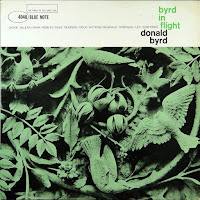

Donald Byrd - Byrd in Flight

Released - January 1961

Recording and Session Information

Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, January 17, 1960

Donald Byrd, trumpet; Hank Mobley, tenor sax; Duke Pearson, piano; Doug Watkins, bass; Lex Humphries, drums.

tk.8 Gate City

Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, January 25, 1960

Donald Byrd, trumpet; Hank Mobley, tenor sax; Duke Pearson, piano; Doug Watkins, bass; Lex Humphries, drums.

tk.17 Ghana

tk.18 Lex

Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, July 10, 1960

Donald Byrd, trumpet; Jackie McLean, alto sax #2,3; Duke Pearson, piano; Reginald Workman, bass; Lex Humphries, drums.

tk.6 Little Boy Blue

tk.14 Bo

tk.16 My Girl Shirl

Session Photos

|

| Donald Byrd |

Track Listing

| Side One | ||

| Title | Author | Recording Date |

| Ghana | Donald Byrd | 25/01/1960 |

| Little Girl Blue (mistitled Little Boy Blue) | Richard Rodgers, Lorenz Hart | 10/07/1960 |

| Gate City | Duke Pearson | 17/01/1960 |

| Side Two | ||

| Lex | Donald Byrd | 25/01/1960 |

| Bo | Duke Pearson | 10/07/1960 |

| My Girl Shirl | Duke Pearson | 10/07/1960 |

Liner Notes

I'VE BEEN particularly intrigued with the development of Donald Byrd since I first heard him in the fall of 1955. He was just beginning his New York apprenticeship then, and although his playing was occasionally tentative, I remember especially the refreshing airiness with which he played at his best. He had a quicksilver attack; one listener at the time likened him to a hummingbird. And although he could play with bold fire, Byrd also was one of the most lyrical of the newer hornmen in an era when lyricism was a rare and suspect quality in modern jazz.

In the past five years, as Byrd has gained experience and assurance, his tone has become stronger and his conception has distinctly matured. Byrd, however, has not lost the light-heartedness and buoyancy that first set him off from many of his contemporaries. He has not allowed himself to be limited to the wholly aggressive language of the ”hard boppers” or the repetitious exclamations of the lesser ”soul” searchers.

In this album, Byrd has evolved even further toward a style that is his own and that is becoming broader in the range of emotions he can project. The opening Ghana, for example, connotes the jubilation of a new nation as well as its determination to remain its own master. Byrd’s solo is constructed with a flowing logic and that feeling of airiness I referred to before. Complementing him is pianist Duke Pearson, originally from Atlanta. Since coming North, Pearson has worked with a group led by Byrd as well as with other combos. Pearson too is a supple, lyrical musician who plays with a light touch, a thoroughly pianistic tone, and a satisfying sense of order. Hank Mobley, now a veteran modernist, adds by contrast a bigger sound and more driving attack but he too sustains the optimistic spirit of the work. Lex Humphries contributes a celebratory solo and the band returns to Byrd’s infectiously ebullient theme.

Little Boy Blue underlines Byrd’s increasing mastery of the jazz ballad. He has an open tone that is attractively brassy without being strident, and he shades it with impressive control. In this interpretation, Byrd shows how close a thorough jazzman can stay to the melody and yet - by phrasing, timbre and rhythmic pulsation - produce a fully personal jazz performance. A good many young trumpeters who ”run changes” with the headlong speed of antelopes would have considerable trouble sustaining the kind of thoughtful line and the unpinched, expansive tone that Byrd achieves. Similarly, several of the more ”funky” pianists couldn’t match the graceful, romantic (but not saccharine) solo Pearson lines out here.

Pearson and Byrd also feel the blues strongly, as Pearson’s Gate City indicates. Donald's opening solo is effectively uncluttered. He has learned the usefulness of economy and the challenge of finding the right notes rather than running all over the horn and thereby diffusing his message. Mobley’s solo is also sparely shouting (note, incidentally, Pearson’s resilient, tasteful comping). Pearson himself is convincingly ”down” in his statement without sacrificing the singing quality that is at the base of his style. (For Pearson at full length, I’d suggest his initial Blue Note album, Profile: Duke Pearson, Blue Note 4022, which contains a trio version of Gate City Blues.)

Lex is another festive Byrd original on which Donald takes a characteristically fleet solo that sometimes seems to wheel and dart much like a bird in contrast to the considerably more earthbound sound and phrasing that have become familiar in modern jazz. There is an agility and a kind of guilelessness in Byrd’s work that this listener finds appealing. Mobley again sets off Byrd’s careening with his own robust, straight-ahead drive. Pearson has what is for me one of his most thoroughly delightful solos in the album, a sunny structure with a judicious choice of notes and a limber, dance-like sense of swing.

Pearson is also a composer of unpretentious naturalness and economy of line, as the rollingly relaxed "Bo" demonstrates. Present here is Jackie McLean, who has developed strikingly in the past couple of years. He too has learned the musical advantages of functional, non-decorative playing; and his emotional message, which was always strong, has begun to take on added shades besides harsh insistence. Byrd’s solo is practically a ”talking” one, so natural and speech-like are its cadences. Note again Pearson’s poise and clarity. His is unfeverish, reflective jazz piano that communicates grace as well as ”roots."

Pearson is also responsible for My Girl Shirl, an intriguingly sinuous line. McLean bursts into a solo that is marked by his characteristic concentrated emotion, slicing beat, and emotional thrust. The album, incidentally, wisely joins the swiftly flying Byrd and the translucent Pearson with two hornmen, Mobley and McLean, who are more fierce in their expression. The result is more contrast in color and mood than is usual in albums of this genre.

In essence, what sets this album off from many modern jazz sets of the year is its high quotient of merriment, a word not often used to describe much current playing. Byrd has come through a decade in which a considerable percentage of modern jazz reflected unyielding aggression; and yet he has consistently concentrated on the more cheerful aspects of the music. He certainly can play the blues and can be intensely introspective in ballads, but he is also able to romp through medium-tempo and up tempo swingers with a carefree zest and sheer delight in making music that place him in a distinctive category. Duke Pearson is another young jazzman who clearly gets joy out of the shifting challenges of improvisation, and is closely allied in the relative serenity of his musical temperament to Byrd.

Much of the reason that jazz continues to hold the interest of listeners who have been collecting since their early ’teens is that it can reflect so many variegated emotions and personalities. And Donald Byrd's is one of the more relaxed personalities of the contemporary scene. There is a Puckish, fun-and-games aura to his music as well as clear, strong feeling for melody that make his performances a welcome oasis of spring-like enthusiasm. This is such an album - music for its own sake with youthful freshness and the kind of swing that lifts the listener rather than hammers him into submission.

- NAT HENTOFF, Co-Editor, The Jazz Review

Cover Photo and Design by REID MILES

Photo by FRANCIS WOLFF

Recording by RUDY VAN GELDER

No comments:

Post a Comment