Jimmy Smith - Midnight Special

Released - October 1961

Recording and Session Information

Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, April 25, 1960

Stanley Turrentine, tenor sax; Jimmy Smith, organ; Kenny Burrell, guitar #3-5; Donald Bailey, drums.

tk.2 A Subtle One

tk.5 Why Was I Born

tk.12 Midnight Special

tk.17 One O'Clock Jump

tk.19 Jumpin' The Blues

Track Listing

| Side One | ||

| Title | Author | Recording Date |

| Midnight Special | Jimmy Smith | 25 April 1960 |

| A Subtle One | Stanley Turrentine | 25 April 1960 |

| Side Two | ||

| Jumpin' the Blues | Walter Brown, Jay McShann, Charlie Parker | 25 April 1960 |

| Why Was I Born? | Oscar Hammerstein II, Jerome Kern | 25 April 1960 |

| One O'Clock Jump | Count Basie | 25 April 1960 |

Liner Notes

DURING the summer of 1961 when Newton Minow, the Kennedy appointee as chairman of the Federal Communications Commission, leveled his blast at the television industry calling it "a vast wasteland," James Oscar Smith was quietly setting his sights to level his own private blast on video. When the count-down came, Jimmy loaded his organ guns and directed them at the television audience in the Philadelphia area. I was there watching him score a direct hit on his target.

His musical explosion shattered myths and produced amazing, eye-opening results that led the television audience stunned but begging for more.

Jimmy Smith's Philadelphia television debut came about through a number of interested people eager to produce good music locally. Main man was Jack Downey, alert Program Director of WCAU-TV (CBS in Philadelphia, where I am an Assistant Director in video); Jack gave his approval to include a jazz show on his "Experimental '61" series designed for employees of this CBS outlet to produce new program ideas for airing. The show I produced, "A Taste of Jazz," received the green light, and my first choice of musicians for the appearance was Jimmy Smith. With Jimmy was Donald Bailey and Quentin Warren, Who shared this OPUS with ex-Basie AllStars, the Al Grey-Billy Mitchell Sextet.

The half hour of music was a pure groove. Jimmy Smith displayed to a huge TV audience the reasons why he is called incredible. But most important were the reactions of the average TV viewers who had never heard of Jimmy Smith. They could not believe their eyes, much less their ears.

The jazz fans who know that Jimmy is the Number One jazz organist in the world and who are aware of the tremendous influence he has wielded in the jazz field had been busy keeping his goodies to themselves. People wanted to know who he was and how he learned to play an organ with such skill and flair.

The second on-target shot leveled some weeks later was a display of some of the most fantastic manipulations of organ keys and pedals ever seen. The brilliant display of the Jimmy Smith technique at work was seen and heard throughout the Philadelphia area. This time we took Jimmy to the NBC outlet in Philadelphia, WRCV-TV, for his appearance on the show we co-produced with Al Berkhoff, "The Del Shields Summer Showcase."

When the time arrived for Jimmy to come on, I was reminded of the story Jimmy tells about his first appearance in New York. I saw it when the musician and critics came out to view this cat who was "taking care of business" on the organ. All were wide-eyed and unbelieving. Some of them made it to the bandstand and everybody tried to get in on this rare moment when music and soul flowed freely. Jimmy had struck a groove. The stage hands were stunned and the Stage Director didn't know how to tell Jimmy to bring his solo to a halt. Finally I got up from my chair and stationed myself as close to the camera as possible, waving frantically for him to stop. At last he got my signal; but, meanwhile, history had been made.

To consistently meet challenges head on is not new for Jimmy Smith. This has been his forte since he first burst onto the jazz scene. Previous Blue Note albums had carried the fitting adjectives describing his superb technique. But what is needed is an in-depth study of Jimmy Smith, a fantastic human being who becomes The Incredible Jimmy Smith when he sits at his organ.

Throughout the jazz world Jimmy has earned from fellow musicians an astounding respect. His ability to act as catalyst and inspiration is even more unbelievable. Together we have entered clubs to watch other musicians play. When they became aware of him, could feel — and hear — a difference in their playing. If this is true, how much more so is it when the musician shares the bandstand with him — all of which brings us to this album and what happens on the latest of the Jimmy Smith testimonies. On Midnight Special, Stanley Turrentine produces a compelling sound at the insistent urging, pushing, and guidance of a Jimmy Smith at his inspiring best. This sound of Stanley's earmarks him for greatness. The infectious beat of Jimmy is heard throughout the album, making this musical marriage of Turrentine and Smith a rare one indeed. At a time when most of the tenor saxophonists (with an excepting respect for Coltrane & Rollins) are doing their darnedest to make the tenor horn sound like anything but, Stanley returns us to the sound of the elder statesmen of the big horn, tenor horn diplomats like Coleman Hawkins and Ben Webster. Yet Stanley has skillfully embodied some of the more modem approaches in his playing without losing the central appeal of the tenor and its beautiful tone!

We in the jazz world are constantly seeking a definition of jazz. Jazz is simply music. And music is what Jimmy Smith and Stanley Turrentine offer to you in this album. Good music may easily defy explanation, because it is mostly felt. This is a good music album.

It is also Jimmy's 18th album for Blue Note; and in it, Jimmy does not try to overpower you. Rather, it focuses on his ability to work and inspire another musician to reach unparalleled heights of expression.

Stanley Turrentine was introduced previously on Blue Note albums 4039, 4057, and 4069, and in his quest for acceptance and even greater expressive breadth, I feel he has reached a new and higher plateau via this Midnight Special.

"Midnight Special" opens the album and establishes, first, that this is going to be one of those good ones. Jimmy opens at a relaxed tempo and, as is his custom, starts to build. Stanley makes his introduction, giving credence to our earlier thought that the tenor must have depth of sound. Jimmy returns and you hear the great compatibility between him and Donald Bailey. After an extended solo, Jimmy skillfully moves aside as the guitar of Kenny Burrell takes over. This expatriate From the Motor City proves with his solo work that his engagements this summer (1961) in such Broadway outings as Bye, Bye Birdie and How to Succeed in Business without Really Trying were mere breadwinners and not soul-stealers.

"A Subtle One" is Stanley's original in this album and gives further proof that Stanley is a writer of meritorious note. Stan opens with a full sound, again making his horn a deep eloquent spokesman. Jimmy follows and proves that the "subtle" sound also belongs to the organ, his organ. Donald Bailey, as perennial head of the Jimmy Smith percussion section, tastefully blends his cymbals and snare to work — again, compatibly, with Jimmy. In all this, Kenny Burrell steadies the pace before the entire ensemble takes it out.

Side Two opens with the ensemble establishing the theme. "Jumpin' the Blues," From the Charlie Parker-Jay McShann book, has that good, Kansas City feeling. Stanley moves to take the first solo as Jimmy quietly nudges him, gradually coming in stronger himself to blend with Donald. Jimmy starts to build and then gives way to Kenny. Listen to Jimmy behind Kenny, never obtrusive, but always present, always swinging; when Stan returns briefly, the group takes it out in that sure way of groupness.

"Why Was I Born?" is one of the most beautiful tenor sax solos I have ever heard. The Kern-Hammerstein tune gives Stanley a showcase to produce a haunting, heart-throbbing sound that etches the lyrics For you. This is music. You sit back, hum, feel, and really wonder ... "Why?" Clear control, sharp tone ... this is the sound of Stanley Turrentine. And with all this, Jimmy is still astounding with his ability to create an almost feather-like sound as he accompanies Stanley.

In "One O'Clock Jump," Jimmy opens with bits reminiscent of Basie's approach. Stanley walks in and immediately you think of the late Lester Young — to Stanley's credit and to Lester's, you are reminded, too, that Stanley has listened to the late Prez, but not enough to lose his own tenor identity. Kenny takes over and then gives way to Jimmy. Listen to this rhythm section telling you what rhythm is supposed to have been all this time. Jimmy carries it out by bringing you a touch of Waller along the line; he walks away softly before the group returns for the final chorus.

— DEL SHIELDS

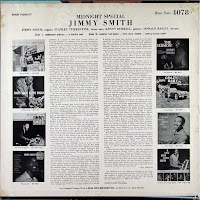

Cover Photo by FRANCIS WOLFF

Recording by RUDY VAN GELDER

RVG CD Reissue Liner Notes

A NEW LOOK AT MIDNIGHT SPECIAL

Jimmy Smith was no stranger to marathon sessions and prodigious output when he arrived at Rudy Van Gelder's studios on April 25, 1960, as several of the 17 previous album projects that Del Shields alludes to in his original notes to Midnight Special confirm. It was hardly unprecedented for Smith and his three colleagues to produce not one but two albums by the time their visit to Englewood Cliffs was complete. Even the release of Midnight Special and Back at the Chicken Shack as unaccredited but obvious companion discs could be traced back to Smith's linked jam sessions, House Party and The Sermon. What made this music unusual was the instrumentation, both planned and (one suspects) unplanned.

While the prototypical small group with organ is generally considered to contain tenor sax, guitar, and drums, this was not Smith's chosen setting. His working band was a trio sans sax; and while he had included tenor players on jam session projects where other horns also participated, his only previous quartet recordings with tenor had been a few tracks featuring Percy France on his Blue Note LP Home Cookin'. In Stanley Turrentine, Smith had the ideal tenor, and the saxophonist's contributions did much to both establish these discs as classics, and further his own nascent career. Turrentine was still in the midst of a nearly two-year tenure with Max Roach at the time, and had made his only previous appearance on a Blue Note session just three weeks earlier under the leadership of Dizzy Reece. The results of that day at Van Gelder's did not surface until 1999, on the Reece album Comin' On, but Alfred Lion was suitably impressed with Turrentine's work there to include him on the present date, which then led to a Blue Note contract and the appearance of three discs under the saxophonist's name before any of the present tracks with Smith were released.

Turrentine was clearly the right musician for Smith's first serious move into organ/tenor quartet territory — except that 40% of the music produced on April 25 is actually by an organ/tenor/drums trio. For reasons neither explained nor acknowledged in the original notes, Kenny Burrell joined the proceedings only after four tracks had been recorded. The always-busy Burrell may simply have been overbooked. Whatever the reason, his partial absence led to a mix of trio and quartet music on each disc.

"A Subtle One" was the first piece attempted and, despite Shields's claim that Burrell is present, one of two trio tracks on Midnight Special. A few organ groups have picked up on this excellent medium-tempo Turrentine line in recent years, though neither the composer nor Smith ever revisited it. The slow-burn nature of the performance finds Turrentine hitting some peaks in his second solo without going over the top.

"Why Was I Born?" is another trio number, with Smith applying some of the mellower stops on his organ console. As Shields emphasizes, Turrentine knew how to impose a world of feeling without disguising melodic content, and when the rhythm section goes into double-time, he also displays how to marry grace with weight. The saxophonist is featured throughout, which is both a rarity on a Smith session and a sign of the organist's estimation of the then virtually unknown tenor man.

The album's remaining three tracks include Burrell, who had been a frequent guest on Smith sessions since 1957. The burn on "Midnight Special" is even slower than on "'A Subtle One," and the ability of Smith and company to sustain the groove created a blues classic. Everyone is intensely self-contained, though Smith throws a curve when he changes keys shortly before the five-minute mark. The fadeout at the end is in keeping with the locomotif.

The remaining two titles are also blues, of the classic Kansas City variety, with Burrell doing his best Freddie Green comping on "One O'Clock Jump." There may be a bit of Lester Young in Turrentine's entrance, as Shields suggests, but the overall saxophone sound and attack are closer to Pres's tenor partner Herschel Evans. Smith's comping reminds us in spots of the organ's ability to suggest a big band in full flight, and his solo includes both sonic and spatial nods to Basie.

"'Jumpin' the Blues" is actually titled "The Jumpin' Blues," a bit of confusion that has lingered with this writer, who heard Smith's version before the Jay McShann original with the famous early Charlie Parker solo. This was the last track recorded at the session, and all members were still blowing strong.

(The companion album, Back at the Chicken Shack, is also available in an RVG edition.)

— Bob Blumenthal, 2007

No comments:

Post a Comment