition of the Messengers. Three months short of his 30th birthday and the veteran of affiliations that overlap those of his hometown friend and contemporary John Coltrane, Golson was extremely well prepared to serve as musical director of the group. Golson's playing and writing had been featured in the recently dissolved Gillespie orchestra that also included Morgan, as well as on several of Morgan's early Blue Note albums; but his contributions here are even more imposing. It was Golson who recruited his fellow Philadelphians for service with Blakey over the course of 1958; and while the sanctified Timmons composition "Moanin"' became the album's runaway hit, it was Golson who was responsible for the majority of the material. He met the challenge of spotlighting the leader with the substantial "Drum Thunder Suite" (which delivers a wealth of melodic material while also creating a context for Blakey's exceptional mallet work) as well as the infectious "Blues March," which did as much to establish Blakey's trademark shuffle groove as "Moanin'." The Messengers' "March" quickly eclipsed the original recorded version of the tune, which Blue Mitchell had cut with Philly Joe Jones drumming for Riverside tour months earlier. Golson's more lyrical side comes through on "Are You Real?" in the tradition of such earlier long-lined efforts as "Just By Myself," and the magnificent "Along Came Betty," as indelible a melody as any Golson has penned and perfectly orchestrated and executed to boot. These four compositions, as least two of which are classics, represent a level of output that was commonplace for Golson in the late fifties — and with "Moanin"' added create a bounty of original material that any bandleader would envy. Golson's contribution to the overall effort as both composer and instrumentalist matched the earlier impact of Horace Silver and anticipated the contributions of such future Messengers as Wayne Shorter, Bobby Watson and Donald Brown. Timmons, who like Morgan served more than one term with the Messengers, would later supplement his more modest yet equally pivotal contribution to the Blakey book with "Dat Dere" and "So Tired."

None of this in any way diminishes Blakey's personal triumph here. Much like the dignified cover portrait by Buck Hoeffler (rather than Blue Note mainstay Frank Wolff), the album presents a definitive image of the drummer-leader, one that gave new emphasis to the strutting dance-oriented figurations in Blakey's arsenal. Some commentators were upset with this stress on the backbeat ("a drastic simplification of the Messengers' usual polyphonic approach, " Max Harrison lamented), although both the results here and in further editions of the band demonstrate that Blakey was still ready to lead more straight-ahead charges and delve further into the music's African and Afro-Latin sources. What the backbeat really delivers here is the complete Art Blakey, which makes this collection (originally known simply as Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers) one of the essential chapters in the history of jazz rhythm, and, therefore, of jazz itself.

— Bob Blumenthal, 1999

Blue Note Spotlight - January 2014

http://www.bluenote.com/spotlight/art-blakey-the-jazz-messengers-moanin/

The first onstage school of jazz ultimately opened for long-term session with drummer Art Blakey who enlisted young players to his revolving-door group, the Jazz Messengers, not only to teach but also to continually refresh himself and his band with new energy, excitement and especially repertoire. (During a 1954 live session, At Night at Birdland, Blakey remarked during the set: “I’m gonna stay with the youngsters. When these get too old I’ll get some younger ones. Keeps the mind active.”) The Messengers was co-founded in the early ‘50s by Blakey and pianist/talented songwriter Horace Silver, who bowed out in 1956 to pursue his solo career.

Throughout its existence, the Messengers served as the proving ground for dozens of greats, from tenor saxophonist Hank Mobley to trumpeter Wynton Marsalis. A select sampling of impressive musicians who learned at the feet of the bass drum and elevated at the high hat of Blakey: pianists Wynton Kelly, Keith Jarrett, John Hicks, Cedar Walton, James Williams, Benny Green; saxophonists Jackie McLean, Lou Donaldson, Gary Bartz, Johnny Griffin, Branford Marsalis, Donald Harrison, Bobby Watson, Kenny Garrett; trumpeters Clifford Brown, Woody Shaw, Freddie Hubbard, Donald Byrd, Terence Blanchard; bassists Wilbur Ware, Reggie Workman, Doug Watkins; guitarists Bobby Broom, Kevin Eubanks. Quite a crew.

Blakey had an uncanny sense of bringing fresh-to-town artists who made their marks on the Messengers as rising stars, who then left for greener pastures—which was fine with the leader because that’s how the in-and-out personnel policy of the group worked. School 24/7, grinding tours, playing to top form with no slouching, then graduation and hopefully onward and upward.

One of the greats that Blakey mentored was tenor saxophonist Wayne Shorter, who in the late ‘50s to early ‘60s became the music director of the band and primary composer. He delivered several new songs to the Messengers set list, including “Chess Players,” “Lester Left Town,” “Children of the Night,” “Ping-Pong” “On the Ginza” and “Mr. Jin” among many others. After five years (a long term) with Blakey, Shorter jumped ship and joined Miles Davis’s soon-to-be-classic quintet.

Shorter’s work gave new life to Blakey’s band, but none of his tunes were as seminal and long-lasting as the batch of compositions that were released on the Messengers’ 1958 classic, Moanin’. The album stands as one of jazz’s all-time recordings, largely because of its tunes, including the hip and swinging “Moanin’” by 22-year-old pianist Bobby Timmons’ that opens the date and four songs by 29-year-old musical director and tenor saxophonist Benny Golson: the relaxed “Along Came Betty,” “Blues March” (complete with Blakey’s military drum beat opening the number), the lyrical “Are You Real?” and the powerful “The Drum Thunder Suite.” A hard-bop cover of the Harold Arlen and Johnny Mercer tune “Come Rain or Come Shine” closes the six-pack. Quintet personnel on the date also includes very young trumpeter Lee Morgan (soon to be a huge Blue Note star in his own right) and bassist Jymie Merritt.

“Moanin,’” “Along Came Betty,” “Blues March” and “Are You Real?” are all played to perfection by the band and not only deservedly became integral to Blakey’s songbook, but have also found their place in the jazz canon. However, often overlooked is the compelling three-movement drum piece Golson wrote for Blakey who stars with gusto. “The Drum Thunder Suite” opens with mallet thunder with the horns driving the storm, continues with the Latin-tinged middle section and the closing funky melody that features Morgan on a clarion trumpet solo.

It’s rare that a jazz album—let alone a pop album—includes so many “hits.” That’s what Blakey accomplishes on Moanin’ with ease, swing and rumble.

Udiscover Music Review

https://www.udiscovermusic.com/stories/hard-bops-signature-tune/

It was at Rudy Van Gelder’s Studio, Hackensack, New Jersey, on October 30, 1958, that Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers’s classic album Moanin’ was made.

“This is take four,” says Rudy Van Gelder just before the band breaks into pianist Bobby Timmons’s composition and one of the most recognizable themes in jazz. As an opening track “Moanin” is just about as perfect as it gets and has been called one of hard-bop’s signature tunes. The track was so popular it led to Blakey and the Messengers’ eponymous album being referred to as “Moanin’” by almost everybody, and the title stuck. The track was also released as a single, its nine minutes split over both sides of the 45 in February 1959. Billboard had this to say about it: “Fine offering from Blakey and the Messengers. It’s a smart tune that features fine solos over Blakey’s percussive urging. Pop jockeys may also find these spinnable sides.”

“Moanin’” may never have happened if it hadn’t been for Benny Golson’s insistence that 22-year-old Timmons complete the little eight-bar motif that he would often play between tunes at the band’s gigs. Credited with putting the funk back into jazz and an irresistible number, just this one track would have made the album memorable, but it is outstanding from start to finish. Golson takes over the writing of the remaining tracks, bar the album’s closer, which is the Johnny Mercer and Harold Arlen standard.

Having begun his recording with the Blakey band just two years earlier, Lee Morgan was still only 20 years old when they made this record – hard to believe when you hear the sophistication of his playing and his empathy with Golson who was almost a decade older.“I come in very loud,” Morgan warned Van Gelder just prior to recording take 4 of “Moanin,” and indeed he does, but nothing can detract from the soulfulness of his trumpet playing. A star was born.

Side two of Moanin’ opens with Blakey’s suite, a “schizophrenic symphonic showpiece” that has everything from bebop to bossa nova. And by the time the album finishes with “Come Rain or Come Shine” – Timmons proving he’s no slouch on the keys – you are completely sold on the Jazz Messengers’ sound. Back in 1959 so was just about everyone else: this was the album that established them as one of jazz’s premier outfits.

No comments:

Post a Comment