Grant Green - Street Of Dreams

Released - August 1967

Recording and Session Information

Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, November 16, 1964

Bobby Hutcherson, vibes; Larry Young, organ; Grant Green, guitar; Elvin Jones, drums.

1469 tk.5 Lazy Afternoon

1470 tk.8 I Wish You Love

1471 tk.12 Somewhere In The Night

1473 tk.26 Street Of Dreams

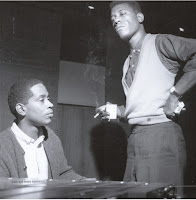

Session Photos

Photos: Francis Wolff

Track Listing

| Side One | ||

| Title | Author | Recording Date |

| I Wish You Love | Chauliac, Trenet | November 19 1964 |

| Lazy Afternoon | Latouche, Moross | November 19 1964 |

| Side Two | ||

| Street of Dreams | Young, Lewis | November 19 1964 |

| Somewhere in the Night | Billy May, Milt Raskin | November 19 1964 |

Liner Notes

"Guitar and organ go well together," Grant Green said in an interview not long after he arrived in New York a few years ago. "My favorite trio is guitar, bass, and drums. You can really stretch out, and nothing gets cluttered up."

This album offers what might be called the best of worlds. Green has with him his favorite trio — identical in personnel to the one in which he was featured on the Talkin' About album. But in addition to Larry Young and Elvin Jones, he has the uniquely powerful assistance of a musician who contributed memorably to a somewhat earlier Green set, Bobby Hutcherson of Idle Moments fame.

In the past few years Hutcherson has earned an increasingly close identification with the new wave; as his work on various Blue Note undertakings with Andrew Hill, Grachan Moncur III, and others has indicated, his ears are wide open to the freest of sounds. Yet his partnership with Green, a soloist more closely rooted to melody in the traditional sense and also of course very durably linked with the blues, works out well for both because of Bobby's adaptability and because Of the obvious mutual respect of the two for each other's musicianship.

"Grant is an exceptional musician," says Hutcherson. "I like the full, singing sound he gets from the instrument, and he doesn't ever play clichés. He's a real improviser who knows how to extend his ideas, and I like him better than a couple of others who are perhaps more famous but aren't really saying as much."

Larry Young is ideally equipped to work both with Grant and with Bobby, for although he has a background of experience in rhythm and blues bands, his interests also stretch to the end of the spectrum that includes Coltrane and McCoy Tyner. "Larry is one organist who can be counted on not to do the obvious," comments Hutcherson. "He started out as a piano player, and you can sense this in his very musical approach to the organ."

Elvin Jones's presence need only be explained to those who have not followed his career too closely. That he can do anything that is needed and exercise whatever restraint may be required will come as no shock to those who have heard him in numerous Other unpretentious settings. When he took part in the I Want to Hold Your Hand album with Grant, Larry Young, and Hank Mobley, Dan Morgenstern of Down Beat was moved to comment: "Jones's playing in this album may surprise those only accustomed to his work with John Coltrane. If so, they haven't realized that Elvin Jones is a complete musician, who can adapt to any valid musical environment."

The opening track is a popular song, "I Wish You Love," associated in the with Gloria Lynne, Keely Smith, and Other singers. After Larry's mood-setting introduction, Grant takes over to play the verse, which has always been an important part of the tune, and which he plays in an unconventional style, doubling the number of bars and adding a gentle touch Of Latin rhythm in the background.

Here, as on all the tracks in this gently persuasive set, one is conscious of the effectiveness of this instrumentation. Until the past year or two, vibes players have been a comparative rarity in guitar-organ combos, yet their use, in background and solo capacities alike, can do as much for a low-key mood as the tenor saxophone can for the more extrovert brand of performance.

In effect, Grant performs three different functions in the first half of this track. As noted, he plays the verse, which is a brooding, minor-mode theme; Second, he moves along to the major melody of the chorus, altering its lines only slightly and subtly; then comes the third assignment, the blowing passage, and it is here that he builds to a peak — not of excitement, for that is not the objective, but of intensity and inspiration.

Obviously there has to be at least a touch of Charlie Christian in every contemporary guitarist, and as I listened to Grant in his supremely confident improvisational passages here, the thought came to mind that had Christian ever recorded any numbers with a Latin rhythm background, this is probably just about the way he would have sounded.

"Lazy Afternoon," also mainly known as a vocal vehicle rather than a jazz instrumental, was first popular in the early 1950s. As we hear it done up Green in this most unconventional treatment, the entire work shifts gear as Grant puts it in 5/4 time. Applied to a melody already well known in the standard 4/4, this can sometimes smack of a gimmick, yet Grant's ingenious adjustment of the main phrasing of the melody makes it seem like the most natural thing in the world.

Larry helps to establish a comfortable setting for this meter as he places accents on the second, third, and fifth beat of the measure. Bobby's solo follows the leader's, spare and graceful, making the five feel swing in an elegant fashion, before Grant returns to bring back the theme.

"Street Of Dreams," a melody by the late Victor Young, is probably the best-established (in jazz circles, anyway) of the four tunes in this set, as well as the oldest. The street is paved with golden solos as Grant, Bobby, and Larry take their turns. Here there is no Latin rhythmic addition, no change of meter — just a straight-ahead rendition that swings in the orthodox four. The organ solo, though never excessively busy or repetitious, builds in intensity until Grant takes over in a style that follows very logically and keeps up the established momentum. Notice Grant's various ingenious uses of triplets at several points during his blowing passage.

"Somewhere in the Night," also known to television viewers some seven or eight years ago as The Naked City theme, was first popularized by jazz singer Teri Thornton. Grant and Bobby combine winningly as they introduce the melody in unison. As in the preceding track, the tempo is moderate and the beat a steady four, with Elvin a sturdy guiding force throughout.

Bobby Hutcherson offers an especially convincing demonstration here of his facility in an idiom that might best be characterized as pre-avant-garde-contemporary. Larry makes beguiling use of the attractive changes that are the meat of this theme. Grant, as usual, is fluency personified all the way through to the faintly Diango Reinhardt-ish closing cadenza.

At this writing, the four men featured on these sides are all going their separate ways, Bobby as a sideman with John Handy and the other three mainly as leaders of their own groups. But it is safe to assume that they all recall with special pleasure this easy-going, informal session for which Alfred Lion called them together. The music they made reflects their mood on that particular day: a mood of contemplation blended with inspiration, of cooking on a slow burner. Given these ingredients and men of this caliber, it would be hard to go wrong.

— Leonard Feather

RVG CD Reissue Liner Notes

A NEW LOOK AT STREET OF DREAMS

Over the course of his years with Blue Note, Grant Green enjoyed sustained relationships with a number of memorable rhythm sections. Without question, he was most prolific in the company of organist John Patton and drummer Ben Dixon, who are heard with the guitarist on over a dozen sessions taped between 1962 and '67. Other units, while more fleeting, were equally memorable: Dixon and organist Baby Face Willette (1961), pianist Sonny Clark and bassist Sam Jones (with Louis Hayes and, on one occasion, Art Blakey on drums, 1961—62), and the Larry Young/Elvin Jones pairing heard on the present tracks.

Placing Green alongside John Coltrane's drummer and the man who Jack McDuff once described as "the Coltrane of the organ" was clearly a change of pace for the guitarist. Green and Jones had a history, however, dating back to Green's first jazz recording with Jimmy Forrest in 1959, and renewed in the spring of 1964 on sessions that produced the Green albums Matador and Solid. Both of those dates remained unissued for years, however, so that Green's encounter with Jones and the little-known Young on the September '64 Talkin' About session caught many of the guitarist's fans off guard. Without sacrificing the deep-blue feeling that had made him so popular, Green was now conversing with two of the period's most daring artists. The connection among the three was strong enough to win the organist his own Blue Note contract, which was launched with Green, Jones, and Sam Rivers two months later on Young's Into Somethin'. Four days after that one, the trio returned to Rudy Van Gelder's with a new fourth voice.

Pairing vibes and organ in a jazz context went back at least to Lionel Hampton and Milt Buckner, and had gained more contemporary currency on albums by organist Johnny "Hammond" Smith and vibist Johnny Lytle at the time Street of Dreams was created. Still, the choice of Bobby Hutcherson sets this organ/vibes encounter apart, much as the Green/Young/Jones unit was set apart from the conventional organ combo. Hutcherson was one of Blue Note's new voices (though not one of its leaders for another five months), and had no trouble meshing with Young's sonic and harmonic notions or Jones's polyrhythms. In addition, Hutcherson had total command of more mainstream concepts and settings, as proven unequivocally in his previous meeting with Green, Idle Moments. There was probably no other living vibes player who could have fit as well into this particular group.

The more common question for those who have never heard this or the other Green/Young/Jones sessions is how Grant Green would fare in the company of such firebrands. Quite brilliantly, as it turns out, because for all the seeming simplicity in his approach, Green was quite sophisticated when it came to choosing material. From the outset of his recording career, he had demonstrated a preference for programs that featured strong and distinctive song structures in quantity. (This is perhaps the clearest sign that Charlie Parker, rather than any other guitarist, was indeed Green's primary influence.) Any one of the four songs heard here might have served as the ballad feature on a typical jazz album of the period; but they probably would have been surrounded by a heavy dose of tracks employing blues structure or "Rhythm" changes. This program of extended improvisations on themes with substantial and uncommon harmonic meat was unique to begin with; and Green's song choices, all bittersweet in their way, give a further uncommon spin to the date, combining probity, chops, and mood in a blend all its own. While each track is strong, "Lazy Afternoon" stands out for its effective transformation into 5/4 tempo, while "Somewhere in the Night" remains all too rare (though this writer heard Hutcherson deliver a scorching version in the company of Jackie McLean at the turn of the millennium).

Green made one more album with Young and Jones, the March 1965 I Want to Hold Your Hand (with Hank Mobley on tenor saxophone), and the trio is known to have worked club dates briefly in New York. Then Green left Blue Note and his career took a more commercial turn, while Young and Jones remained together on the organist's masterpiece, Unity, recorded in November 1965 with Woody Shaw and Joe Henderson. That album is widely considered one of the decade's classics, yet the earlier efforts of Young, Jones, and Green remain curious footnotes at best for too many listeners. Here is one of four proofs that, before recording the organist's masterpiece, Larry Young and Elvin Jones enjoyed another kind of unity.

— Bob Blumenthal, 2008

No comments:

Post a Comment