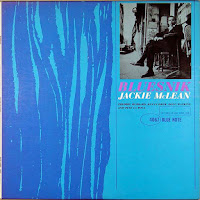

Jackie McLean - Bluesnik

Released - January 1962

Recording and Session Information

Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, January 8, 1961

Freddie Hubbard, trumpet; Jackie McLean, alto sax; Kenny Drew, piano; Doug Watkins, bass; Pete La Roca, drums.

tk.5 Blues Function

tk.7 Cool Green

tk.8 Goin' Way Blues

tk.15 Torchin'

tk.20 Drew's Blues

tk.20A Bluesnik

Session Photos

Photos: Francis Wolff

Track Listing

| Side One | ||

| Title | Author | Recording Date |

| Bluesnik | Jackie McLean | 08 January 1961 |

| Goin' 'Way Blues | Jackie McLean | 08 January 1961 |

| Drew's Blues | Kenny Drew | 08 January 1961 |

| Side Two | ||

| Cool Green | Kenny Drew | 08 January 1961 |

| Blues Function | Freddie Hubbard | 08 January 1961 |

| Torchin' | Kenny Drew | 08 January 1961 |

Liner Notes

THE blues are here to stay. They pre-dated jazz, helped form it and have been present through all its periods. Jazz without the blues would be a body minus is spine.

In retrospect, it is ironic to remember that Charlie Parker was derided by his many critics for having no feeling and accused of leaving jazz to play another music, when all the time he was basically a powerful blues player. Later it become obvious to almost everyone that although his was a new means of expression, the roots of the blues were there to see, touch and hear.

The charges leveled at Parker were naturally also hurled at the musicians who developed from him. But all the men who came out of his “school” have been players who do not hide their emotions. They all can blow the blues.

Jackie McLean is a perfect example. He has really come into his own in the past two years but long before that he was able to move the listener by direct emotional contact. The blues have always been a basic part of his musical language. Like any player worth your attention, he brings this essence of jazz to material other than the blues without making everything into a blues as some of today’s “soulniks” seem to do.

This, however, is a blues date and Jackie gives all six selections the full treatment. There is no mistake about what is going down here; the music is rich, full of all shades of blue feeling and driven by a pulse that not only is a model of forward motion but which has depth, breadth and width too.

McLean’s playing was once described as hurt, lonely and, as a result, angry. This was true of an earlier Jackie. Today he is still very much a hard swinger but the anger has abated to a large degree. He has matured in many ways and this is reflected in his music. The albums for Blue Note in the last two years bear this out. I would dispute Nat Hentoff's calling Jackie “unsentimental” in his review of Capuchin Swing (Blue Note 4038) in the April 1961 Hi Fi/Stereo Review, although he did not mean it as a put-down. McLean does not espouse sentimentality, to be sure, but neither does he avoid honest sentiment and tender moments as the word “unsentimental” might imply. Any player with Jackie’s fire gives off intense heat but in addition to the molten there is a warmth that does not burn.

A player-actor in Jack Gelbert’s The Connection since its July 1959 opening, McLean went overseas in early 1961 with the original cost for its London engagement, also playing concerts with drummer Arthur Taylor In several European countries.

Freddie Hubbard, who shares front-line duties here, has been garnering much praise lately, most of it due to a successful string of Blue Note recordings, both as leader and sideman. The assurance of execution and, even more so, conception that Hubbard continually displays, belies the fact that he is still in his early twenties. Though he has the brilliant, brassy bite of a real trumpet player, he is no rhetorician. Freddie has something to say and does it without wasting words. Hear Open Sesame (Blue Note 4040) and Goin’ Up (Blue Note 4056).

In writing about Jackie McLean, I have often referred to the “neighborhood band” of his youth which included Sonny Rollins and Art Taylor. The two pianists who split the weekend assignments then, were Walter Bishop and Kenny Drew. Now in the Fifties, they have token up where they left off in the Forties. Bishop was the pianist on Swing Swang Swingin’ (4024) and Capuchin Swing (4038). Drew played also on Jackie’s Bag (4051).

While the regular Connection cast was away, Kenny served as Freddie Redd’s replacement. He also has made appearances in the recording studio for Blue Note. Undercurrent (4059) is a Drew-led session with all compositions by Kenny. Long ago, he proved to everyone that he knows how to play the blues. In Bluesnik, he reiterates that strongly.

Doug Watkins, another of the many talented Detroiters to migrate east in the Fifties, has not been heralded as loudly as some of his compatriots but is a valuable rhythm player nevertheless. Several writers, however, have concurred on his great ability in the blues idiom, wherein he seems to speak in an especially effective manner. As one of Art Blakey’s original Messengers (vintage 1955), Doug is no stronger to Blue Note listeners.

Like many important musicians before him, Pete La Roca mode his recording debut for Blue Note on part of a Sonny Rollins album. His solo on Minor Apprehension is one of the highlights of Jackie McLean’s New Soil (Blue Note 4013). Influenced by Philly Joe Jones and Elvin Jones, La Roca is one of the most dynamic young drummers in jazz. The beat he lays down in this album is extremely muscular and controlled.

Listen (courtesy of Rudy Van Gelder) to Pete’s exciting cymbal in conjunction with Watkins and Drew as they drive relentlessly behind McLean on his free-flying Bluesnik which opens the set. This is a highly-charged number with Jackie rhythmically and vocally adventuresome, Hubbard hot and urgent and Drew articulate. A fantastic swing and spirit is continuously in motion.

Goin’ ‘Way Blues is also by Jackie. It is in a definite down-home groove with La Roca setting up a rhythmic contrast to the horns as they state the theme and then settling into a solid four to back the passionate McLean. Hubbard follows with one of his typical declarative statements and Drew has a brief, but down and dirty, solo. Kenny returns after the theme with a final punctuation.

Drew’s Blues is by Kenny. It is at an easy, loping tempo and stylistically reminiscent of Soft Winds in some ways. The feeling is anything but soft as everyone digs in to make his point. Each soloist receives impetus from short springboard “breaks” just prior to his featured spot.

Another Drew original is Cool Green, a minor blues that, in addition to direct, open, moving solos from the principals, contains the only Watkins solo of the set.

Blues Function by Freddie Hubbard is, like its title implies, a functional blues. It might be added that everyone performs his function in a functional manner. Freddie has the first offering. It is typically economical and delivered with his personal sound. Jackie is particularly pleading in his blues cause while Drew indicates that he, like many instrumentalists, has been listening to John Coltrane.

Kenny’s Torchin’, in a relaxed vein, makes use of suspended rhythm in its 16-bar pattern. It is a brother to Sonny Rollins’ Doxy and other tunes which spring from the How Come You Do Me Like You Do chord sequence. Its undiluted blues mood is explored by all three soloists before the return of the theme. Drew adds a pianistic “amen” and Watkins’ bow seconds him.

The blues, in general, are on the rise. The older singers like Lightnin’ Hopkins and John Lee Hooker are recording extensively; Roy Charles, although he is doing a lot of “pop” material, is still primarily a blues performer and his main appeal lies in that direction; and the young moderns are very involved with their own interpretation of the blues, taking some older elements and fusing them with the new. The groups of Horace Silver and Art Blakey are vivid exponents of this concept. Jackie McLean’s Bluesnik is yet another powerful manifestation of the contemporary blue attitude.

—IRA GITLER

Cover Photo by FRANNIS WOLFF

Cover Design by REID MILES

Recording by RUDY VAN GILDER

RVG CD Reissue Liner Notes

A NEW LOOK AT BLUESNIK

There are several candidates for best Jackie McLean album in the Blue Note catalog, and Bluesnik got the nod from five respected British critics when they chose an example of his work for the 1975 survey Modern Jazz 1945—70: The Essential Recordings. Michael James, one of the alto saxophonist's earliest champions, noted that McLean's Blue Note dates of 1959—61 were "on balance, more consistently rewarding than those he set down before or afterwards," and that Bluesnik was "the most forceful of them all," citing McLean's "absorption in fresh means of melodic expression based on a freer use of rhythm and harmony his tonal power and the emotional edge to his music and [how] the blues could hold the listener spellbound...when interpreted by a player of mature experience within that traditional but demanding form."

While the relative merits of Bluesnik vis-å-vis later McLean albums can be debated, James undoubtedly hit upon the album's strengths, which are nowhere more obvious than in the scorching title track. The six-note thematic figure is basic in the extreme, yet McLean stretches it into several provocative shapes while sustaining an overall coherence of stunning impact. As a blues manifesto, "Bluesnik" is a critical step in his evolutionary path that links the previous year's "Francisco" (from Capuchin Swing) and 1962's "Rene" (from Let Freedom Ring). The other titles here are not far behind in quality, and form a program with surprising variety.

If the album is typical in its documentation of McLean in evolution, it also can be seen as something of an endpoint in terms of supporting personnel. The rhythm section in particular is filled with familiar faces whose work with the saxophonist either stops here or enters a prolonged hiatus. Doug Watkins, present on McLean's 1955 Ad-Lib debut as a leader and many of his subsequent sessions, was killed in an automobile accident early in 1962. Boyhood friend Kenny Drew, who recorded with the saxophonist only once before but also contributed the composition "Contour" to a McLean album on Prestige, left the US and established residence in Europe a few months after this recording. A dozen years would pass before the pair joined forces again with the tapes rolling.

More surprisingly, this is the last collaboration-between McLean and drummer Pete La Roca. The "'Minor Apprehension" solo that original annotator Ira Gitler mentions had drawn wide praise for its visionary approach to jazz percussion, and La Roca continued his exploratory ways before leaving music for a legal career in 1968. His work with first Scott La Faro and then Steve Swallow behind several of the period's most inquisitive pianists (Paul Bley, Don Friedman, Steve Kuhn), not to mention his extensive earlier association with Sonny Rollins in a trio format, mark him as an ideal partner for McLean's subsequent evolution; but it was not to happen. Freddie Hubbard, the only new face here as far as McLean albums was concerned, also would have felt at home with the direction the saxophonist's music was about to take; but McLean chose to employ Grachan Moncur's trombone rather than a trumpet when he formed his classic 1963 quintet, then partnered with newcomers Charles Tolliver and Woody Shaw as well as old friend Lee Morgan when he brought the horn back into his ensembles. Hubbard and McLean would meet only one additional time on record, as part of a 1989 Art Blakey tribute taped in Leverkusen, Germany.

The two alternate takes first appeared on the album's initial CD reissue in 1989, and come from the middle of the recording session. "Goin' Away Blues" was done first with the master take preceding the alternate, and was followed by the alternate of "Torchin'" and then the master. In both cases, the masters feature stronger solos, particularly in the case of Hubbard on "Goin' Away."

As for the writing, " Blues Function" is functional indeed, a basic pattern in the lineage of Sonny ClarkS "Cool Struttin"' and Lou Donaldson's "Blues Walk." Drew's three compositions are more memorable, especially "Cool Green" with its evocative introduction, yet none exists in other versions. (This "Drew's Blues" is not the composition of the same title heard on the pianist's 1953 Blue Note trio date.) McLean did revisit "Bluesnik" in 1996 on Hat Trick, his Blue Note meeting with pianist Junko Onishi. He also employed the line when he teamed with Gary Bartz on the 1973 SteepleChase album Ode to Super, but in that instance it was given a funk beat and the alternate title "Great Rainstreet Blues."

— Bob Blumenthal, 2008

No comments:

Post a Comment