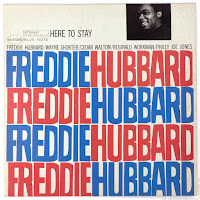

Freddie Hubbard - Here To Stay

Released - 1986

Recording and Session Information

Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, December 27, 1962

Freddie Hubbard, trumpet; Wayne Shorter, tenor sax; Cedar Walton, piano; Reggie Workman, bass; Philly Joe Jones, drums.

tk.4 Full Moon And Empty Arms

tk.9 Assunta

tk.18 Father And Son

tk.20 Nostrand And Fulton

tk.23 Body And Soul

tk.25 Philly Mignon

Session Photos

Photos: © Francis Wolff/Mosaic Images

https://www.mosaicrecordsimages.com/

Track Listing

| Side One | ||

| Title | Author | Recording Date |

| Philly Mignon | Freddie Hubbard | 27 December 1962 |

| Father and Son | Cal Massey | 27 December 1962 |

| Body and Soul | Green-Newman-Sour-Eyton | 27 December 1962 |

| Side Two | ||

| Nostrand and Fulton | Freddie Hubbard | 27 December 1962 |

| Full Moon and Empty Arms | B. Kaye, T. Mossman | 27 December 1962 |

| Assunta | Cal Massey | 27 December 1962 |

Liner Notes

Freddie Hubbard once claimed that when he first arrived in New York from his native Indianapolis in 1958, he was so intimidated by the local jazz scene that he didn't venture out of the house where he was staying for a month. If that's true, it must surely have been the only time in Hubbard's career that he manifested anything like reticence, and, he obviously got over it in a hurry!

The key word for Hubbard's approach to the trumpet on this 1962 session — and at any other point in his career — is confidence. He has been known to refer to himself on stage as "the world's greatest trumpet player," and to say of the music his group plays, "We don't call it jazz, we call it 'Freddie Hubbard music'", which may be taking things a bit too far. But there can be no doubt that his pride in his ability is both legitimate and justified.

Hubbard was only four years out of Indianapolis and only 24 years old when he recorded this album — which went unreleased for 14 years — but his confidence is quite apparent, as is the talent that was to make him, before long, one of the most influential improvising musicians of his generation.

At the time of this session, Hubbard was becoming known and respected for his work with Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers, where his predecessors included such masters of the trumpet as Clifford Brown and Lee Morgan (and his successors would include, among many others, Wynton Marsalis). As the outstanding institution of what used to be called 'hard bop,' the Jazz Messengers have always offered a pretty thorough schooling in how to play with energy, dexterity, harmonic acuity, and gutsy lyricism. Goaded on by the persistent thunder of Blakey's drums, Hubbard thrived in the Messengers and obviously felt at home. (Note that Here to Stay features three fellow Messengers — Wayne Shorter, Cedar Walton, and Reggie Workman — in the supporting cast.)

The early-sixties was a period of remarkable excitement and activity at the Blue Note label. The fiery, explorative jazz that was a hallmark of Blue Note in those years never reached that wide an audience, but the quality and consistency of the music, and of the young, adventurous players who were making it, was remarkable. Hubbard, who recorded prolifically for Blue Note as both leader and sideman (with Blakey, Bobby Hutcherson, Herbie Hancock, and others), was an integral part of what the label was all about.

Hubbard was, in a way, the ideal Blue Note musician. He fit right into the hot and heavy musical milieu that mixed elements of bop, down-home funk, the "free jazz" that Ornette Coleman and others were pioneering, and the modal approach of John Coltrane and his disciples, to produce a body of music that served as a welcome relief from the increasingly effete and restrained sounds of what came to be known as "cool" jazz. He attacked the trumpet in a way that emphasized the brassy nature of the instrument — its attention-getting volume, its upper-register power, the golden clarity of its sound. Trumpeters since Louis Armstrong (if not earlier) had been approaching the instrument this way, but at the time Hubbard came along, the influence of Miles Davis had led a lot of trumpeters to opt for an introspective, moody, almost wispy approach to the horn (in many cases a whole lot wispier than Miles, who always had considerable force behind his introspective musings, ever intended). Hubbard's mixture of forward-looking musical ideas and old-fashioned brassiness might be called the essence of the early-sixties Blue Note sound.

That supercharged brassiness is evident immediately here on the opening track, "Philly Mignon," a Hubbard original dedicated to (and made something special by) drummer Philly Joe Jones, a major mover and shaker in the hard-bop movement whose approach is a kind of synthesis of the tidal-wave emotionalism Of Blakey and the more carefully worked out lyricism of Max Roach, with whom Hubbard was to serve an instructive stint in 1965. On "Philly Mignon," Jones and Hubbard urge one another on to almost orgasmic levels of intensity, with Jones playfully chasing Hubbard into the stratosphere and finally getting a chance to dance into the solo spotlight after equally volatile solos by Shorter and Walton. What a bracing way to get things started!

No other track here packs quite the visceral punch of that opener, but there is an underlying power to even the mellower moments. Hubbard himself is so full of energy that even the one ballad on the session, "Body and Soul" — a tune that every jazz artist seems to want to record once, and Hubbard himself was to record again a year later for the Impulse! label — comes out sounding far more affirmative and less sentimental than it usually does.

Shorter, aided in no small part by Jones (who throughout the session plays the Blakey role of keeping the soloists on their toes), is also in a particularly aggressive mood, de-emphasizing the more reflective side of his personality in favor of a hard-hitting stance that is particularly striking on "Full Moon and Empty Arms." That track is also noteworthy for a delightfully sassy solo by Walton, one of the less demonstrative and more reliable pianists in jazz; both Walton and Workman perform their rhythm section roles on Here to Stay with consummate skill and taste.

A word about the writing on this session: Hubbard's other original, "Nostrand and Fulton" (named after an intersection in Brooklyn), shifts into and out of waltz time comfortably. It's a good example of the mixture of sophistication and high spirits that marked the early-sixties Blue Note sound. So are the other two originals, both of them pleasantly exotic in nature without getting self-conscious about it, and both of them the work of trumpeter Cal Massey, whose considerable skills as a composer went virtually unnoticed by everybody except his fellow musicians during his all-too-brief lifetime. (Massey himself had recorded "Father and Son" a year or so earlier as part of a sampler for the Candid label called The Jazz Life.)

Much has happened in Freddie Hubbard's career since this session, including his ascension to crossover stardom in the mid-seventies thanks to a judicious combination of his own talent, heavy backbeats, and electronic gimmickry. But he has managed to maintain the youthful exuberance, as well as the strength, dexterity, and imagination, that first turned heads during his Blue Note years. Almost a quarter of a century after he recorded Here to Stay, the continuing power of Freddie Hubbard's music shows how prophetic that title turned out to be.

— Peter Keepnews

RVG CD Reissue Liner Notes

A NEW LOOK AT HERE TO STAY

Here to Stay is one of those rare Blue Note albums that was heard about long before it was heard. As Peter Keepnews's original liner notes indicate, the music was not released until 1976, when it emerged on a two-record set of the same name (a reissue of Hub Cap was also included), only to resurface on its own more than a decade later. Those who kept up with Blue Note, however, knew the session as one of the elusive holes in the label's 4000 series. As was the case with Tina Brooks's Back to the Tracks, Leo Parker's Rollin' with Leo, and other titles by John Patton, Horace Parlan, and Stanley Turrentine, Here to Stay had been listed (and in some instances pictured) in ads and on the backs of other albums, yet was passed over in favor of other titles at the time of recording.

Some of these delays are explained by the death of the artist (Parker) or an inability to establish an audience for the player in question (Brooks). Hubbard, in contrast, was alive and thriving, so the explanation may have been a combination of (I) too much recorded activity, a situation compounded by (2) the similarly prolific output of Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers, where Hubbard and all of his mates here save Philly Joe Jones were featured at the time, and (3) what appears to have been a brief period in which the trumpeter recorded for two record labels. After cutting his fourth Blue Note album as a leader, Ready for Freddie, in August 1961, the trumpeter led The Artistry of Freddie Hubbard on Impulse! in July 1962, returned to Blue Note for both the October '62 Hub-Tones and the present session, and then went back to Impulse! for sessions in March and May of 1963 that comprised The Body and the Soul. Hubbard's full-time status with Blue Note was reestablished in 1964 with Breaking Point, which featured a working Hubbard quintet with the alto sax and flute of James Spaulding in the front line. Here to Stay remained on the shelf for another decade.

None of this speculation takes away from the quality of the present music, which may lack the ensemble richness of Hubbard's sextet projects of the time or the unique front-line character of the band with Spaulding yet includes memorable playing on a superior program. It goes without saying that all of these musicians were extremely comfortable with each other, including Jones, who was making his third appearance on a Hubbard album. And while there is less original music from within the band than one might expect from a group that includes Wayne Shorter and Cedar Walton as well as Hubbard, the featured material does put everyone in an interesting place between the fresh and the comfortable.

The leader's two contributions are among the less familiar of his celebrated compositional output. The up-tempo "Philly Mignon" is a tribute in the tradition of Tadd Dameron's "Philly J. J." and Kenny Dorham's "Philly Twist," and an ideal setting for Jones's streamlined power. "Nostrand and Fulton" presents a more challenging form with its constant change of meter, a form that Hubbard and fellow brass giant Woody Shaw navigated at an even faster pace when they revisited the composition on their 1987 album The Eternal Triangle. There is also a pair of titles composed by Cal Massey (1928—1972), whose writing was favored by fellow Philadelphians Lee Morgan, Archie Shepp, and McCoy Tyner, as well as Jackie McLean and others. The version of "Father and Son" that Keepnews mentions resurfaced with the remainder of Massey's lone session as a leader, a 1961 Candid date that ultimately emerged as Blues to Coltrane, where it was revealed that Cal's son, Zane Massey, had tapped the melody out on a drum kit. In his adult years, Zane emerged as a saxophonist, and he recorded "Assunta" on soprano sax for his 1992 disc Brass Knuckles (Delmark). The original version of "Assunta" is found on trumpeter Bill Hardman's 1961 Savoy album Saying Something, where the melody yields to a fast 4/4 modal structure for the solos.

This version of "Body and Soul," which introduced what would become a trademark harmonic substitution at bar four, should also be heard in the context of a Shorter septet arrangement on The Body and the Soul, where Eric Dolphy's flute adds a memorable counterline. The venerable ballad would later become central to Hubbard's performing repertory, where (as can be heard on the 1981 Fantasy album Keystone Bop) he would put on the audience by prefacing the chorus with the verse from "Stardust.'

— Bob Blumenthal, 2006

No comments:

Post a Comment