Andrew Hill - Smokestack

Released - September 1964

Recording and Session Information

Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, December 13, 1963

Andrew Hill, piano; Richard Davis, bass; Eddie Khan, bass #1-4,6,7; Roy Haynes, drums.

tk.6 Smokestack

tk.9 Wailing Wall

tk.11 Ode To Von

tk.16 The Day After

tk.21 Verne

tk.23 Not So

tk.24 30 Pier Avenue

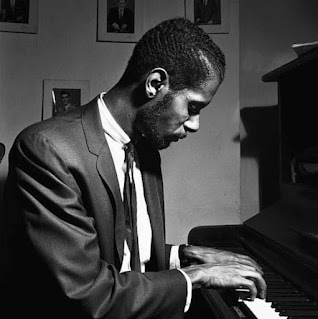

Session Photos

|

| Duke Pearson at rehearsal |

Photos: Francis Wolff

Track Listing

| Side One | ||

| Title | Author | Recording Date |

| Smoke Stack | Andrew Hill | 13 December 1963 |

| The Day After | Andrew Hill | 13 December 1963 |

| Wailing Wall | Andrew Hill | 13 December 1963 |

| Ode to Von | Andrew Hill | 13 December 1963 |

| Side Two | ||

| Not So | Andrew Hill | 13 December 1963 |

| Verne | Andrew Hill | 13 December 1963 |

| 30 Pier Avenue | Andrew Hill | 13 December 1963 |

Liner Notes

The jazz piano of the late 'fifties and early 'sixties reached its fullest expression in the work of three influential players - Thelonious Monk, Bill Evans and Cecil Taylor. Monk worked out a remarkably successful interrelationship between spaces and sounds, pitch ranges and metric accents, that bypassed the limitations of harmonic cadence rhythms. Evans used modal scales as starting points, sometimes superimposing them over relatively ordinary harmonic sequences, occasionally using them as an improvisational basis in themselves. By permitting his bassist to roam freely in and out of the piano textures - the drummer meanwhile providing the basic metric pulse - Evans produces music of great rhythmic and harmonic mobility. Taylor used massive tonal complexes that, by their very density, overcame harmonic restrictions. Like Evans (and John Coltrane as well) Taylor has worked out an intricate relationship with rhythm sections (especially with drummer Sonny Murray) which avoids a continuously pulsating metric time.

Andrew Hill is heir and descendent of Monk, Evans and Taylor (as well as of such basic influences as Bud Powell and Art Tatum). Surprisingly, for a young player who has only recently come to the attention of the wide jazz audience, Hill has already made a remarkably personal distillation of these influences, added a significant measure of his own ideas and emerged with one of the strongest, most persuasive playing styles in contemporary jazz. Sometimes lyrical, sometimes percussively dramatic, sometimes drawing from his excellent understanding of his predecessors, Hill is the model of a gifted young creative artist.

He is accompanied in this set by bassist Richard Davis (also a participant in Hill’s other Blue Note dates), a second bassist, Eddie Khan, and drummer Roy Haynes. Davis, of course, has become one of the most dependable and consistently inventive jazz bassists. His activities run the gamut of the New York professional music scene, but his most stunning work seems to come forth in dates with players of the caliber of Hill and the late Eric Dolphy. The requirements of this particular session created a number of special problems. Two basses, for example, can produce a startling rhythmic impact, but they can also produce a texture so muddy and turgid as to prevent any swing. It is to the credit of both Davis and Khan that the latter possibility did not take place and the former did. Khan’s role is not so dramatic as Davis’, since he usually plays a modestly understated pulse, but his interaction with Davis and with Haynes’ percussion is an extremely important (if subtle) factor in the success of this recording. In his one solo effort (on 30 Pier Avenue) Khan’s credentials as a thoroughly modern player are self evident. Haynes continues to roll along; today, as through his active playing career, his work is a model of what sensitive drumming can and should be.

The tracks included in this collection were made at Hill’s second session for Blue Note in December 1963. As documents in his rapidly burgeoning artistic growth, they are invaluable. But more than that, they offer especially provocative insights into a creative direction which differs somewhat from that of Hill’s subsequent Blue Note sessions. The choice of two basses was made in the hope of providing the increased complexity - with the cross-rhythms, resultant rhythms and just plain rhythmic densities - that two such instruments in tandem can provide. The wisdom of this choice is amply confirmed in the title tune, Smoke Stack, in which the rhythmic stream becomes so filled with cross-currents and eddies that the basic meter becomes nearly unrecognizable. Notice, too, the unusual effect produced in Wailing 17 all by Haynes’ cymbal accents juxtaposed against Hill’s rhapsodic accompaniment figures. The most prominent feature, however, is Richard Davis’ voice - like bowed bass solo - a long declamatory line that moves sensuously in and out of semitone and microtone changes of pitch.

Davis also plays superbly on Verne, the only trio track (with only one bass). Haynes, often acclaimed for his brush work, fully justifies the compliments. Hill’s piano line is a fine example of ornamentation technique that still retains the subliminal qualities of the original melody. On 30 Pier Avenue Hill’s playing illustrates his fine technical abilities; everything from ringing block chords to fleet single-note lines and thick, ringing clusters is explored. Ode To Von and Not So, medium tempoed swingers (although the rhythmic cross-currents make specific tempo descriptions difficult) offer a few open spots for Haynes. He fills them with typically well-conceived, economical expressions. On The Day After, Hill’s ballad-like line is considerably modified by the contrasting bass rhythms, especially Davis’ crystal-clear, penetrating high note accents. Again, too, Davis’ exceptional pizzicato technique is little short of amazing.

As many observers are slowly discovering, the new generation of post-bop players is not nearly so single-mindedly nihilistic as some listeners thought four or five years ago. The new jazz, in fact, is considerably more heterogeneous than the music which immediately preceded it. Most jazz players, thankfully, continue to ignore their critics and exhibit the qualities of individualism and personal motivation that have made their work so rewarding in the past. The fact that new materials, structures and procedures are being explored in no way alters this fact. The solutions that Ornette Coleman has found to the problems of contemporary improvisation are vastly different from those found by Eric Dolphy. But in their search for answers both players found playing styles that are, for the discerning listener, vastly rewarding.

Andrew Hill’s playing style is distinctly his own, but it is nevertheless intimately involved in the solution of musical problems which are In the mainstream of contemporary jazz. Some of his unique and fascinating answers to these problems are provided here.

- DON HECKMAN

RVG CD Reissue Liner Notes

A NEW LOOK AT SMOKE STACK

Don Heckman states quite clearly that Smoke Stack was Andrew Hill's second visit to Rudy Van Gelder's Studios for Blue Note. What could go without saying, given the pictures of previous issues that accompanied Heckman's notes on the back of the original LP, was that it was the fourth Hill album to be issued. Those numbers suggest how challenging the music included here sounded — then and now — as well as to the priority the pianist assigned to this music among the voluminous body of original compositions he brought to the label.

Producer Alfred Lion had clearly been excited by Hill, hearing in his playing and composing a deep and original concept akin to those of previous Blue Note discoveries, Thelonious Monk and Herbie Nichols. Yet Lion must have sensed that this particular quartet playing these seven originals would pose a challenge that listeners might feel unprepared to accept on the basis of his only previous effort, the iconoclastic though far more conventional quartet session Black Fire with Davis, Haynes, and Joe Henderson, taped only a month earlier. So Hill was brought back a mere month after Smoke Stack for Judgment!, with the same rhythm section plus Bobby Hutcherson. Perhaps the magnificence of Hill's next effort, the sextet Point of Departure from March '64, would have delayed any of the pianist's unreleased music. The fact that Hill chose to document the present configuration of piano, two basses, and drums so quickly in his recording career confirms the importance he placed in both the unusual setting and the music he crafted for it.

Employing two basses in a rhythm section had been used on previous occasions, most notably by John Coltrane and Ornette Coleman, although Hill's approach to the challenge differed in that he did not really hear his bassists as two equal voices. This is why Smoke Stack cannot be fully understood if viewed as one of three Hill albums with the Davis/Haynes rhythm section. With the exception of "Verne/' where Eddie Khan lays out, Davis is in truth more the second featured voice, one that — given the tonal and textural mesh of piano and bass — could assume a more constant and interactive role in a quartet setting than Henderson's tenor or Hutcherson's vibes.

The wizardly Davis fills this part to perfection, stressing the ambiguous edges Of what at this stage remained odd but still defined structures. Khan is the accompanist here, and goes about his business in a self-effacing way. (One can only wonder what magic might have arisen it a third Chicagoan, Wilbur Ware, had joined Hill and Davis in this effort,) Khan met a number of musical challenges in recordings of the period with Henderson, Freddie Hubbard, Jackie McLean, and Max Roach, and shows his own exploratory bent in solos on "30 Pier Avenue" and (contrary to Heckman but according to Lion's session notes) "Ode to Von."

Roy Haynes is perfect for the combustible control that this music evokes, he is constantly elaborating the beat without losing it, and his own tonal/textural mesh of emphatic snare, tom-tom, and cymbal figures creates a brilliant balance of its own with the perpetual thickening and thinning, rising and falling of Hill's piano. The piano/drum exchanges on both takes of "Ode to Von" ate among the best examples of a piano/drum partnership that deserves reviving.

Adding to the unusual sound of the two-bass quartet is the unpredictable nature of Hill's compositions. When Mosaic Records issued a boxed set of Hill's work in 1995, producer Michael Cuscuna had the foresight to enlist Bob Belden in helping to decipher Hill's schemes. "Belden can transcribe most music (not Andrew's, though) in real time," Cuscuna reported, and what Belden discovered in this instance was a 50-bar title tune and a 22-bar " Not So," among other challenging if less asymmetric offerings. Given the way Hill develops thematic kernels, both within the written line and in his improvisations, a surface coherence is sustained that takes the listener along the unusual choruses in surprising comfort.

Each of the four alternate takes (which first appeared in 1995) was considered for release on the original LP. The alternate "Smoke Stack" opened the session and contains a shorter piano solo. The master of "Ode to Von" (for Von Freeman, still unknown outside Chicago at the time) preceded the alternate and receives a more combustible performance, while the master of "The Day After" came first and seems more settled. The influence of Monk is most clearly felt on the master of "Not So," cut after the alternate. Finally, the trio piece "Verne" is named for Hill's first wife, the late organist Laverne Gillette.

— Bob Blumenthal, 2005

No comments:

Post a Comment