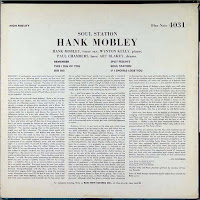

Hank Mobley - Soul Station

Released - August 1960

Recording and Session Information

Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, February 7, 1960

Hank Mobley, tenor sax; Wynton Kelly, piano; Paul Chambers, bass; Art Blakey, drums.

tk.3 Remember

tk.4 Split Feelin's

tk.12 Dig Dis

tk.18 This I Dig Of You

tk.20 Soul Station

tk.25 If I Should Lose You

Session Photos

Photos: Francis Wolff/Mosaic Images /

Track Listing

| Side One | ||

| Title | Author | Recording Date |

| Remember | Irving Berlin | 07/02/1960 |

| This I Dig of You | Hank Mobley | 07/02/1960 |

| Dig Dis | Hank Mobley | 07/02/1960 |

| Side Two | ||

| Split Feelin's | Hank Mobley | 07/02/1960 |

| Soul Station | Hank Mobley | 07/02/1960 |

| If I Should Lose You | Ralph Rainger, Leo Robin | 07/02/1960 |

Recently, it has become more and more incorrect to pass off a jazz record as a "blowing date" (a term, by the way, that has become at least semi-derogatory) simply because there are only four or five musicians involved. The days of men coming into a studio and "just blowing" (a practice that only the very greatest jazzmen have ever been able to get away with) are apparently over, for the most part. At one time, you could safely assume that a forty-minute LP had taken, at most, an hour to put together. No more.

What has this to do with Hank Mobley? Quite a bit, to judge from this IP, Soul Station. On the surface, it contains all the elements of a blowing session - tenor '. and rhythm, a few originals, a couple of seldom-done standards, and a blues. But the difference is to be heard as soon as you begin to listen to the record. And let us take things in what might seem to be reverse order for a moment, and discuss the reasons for the difference itself Hank has always been a musician's musician - a designation that can easily become the kiss of death for the man who holds it. Fans and critics will reel off their list of tenor players, a list that is as easily changed by fashion as not, and then the musician over in the corner will say, "Yes, but have you heard Hank Mobley?" The musician saying that, in this particular case, might very well be a drummer. The groups Hank works with are often led by drummers - Art Blakey and Max Roach, to name two men who need, as they say, no introduction, and the first of whom contributes to a great degree to the success of this album. One might suppose, considering this, that Hank is possessed of an unusual rhythmic sense, and one would be right. In a conversation I had with Art Blakey while preparing the notes for his two Blue Note LPs called Holiday For Skins (BLP 4004-4005), he was discussing the fact that while many songs are written in complex rhythms, the solos generally revert to a straight four. His reason for this was that most soloists probably could not play them any other way. "Hank Mobley could do it, though," he said. But even while possessing this definite asset. Hank has also carried a liability around with him for a long time - a liability, that is, as far as commercialism is concerned: he is not easily classified. Everyone knows by now how writers on jazz like to trot out phrases like Hawkins-informed, Rollins derived, Young - influenced and the like, and then, having formed their pigeonhole, they proceed to drop the musician under discussion into it and fill the dirt in over him. That is not easily done with Hank Mobley. He is, to be sure, associated with East Coast musicians and material, but he has never had the so-called "hard bop" sound that is generally a standard part of the equipment of such tenormen. At the same time, Charlie Parker was certainly a greater part of his playing than Lester Young, which is often enough to label a man a bopper, so what was Mobley doing? The answer is so simple as to be completely overlooked in a mass of theory, digging for influences, and the like: he was working out his own style.

But - and here again, he suffers from a commercial liability - he did not do it in a spectacular way. He did not, in the manner of Sonny Rollins, in 1955 emerge from a long self-imposed retirement with a startling new approach. Nor did he, in the manner of John Coltrane, come almost completely unknown under the teaching influence of the great Miles Davis (for how many men has that recently been the key to success). Instead, he worked slowly and carefully, in the manner of a craftsman, building the foundations of a style, taking what he needed to take from whomever he needed to take it (everyone does that, the difference between genius and hackwork is the manner in which it is done), and finally emerging, on this album, not with a disconnected series of tunes, but with a definite statement to make.

Evidence of that, to get back to the idea with which these comments began, is to be found in the care with which this set has been assembled. First of all, there are the sidemen - Wynton Kelly, Paul Chambers and Art Blakey. To discuss Blakey again on each new record release is almost to insult him and his contribution to jazz, particularly since he says it himself very well, clearly, and with great authority in his solo on "This I Dig Of You."

But about Wynton Kelly and Paul Chambers, for a moment. It is probably no accident that both of them are members of Miles Davis's group - I hesitate to call it a quintet or sextet, since that is so often in doubt. Miles has been famous for the superb quality of his rhythm sections as much as for any of his other contributions, and some of the ideas that started in his group or in his observance of Ahmad Jahmal's group are to be found on this record. The basis of these ideas - pedalpoint, rhythmic suspensions, a general lightness of approach - all have their basis in one underlying idea - the best music is never very far from dance. This concept can be found not only in Miles's work, but in the solo albums made by Coltrane, in those of Sonny Rollins, and even in the work of Thelonious Monk, who has taken to doing his. own extremely expressive dance in front of his group. This is not to say that any of these men, or Hank Mobley either, "play for dancing," although what they play is certainly more conducive to dancing than the music of Freddy Martin or Guy Lombardo, but that the qualities that are essential to dance - a light- ness, flow and flexibility, all within the confines of definite form and overall sense of structure - are essential to their music.

The unusual sound of Mobley's tenor might very well come of this idea of dance. Jazz is rich in legends of unknown saxophonists, celebrated only in their immediate area, but having an enormous effect on men who went on to much wider acclaim. These men being small-town on-the-stand musicians, playing for dances for the most part, have had in all likelihood, a sound very much like the sound of Mobley's tenor, or like Coltrane's or Rollins's, for that matter. And it would take a man with a knowledge of dance music to pick as fine and unlikely an old song as Irving Berlin's "Remember" to start his set with. (Monk, incidentally, also has a penchant for old Berlin tunes.)

I think also, that dance must be behind as charming, lightly swinging, and immediately attractive a song (song is the right word here, not "tune" or "original") as Hank Mobley's composition "This I Dig Of You," which brings out the best of all the musicians - Blakey's solo has been mentioned before, and I am particularly charmed by Wynton Kelly's solo, with its ever-present echoes of 'The Party's Over."

These ideas are present, but the four men involved are all excellent craftsmen, so the ideas do not intrude upon the music, as sometimes happens with the sometimes over-selfconscious Modern Jazz Quartet. You do not think of dance, or rhythmic shifts, or the changing approach to the tenor saxophone, or the old tunes, or the inevitable funky blues. You simply hear, at first, four men swinging lightly, powerfully and with great assurance and authority. You relax, listen and enjoy yourself. And then later, when you think about it, you realize just how much of an achievement this apparently causal LP represents. And you think with new admiration and respect about Hank Mobley, because you realize how much of that achievement he has been able to make his own.

- JOE GOLDBERG

Cover Photo by FRANCIS WOLFF

Cover Design by REID MILES

Recording by RUDY VAN GELDER

RVG CD Reissue Liner Notes

NEW LOOK AT SOUL STATION

The subtle joys of this album, which Joe Goldberg celebrates so astutely in his liner notes, did not go unnoticed by commentators at the time Soul Station was released in 1960. It was hailed as Mobley's finest session, an opinion that has become generally accepted in the succeeding decades. Still, Mobley remained something of a second echelon figure in the jazz world. At a time when Sonny Rollins had mysteriously withdrawn from the scene, John Coltrane had finally formed his own working band and Ornette Coleman was introducing his revolutionary concepts in the clubs of New York, Mobley's kind of saxophone playing simply did not seem epochal enough. Good as it was, it would not change the world.

The slow and steady reevaluation of Mobley, with Soul Station generally cited as exhibit A by those who treasure his music, has led to a greater appreciation of not only this album but also those he made before and since. With this longer view of his collected work, the bulk of which appeared on the Blue Note label, we can recognize that this album announced the second and most consistently satisfying phase in Mobley's career. After a prolific stretch of performing and recording between late 1954 and early 1958, when Mobley had worked with the bands of Max Roach, Dizzy Gillespie, the original Jazz Messengers, Horace Silver's original quintet and Thelonious Monk, and when he made dozens of recorded appearances with of these leaders save Monk and under his own name, the tenor saxophonist became relatively scarce. Almost exactly two years separate this album from Peckin' Time, his previous Blue Note effort, and the appearances he made as a sideman in the intervening period can be counted on the fingers of one hand.

Drug problems that would continue to plague Mobley had interrupted his performing career, yet, as the recorded evidence proves, they had not impeded his progress. Beginning here and on the inspired successor dates Roll Call, Workout and Another Workout, in his 1961 recordings with Miles Davis, and on the sessions cut shortly after he left the trumpeter's band in 1963 heard on No Room For Squares and the CD version of Straight, No Filter, Mobley's lovely "round" sound, pinpoint rhythmic execution and sophisticated harmonic concept were at their apex. He was also incorporating some of the new modal and metric currents in jazz without abandoning the vivid personality that had made him a paragon of the hard bop movement.

One reason why Soul Station stands at the head of Mobley's magnificent 1960-63 body of work, and why it has been frequently called his Saxophone Colossus or Giant Steps, is because it finds him in a quartet setting, minus the trumpet and other horns commonly featured on his dates. In this regard it harkens back to his 1955 debut as a leader, the 10-inch Blue Note album Hank Mobley Quartet, which was one of his own favorite recordings. Art Blakey was present there and here, and in the intervening years the drummer had perfected the polyrhythmic commentary, the dramatic press rolls and the galvanic swing that defined his style as surely as Mobley had marshalled his own techniques. Where fellow Jazz Messengers Horace Silver and Doug Watkins completed the rhythm section on the earlier quartet date, Wynton Kelly and Paul Chambers appear here. Each had recorded with Mobley before, and a year later both would be supporting the saxophonist in the Davis band. Each is at the top of his game here, and would prove equally inspired on Mobley's subsequent 1960 and '61 Blue Note sessions.

What these four musicians produced in Rudy Van Gelder's studio on February 7, 1960 is one of the finest programs of music on Blue Note or any other label. On the surface it does not seem like much, just two standards, two bluesy originals and two faster blowing lines; but as usual Mobley had attended to details. "Remember" and "If I Should Lose You" are quality songs that were not overplayed, "Dig Dis" and "Soul Station" served the funky demands of the time with heartfelt eloquence, and "This I Dig Of You" and "Split Feelin's" are memorable melodies with rewarding structures. All six are delivered with a natural ease that may create a misleading impression of easy music — what could sound easier, for instance, than the opening choruses of "Remember?" — yet that is part of the brilliance behind the album. If everybody could toss off music this satisfying, then Soul Station would have far more company at the pinnacle of recorded jazz.

— Bob Blumenthal, 1999

Blue Note Spotlight - August 2019

http://www.bluenote.com/spotlight/next-stop-hank-mobleys-soul-station/

In 1960, when Hank Mobley laid down his classic album Soul Station, the tenor saxophone was the sovereign instrument on the jazz bandstand, rivaled only by the trumpet. Mobley had plenty of company in the tenor zone, with the authority and spirituality of John Coltrane, the colossal and expressive clout of Sonny Rollins, and the auspicious ascendancy of Wayne Shorter as a brilliant composer and future jazz Zen Master apprenticing with one of jazz’s Rock of Gibraltar bands, Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers (in which Mobley had also played).

What Mobley brought to the tenor saxophone was his deep-bodied, melodic soul. With his singular saxophone voice, Mobley slipped from the ’50s hard bop realm into the soul jazz and post-bop sound of of the ’60s. As such, he has been heralded as one of the major forces on tenor in the period of time where he recorded for Blue Note—a total of 25 albums from 1955 (Hank Mobley Quartet with Blakey, pianist Horace Silver, and bassist Doug Watkins) to 1970 (Thinking of Home with trumpeter Woody Shaw, pianist Cedar Walton, guitarist Eddie Diehl, bassist Mickey Bass, and drummer Leroy Williams).

On Soul Station, recorded at Rudy Van Gelder’s Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey studio, Mobley enlisted an all-star rhythm section comprised of Blakey as well as bassist Paul Chambers and pianist Wynton Kelly, both in Miles Davis’s classic ‘50s band. They supply the swing and groove to the six tunes on the album—two standards that open and close the collection with four lyrical Mobley originals in the middle—while the tenor saxophonist flows and glows effortlessly through the lyricism that embodies all the music here.

Mobley starts the session with his sunny rendering of Irving Berlin’s “Remember,” with a tenderly smooth ride that he blows extra gusto into as the tune develops. The bouncy “This I Dig of You,” features Mobley’s stirring round tone and Blakey’s smashing solo break. Kelly establishes the groove on “Dig Dis” that Mobley blows into in his laid-back but tasty style. On the blues-steeped title tune, Mobley luminously holds court for the first half before letting his band stretch.

Taken as a whole, Soul Station exemplifies with its dance-like sensibility the satisfying accessibility of a vital swath of jazz during the early ’60s. Mobley steers clear of stratospheric strides on Soul Station; he’s firmly planted on sweet terra firma.

Blue Note Spotlight - April 2021

https://www.bluenote.com/spotlight/next-stop-hank-mobleys-soul-station/

In 1960, when Hank Mobley laid down his classic album Soul Station, the tenor saxophone was the sovereign instrument on the jazz bandstand, rivaled only by the trumpet. Mobley had plenty of company in the tenor zone, with the authority and spirituality of John Coltrane, the colossal and expressive clout of Sonny Rollins, and the auspicious ascendancy of Wayne Shorter as a brilliant composer and future jazz Zen Master apprenticing with one of jazz’s Rock of Gibraltar bands, Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers (in which Mobley had also played).

What Mobley brought to the tenor saxophone was his deep-bodied, melodic soul. With his singular saxophone voice, Mobley slipped from the ’50s hard bop realm into the soul jazz and post-bop sound of of the ’60s. As such, he has been heralded as one of the major forces on tenor in the period of time where he recorded for Blue Note—a total of 25 albums from 1955 (Hank Mobley Quartet with Blakey, pianist Horace Silver, and bassist Doug Watkins) to 1970 (Thinking of Home with trumpeter Woody Shaw, pianist Cedar Walton, guitarist Eddie Diehl, bassist Mickey Bass, and drummer Leroy Williams).

On Soul Station, recorded at Rudy Van Gelder’s Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey studio, Mobley enlisted an all-star rhythm section comprised of Blakey as well as bassist Paul Chambers and pianist Wynton Kelly, both in Miles Davis’s classic ‘50s band. They supply the swing and groove to the six tunes on the album—two standards that open and close the collection with four lyrical Mobley originals in the middle—while the tenor saxophonist flows and glows effortlessly through the lyricism that embodies all the music here.

Mobley starts the session with his sunny rendering of Irving Berlin’s “Remember,” with a tenderly smooth ride that he blows extra gusto into as the tune develops. The bouncy “This I Dig of You,” features Mobley’s stirring round tone and Blakey’s smashing solo break. Kelly establishes the groove on “Dig Dis” that Mobley blows into in his laid-back but tasty style. On the blues-steeped title tune, Mobley luminously holds court for the first half before letting his band stretch.

Taken as a whole, Soul Station exemplifies the satisfying accessibility of a vital swath of jazz during the early ’60s. Mobley steers clear of stratospheric strides on Soul Station; he’s firmly planted on sweet terra firma.

No comments:

Post a Comment