Stanley Turrentine - Hustlin'

Released - March 1965

Recording and Session Information

Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, January 24, 1964

Stanley Turrentine, tenor sax; Shirley Scott, organ; Kenny Burrell, guitar; Bob Cranshaw, bass; Otis Finch, drums.

1286 tk.3 Something Happens To Me

1287 tk.8 The Hustler

1288 tk.9 Love Letters

1289 tk.24 Goin' Home

1290 tk.26 Lady Fingers

1291 tk.28 Trouble (No. 2)

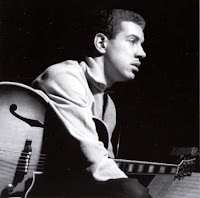

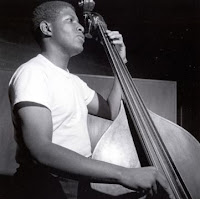

Session Photos

Photos: © Francis Wolff/Mosaic Images

https://www.mosaicrecordsimages.com/

Track Listing

| Side One | ||

| Title | Author | Recording Date |

| Trouble (No 2) | Logan, Price | 24 January 1964 |

| Love Letters | Segal, Fischer | 24 January 1964 |

| The Hustler | Stanley Turrentine | 24 January 1964 |

| Side Two | ||

| Ladyfingers | Shirley Scott | 24 January 1964 |

| Something Happens to Me | Heyman, Young | 24 January 1964 |

| Goin' Home | Dvorak | 24 January 1964 |

Liner Notes

Down through the years there have been a number of illustrious husband and wife teams in jazz. One of the first and most famous was Louis and Lil Armstrong. Then there was vibist Red Norvo and his singer spouse, Mildred Bailey. Pianist Mary Lou Williams twice combined music and matrimony during her career; first with alto saxophonist John Williams, and later with trumpeter Shorty Baker. Clarinetist Joe Marsala's harpist was his wife, Adele Girard.

Trumpeter Joe Guy backed Billie Holiday's performances during the time they were married. In the period bassist Roy Brown was wed to Ella Fitzgerald, he led the trio which accompanied her.

These are some of the more prominent wedded wailers in jazz history. Relevancy does not dictate naming all the married couples who have graced jazz, but as it stands, this is a varied, impressive list. The most recent addition is the very active twosome of Stanley Turrentine and Shirley Scott. Stanley first attracted attention in Max Roach's group; Shirley gained recognition in a combo with tenor man Eddie "Lockiaw" Davis. in the '60s they joined musically, and followed by becoming man and wife. If their performance since then can be used as yardstick, it certainly indicates a strong argument in favor at wedded bliss. Of course, the rapport that the two had from the beginning, which led to the even closer alliance, has been further strengthened in a circle that is anything but vicious.

Both Stanley and Shirley have a great deal of warmth in their playing and they complement each other well. This is especially evident in this set where things are groovy and never strident. Kenny Burrell, one of the premier guitarists in jazz, adds his controlled fire to the proceedings and proves to be a welcome guest in the Turrentine household.

Bass and drums are in good hands. Bob Cranshaw is a powerful, straight-ahead player who has been heard to advantage with Sonny Rollins, Carmen McRae, and on several recent Blue Note recordings. Otis ”Candy" Finch was a member of the wonderful small band that Billy Mitchell and Al Grey co-led a few years back. Everyone knows that a band is only as good as the sum of its parts, and Finch was a very important part of the well-oiled machinery.

Trouble, by Lloyd Price, was first done by the Turrentines in Never Let Me Go (Blue Note 4129). This is their second version, hence Trouble #2. It’s the blues - the rhythm and blues blues. Stan is hootin’ and hollerin’ as the group churns up a blue loam under him. Shirley does some crying (some wailing too) about trouble with Burrell punctuating and Finch keeping the rolling backbeat in motion. Like Stan, she reaches a peak and then lets you down easy. You are left with the feeling that this is trouble that can be surmounted.

Love Letters are something that S&S don't have to write to each other; they can play them instead. These envelopes are full of tender thoughts, stated in a casually swinging script. Stanley’s gorgeous tone - masculine but not harsh - is heard to advantage in this Victor Young song, as Shirley comps with empathy before demonstrating her inventive right-hand solo lines. Burrell floats along in keeping with the previously established mood. Turrentine's lead voice then seals the flap and stamps the letter.

The blues are back in The Hustler by Turrentine. This time they are in a minor key with Kenny’s azure guitar leading off the solos with a combination of earth and sophistication. Stanley sidles in to cook convincingly in his non-hysterical manner. When the fire comes from within, you don’t have to flail about to communicate. Shirley’s short stint caps the solo section and leads directly to the theme.

Ladyfingers, by Shirley, is a blues waltz that pulses along with a compelling beat. After Burrell solos, the fingers of that talented lady, Shirley Scott, take over the spotlight. Turrentine is third with an effort that brings the whole performance to a climax.

A ballad by Marvin Fisher and Jack Segal, Something Happens To Me, is given a swinging treatment that does not neglect its lovely melody. Stanley, Kenny, and Shirley make good use of the opportunities for buoyant, happy playing that the chord structure and the rhythm section afford. Finch is a more than able propeller.

In the 1890s, the Czechoslovakian composer, Antonin Dvorak, spent three years in New York. His New World Symphony in E minor was a result of this visit. From the second movement (Largo) come the theme which become known as Going Home. Dvorak's original inspiration supposedly was the poem by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, entitled Hiawatha's Wooing. Turrentine effectively woos the melody with swing, yet he retains the touch of melancholy that was inherent in the music’s first form. Burrell spins out a relaxed solo, and Mrs. Turrentine finishes with a chorus that literally sings before Stanley returns to take everyone home.

A home is not necessarily a house, especially when it's a bandstand. This is where Stanley Turrentine and Shirley Scott have chosen to set up light housekeeping. Their music is not something to be taken lightly, however.

What comes forth from an instrument is supposed to be indicative of what that instrument’s player is feeling. If this is true, Stanley and Shirley are one of the most happily married couples going, in or out of jazz.

RVG CD Reissue Liner Notes

A NEW LOOK AT HUSTLIN'

After the Adderley Brothers, Stanley Turrentine and Shirley Scott represent the most prominent and prolific example of family teamwork in 1960s jazz. The saxophonist and organist were married during those years, and built upon the reputations each had established independently as recording artists prior to their union. During a stretch of slightly more than seven years between 1961 and '68, Turrentine and Scott documented their partnership frequently on Scott albums for Prestige, Impulse! and Atlantic, and on several of Turrentine's Blue Note sessions as well as his Ione Impulse! release. The beginning of their shared discography in June 1961 saw attempts to get around respective contractual conflicts, with a Stan Turner taking sax credits on Scott's Prestige album Hip Soul while Turrentine's Dearly Beloved on Blue Note featured organist Little Miss Cott. No one was fooled in either instance, and the half-hearted subterfuge was abandoned on subsequent albums.

While they toured as a unit throughout the decade, both Turrentine and Scott liked variety in their recording projects. For his part, Turrentine only designed five of his Blue Note sessions around Scott, which is not even a third of his output for the label. Three of the five were produced in the year that separates the February 1963 Never Let Me Go (Scott's first Blue Note credit under her own name) and the present session. Each Turrentine date with Scott has its own distinct feeling thanks to adjustments in instrumentation, though it is worth emphasizing that most of their recorded encounters include a bassist. We tend to think of the "classic!' organ/tenor configuration as a quartet completed by guitar and drums, like the Jimmy Smith recording units on Midnight Special and Back At The Chicken Shack that marked Turrentine's debut on Blue Note. Of course, one thing that made Smith incredible is that he never used a bassist and always supplied his own bass lines. (He never carried a horn in his working band of the time, either.)

Scott generally worked with a bass and without guitar when recording under her own name, on the Eddie "Lockjaw" Davis Prestige sessions that initially established her reputation, and in her partnership with Turrentine. She contributes intriguing bass lines on Dearly Beloved, a rare tenor/organ/drums date in Scott's discography; but the pianistic clarity she achieved through her personalized settings of the organ stops is heard to better advantage when an acoustic bass is holding down the bottom, as Bob Cranshaw does here.

Where Ray Barretto's conga drums were employed on Never Let Me Go, and Blue Mitchell's trumpet graced Turrentine's next album with Scott, A Chip Off The Old Block from October '63, the added starter here is Kenny Burrell. The saxophonist and guitarist had first demonstrated compatibility on the aforementioned Jimmy Smith albums, and on such other memorable occasions as Burrell's Midnight Blue, and the guitarist is once again an ideal collaborator here. He is both modern enough to flow through the chords of the pop songs and soulful enough to sustain the mood of the blues titles; his supple guitar is a fine complement to Scott's organ sound; and he accompanies with shifting figures that add a quiet charge to the background, In this last regard, note "Trouble (No.2)," where Burrell's supporting work stays out of a fixed pocket and leads Scott into some surprising responses.

Few players in the modern mainstream had Turrentine's gift for assembling programs including both arcane tune choices and the down-to-earth lines that the last Turrentine/Scott session for Blue Note (from August 1968) referred to as his Common Touch. This second "Trouble" has a different, hard-shuffling feeling than the version contained on "Never Let Me Go," where Barretto played tambourine. It is from the book of popular vocalist Lloyd Price, whose band's up-tempo instrumental version of "Misty" was the basis for another successful jazz cover by organist Richard "Groove" Holmes. It provides a touch of gospel that effectively contrast the no-nonsense minor blues "The Hustler" and the airier blues waltz "Ladyfingers." The traditional African-American melody "Goin' Home," which Dvoråk had adapted for his famous symphonic work after a visit to the U.S., adds another distinct blues flavor that the band addresses with dignity rather than false fervor.

There is also great dignity in the two remaining selections, especially when Turrentine plays the melody choruses. Stating a theme without undue distortion and still getting your own personality across is a mark of distinction for any jazz soloist of era. The way Turrentine plays "Love Letters" and "Something Happens to Me" lets us know, even without hearing the lyrics, exactly what these songs mean, and also announces that we are in the presence of a true master.

— Bob Blumenthal, 2002

No comments:

Post a Comment