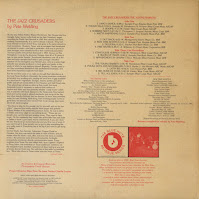

The Jazz Crusaders - The Young Rabbits

Released - 1975

Recording and Session Information

Pacific Jazz Studios, Hollywood, CA, January 7, 1962

Wayne Henderson, trombone; Wilton Felder, tenor sax; Joe Sample, piano; Sticks Hooper, drums; and Jimmy Bond as Jimmy Boyd, bass.

(16547) Big Hunk Of Funk

(16548) Till All Ends

E8841 (16544) The Young Rabbits

"The Lighthouse", Hermosa Beach, CA, August 5 & 6, 1962

Wayne Henderson, trombone; Wilton Felder, tenor sax; Joe Sample, piano; "Sticks" Hooper, drums; and Victor Gaskin, bass.

(16541) Congolese Sermon

(16543) Appointment In Ghana

Pacific Jazz Studios, Hollywood, CA, February 19, 1963

Wayne Henderson, trombone; Wilton Felder, tenor sax; Joe Sample, piano, harpsichord; Stix Hooper, drums; and Bobby Haynes, bass.

(16534) Boopie

Pacific Jazz Studios, Hollywood, CA, July 19, 1964

Wayne Henderson, trombone, euphonium; Wilton Felder, tenor, alto sax; Joe Sample, piano; Stix Hooper, drums; and Joe Pass, guitar #2,3; Monk Montgomery, Fender bass.

(16535) Robbin's Nest

(16537) Out Back

(16545) Polka Dots And Moonbeams

Pacific Jazz Studios, Hollywood, CA, February 22, 1965

Wayne Henderson, trombone; Wilton Felder, tenor sax; Joe Sample, piano; Stix Hooper, drums; and Victor Gaskin, bass.

(16538) New Time Shuffle

Pacific Jazz Studios, Hollywood, CA, July 1, 1965

Wayne Henderson, trombone; Wilton Felder, tenor sax; Joe Sample, piano; Nesbert Hooper, drums; and Hubert Laws Jr., flute; Clare Fischer, organ; Al McKibbon, bass; Carlos Vidal, congas; Hungaria Garcia, timbales, cowbell.

(13167) Tough Talk

(16546) Latin Bit

Pacific Jazz Studios, Hollywood, CA, July 2, 1965

Wayne Henderson, trombone; Wilton Felder, tenor sax; Joe Sample, piano; Nesbert Hooper, drums; and Hubert Laws Jr., flute; Clare Fischer, organ; Al McKibbon, bass; Carlos Vidal, congas; Hungaria Garcia, timbales, cowbell.

(16539) Dulzura

"The Lighthouse", Hermosa Beach, CA, January 14-16, 1966

Wayne Henderson, trombone; Wilton Felder, tenor sax; Joe Sample, piano; Stix Hooper, drums; and Leroy Vinnegar, bass.

(16542) Blues Up Tight

Pacific Jazz Studios, Hollywood, CA, May 15, 1967

Wayne Henderson, trombone; Wilton Felder, tenor sax; Joe Sample, piano; "Stix" Hooper, drums; and Charles "Buster" Williams, bass.

(16536) Watts Happening

Liberty Studios, Hollywood, CA, July 10, 1968

Wayne Henderson, trombone; Wilton Felder, tenor sax; Joe Sample, piano, electric piano; Stix Hooper, drums; and Buster Williams, bass.

(16540) Fire Water

Liberty Studios, Hollywood, CA, July 11, 1968

Wayne Henderson, trombone; Wilton Felder, tenor sax; Joe Sample, piano; Stix Hooper, drums; and Buster Williams, bass.

(16533) Fancy Dance

Track Listing

| Side One | ||

| Title | Author | Recording Date |

| Fancy Dance | J. Sample | July 11 1968 |

| Tough Talk | Hooper-Sample-Henderson | July 1 1965 |

| Boopie | W. Felder | February 19 1963 |

| Robbins Nest | I. Jacquet-Sir C. Thompson | July 19 1964 |

| Watts Happening | J. Sample | May 15 1967 |

| Side Two | ||

| Outback | W. Montgomery | July 19 1964 |

| New Time Shuffle | J. Sample | February 22 1965 |

| Dulzura | C. Fischer | July 2 1965 |

| Fire Water | C. A. Williams, Jr | July 10 1968 |

| Side Three | ||

| Congolese Sermon | W. Henderson | August 5-6 1962 |

| Blues Up Tight | J. Sample | January 14-16 1966 |

| Appointment In Ghana | J. McLean | August 5-6 1962 |

| Side Four | ||

| The Young Rabbits | W. Henderson | January 7 1962 |

| Polka Dots And Moonbeams | J. Van Heusen | July 19 1964 |

| Latin Bit | K. Cox | July 1 1965 |

| Big Hunk Of Funk | W. Felder | January 7 1962 |

| Till All Ends | J. Sample | January 7 1962 |

Liner Notes

THE JAZZ CRUSADERS

By the time Wilton Felder, Wayne Henderson, Stix Hooper and Joe Sample, better known collectively as the Jazz Crusaders, began recording for Pacific Jazz Records in 1961 they already had been working uninterruptedly as a unit for almost a decade. They had been friends for most of their lives, had gone to the same schools in their hometown, Houston, Texas, and as teenagers had developed an interest in music—and jazz in particular—that was to prove an even stronger, more durable bond to their continued association. The four youths formed their first band in 1953. Known as The Swingsters, it was led by drummer Hooper, then all of 15 years of age, as was pianist Sample. Trombonist Henderson was 14 at the time and tenor saxophonist Felder a year younger. (Another member of The Swingsters was Hubert Laws, who as a junior high schooler was already proficient on both guitar and reeds, to the study of which he was applying himself diligently.) Tender years or no, they considered themselves fully professional musicians, and their work experience supports their claim.

For the next five years or so, right on through their attendance at the local Texas Southern University, the young musicians continued to function as a working unit, playing the usual sort of gigs available to a local band —nightclubs, lounges, dances, parties and other public and private social affairs in the Houston and Gulf Coast area. They played jazz, at least as often as they could, but more frequently found it necessary to perform that mixture of rhythm-and-blues and jazz generally labeled "jump music" which was so popular with black listeners in the Texas area; they backed local and touring singers; played standards, pop songs of the day and other heavily rhythmic fare for dancers. In short, they provided music for hard drinking, hard living, hard working people out for a good time, for listeners who wanted their music strong, direct and, above all, hard swinging.

"You have to play for the people, not for yourself, and not for the critics," observed the widely popular blues singer and guitarist T-Bond Walker of the performing scene in Texas. He was a native of Dallas and knew what he was talking about. "These are not people who want to read and analyze music. They want to hear music. On the weekends they crowd into all the little bars and clubs in Dallas to have a good time and be entertained. If you ain't doin' the job, they'll just go somewhere else and you'll be out of work. If you want to get to these people you've got to play everything like you really mean it. Everything has to be big if you want to get along in Dallas."

Or Fort Worth, San Antonio, Galveston, Corpus Christi or Houston: the story was much the same in each of them, and no matter what the music—jazz, r&b, rock and roll, blues or country music — the pressures were all towards powerful, forthright, persuasively emotional, directly communicative music. Every musician from Texas I've ever talked with, from Lightnin' Hopkins to Doug Sahm, has remarked on Texas audiences' insistence on the straightforward, heartfelt expression of deep feeling in any and all music directed their way. Nor will they in fact settle for anything less. "Most folks down in Texas come from the heart of Texas."

While Freedom Sound was without doubt a striking achievement for, and effective introduction to a new group, the set that followed it, Lookin' Ahead (Pacific Jazz 43), recorded only eight months later, was even more impressive an effort both in what it attempted and what it achieved. In these performances — three of which are included here, The Young Rabbits, Big Hunk of Funk and Till All Ends — all of the group's diverse sources had been fully integrated into a strong, flowingly cohesive, powerful musical approach of uncommon vigor and assurance. There is nothing tentative or unformed about any of them, in fact. The performances all but crackle with electricity and the very best of them literally stun you with their untrammeled force and ravishing fervor.

One of the album's selections, The Young Rabbits, was issued — in edited form — as a single and assumed near-hit proportions for the group. It's easy to see why. From its very first explosive note, the performance all but overwhelms with the blistering, unrelenting ferocity of its attack. (Apparently the lagomorphs in question are unaware of the fabled timidity of their species; accosted by these particular rabbits — "Your lettuce or your life!" — I have no doubt I would immediately surrender any foliage I had on or about my person.) The title possibly alludes to the then popular television cartoon figure, Crusader Rabbit, but whatever the inspiration (Wayne Henderson's original title for it was Little Erma and Big Kemp, by the way), the performance itself is a bitch. The composer is up first, his trombone burning with an almost ominous sound, and Felder continues strongly with a tenor solo of liquid fire, leading into Hooper's volcanic eruptions before Jimmy Bond's bass signals a return to the theme and out. All one can say is "Whew!" A phenomenal performance, even by Jazz Crusaders' standards.

Big Hunk of Funk is aptly named, Felder's attractive composition perfectly embodying the engagingly unpretentious qualities for which the group has become justly celebrated and supporting compelling solos by the composer, a blowsy Henderson, effervescent Sample, as well as a brief taste of Bond. I would have thought Henderson the author of Till All Ends, for its evocation of the characteristic Jay and Kai sound is the sort of thing a trombonist might be expected to write but, no, this brisk excursion was composed by Joe Sample and is notable for a particularly preaching Henderson improvisation and some lovely, liquid tenor sinuosities from Felder.

Highlighting the album's "live" side are two performances. Congolese Sermon and Appointment in Ghana. recorded at the Lighthouse in Hermosa Beach, Calif., in August of 1962. The redoubtable Victor Gaskin was filling the bass chair as have few men then or since, and his extraordinarily propulsive, big-toned and unerring work animates both of these tracks, among the most effective performances the Jazz Crusaders ever recorded. Always at their best when playing to a responsive audience, the group outdoes itself here. Henderson's Congolese Sermon is taken at a tempo that can only be described as killing but which, more impressive still, never flags once over almost seven minutes of spiraling intensity, the high point of which is Sample's breathtaking, unrelentingly inventive improvisation, to which Henderson's and Felder's forceful work, gripping though they are, must inevitably take a back seat. Jackie McLean's attractive Appointment in Ghana boasts some of Henderson's guttiest work and a bristling cry-filled tenor solo so penetratingly intense that it more than occasionally suggests Felder is actually playing alto saxophone. Rounding out this set of location recordings is a performance of Sample's Blues Up Tight from the group's second Lighthouse set, dating from January, 1966, with the well known Leroy Vinnegar in on bass, and offering balanced, compelling work from all, as well as indicating how greatly they had grown individually and collectively.

An attractive though undeservedly little known classic of the Jazz Crusaders' canon, Boopie was recorded in Feburary of 1963, with bassist Bobby Haynes rounding out the rhythm section. Composer Felder, first up in the solo order, turns in a strong and passionate reading but is given a real run for his money by pianist Sample, who responds to the modal character of the piece with one of his most persuasive and invigorating solos, a flawlessly brilliant jewel of construction and execution, one in fact that his models, Phineas Newborn and Oscar Peterson, might well envy. The piece is further distinguished by one of Hooper's well turned exercises in tuneful percussion. Bassist Monk Montgomery, of the musical Montgomery brothers of Indianapolis and charter member of the Mastersounds, joined the Jazz Crusaders for a national tour shortly before recording with them in the summer of 1964, from which sessions are here offered three marvelous performances. The appealing Out Back, written by Monk's brother, guitarist Wes Montgomery, is further leavened through the addition of guitarist Joe Pass, the Synanon graduate who was then beginning to make a name for himself as one of the finest Jazz plectrists to have emerged since Tal Farlow and a thoroughgoing, always interesting master of the hardy disciplines of bop. Pass is likewise prominently featured on the moody ballad standard, Polka Dots and Moonbeams, which contains a welcome sample of Felder's fluent work on alto saxophone in addition to Henderson's newly acquired euphonium, a brass instrument he describes as combining the features of trombone, tuba and French horn. "It's actually a more flexible instrument than any of those three," he explained, "but it's an extremely difficult instrument to learn," If so, his flexibly knowing handling of it on this and on Robbins Nest — the jazz standard so closely identified with Illinois Jacquet and primarily a feature for Felder's throaty, full-bodied tenor saxophone — belies any notion of his having experienced difficulty with the instrument, which to these ears seems as fluently incisive as his work on the, to him, more familiar trombone.

Certainly the impression of that particular coast's brand of easily accessible musicmaking has been strongly evident in the group's own approach to playing, to communicating with its listeners, When in 1958 they left Texas to pursue a broader outlet for their music the group, still intact but then known as the Modern Jazz Sextet, had so thoroughly absorbed the gospel of direct, immediate communication with one's listeners they had heard being preached by every musician and group plying their trade in the Gulf Coast area that they had learned to preach that way themselves. It had become so naturally and integrally a part of their music as to be second nature, And if, as their newly assumed name suggested, they felt that their primary allegiance was to Jazz they also felt it was never to be achieved at the expense of genuine, heartfelt emotion or of the enlivening pulsation of rhythm and blues and other fundamental dance musics. That much at least they had learned.

When they left Houston they carried with them all the musical values and experiences that, a few years later when they had found their proper identity as the Jazz Crusaders, were fully and finally distilled into the strong appealing blend of jazz and funk with which they established their enduring reputation (the very best of which music is to be heard within these covers). What brought them to Los Angeles initially was the hope of a "possible record date" which had been extended them by a man Hooper identified only as "a promoter and clubowner." But, the drummer noted, "The record date never came off," adding with a shrug, "and I haven't even met this individual to this day, though he's quite a bigwig."

The Modern Jazz Sextet had some difficulty in making inroads on the Los Angeles jazz scene, then as now fiendishly tough to crack, with a limited number of major Jazz venues (and those few scattered over a staggeringly huge area) and fierce competition for what jobs are available, the bulk inevitably falling to the well established nationally known "acts" that, in theory at least, are proven audience-drawing attractions. The group played several evenings of Howard Lucraft's Jazz International concert series then being presented weekly at a Hollywood club, and were received enthusiastically. But sufficient work opportunities just were not available to a new, unknown jazz group — one moreover without benefit of a recording contract, promotional and other support from a record company, radio and press exposure, and all the other appurtenances of successful music business merchandising activities —so the Modern Jazz Sextet was forced to look to other avenues.

One such was rock and roll. Hooper takes up the story: "At that time the initials on our music stands read N.H - my name. So the group became the Nite Hawks [or Night Hawkes]. We built an act, a rock and roll act with a singer, Micki Lynn, and we did well in Hollywood," A hard-headed realist, Hooper looked to extend the group's popular success. If they weren't working in jazz, their first love, at least they were working. And succeeding too. "I came on the name Maurice Duke, an agent," the drummer continued, "and persuaded him to hear us. He liked the act and got us to the New Frontier in Las Vegas for 4 1/2' months in the lounge. At the time we featured a Hammond organ in the band."

In time, however, this proved stultifying, Hooper observed. "We got drug with the rock and roll and the jazz fever came back." Having saved some money, the group moved back to Los Angeles and resumed the crusade. On their return, Hooper said, "Immediately we called Dick Bock." President and founder of Pacific Jazz Records, Bock was aware of the group through their appearances at the Jazz International concerts and, moreover, had repeatedly been urged to record them by fellow Texan, saxophonist Curtis Amy, who was then recording successfully for the Los Angeles label, "Bock dug the group," Hooper noted, "but he didn't dig the organ — which we were gassed by," Nor, one suspects, did he especially dig the overt r&b approach of the Nite Hawks edition of the band. In any event, a compromise of sorts was achieved, Bock recorded and issued a single — Bunny Ride and Sweetie Lester (Pacific Jazz 352) — by the Night Hawks and at much the same time recorded the first album issued by the group's most widely known incarnation, the Jazz Crusaders. The album was Freedom Sound, recorded in May of 1961 and issued the critical reaction was, to put it mildly, highly enthusiastic. It's instructive to quote Down Beat reviewer Frank Kofsky's long, laudatory review of the group's maiden recording effort:

After describing the Jazz Crusaders as "one of the outstanding new groups made up of younger musicians," Kofsky went on to remark, "Barely out of their teens, they nonetheless play, for the most part, with the assurance of more mature men. Moreover, they can write; all of the tunes save the Exodus theme came from within the band...This, coupled with their long-time association, allowed them to build a repertoire and group sound that grabs and holds your attention. Even the obligatory gesture in the direction of fundamentalism, The Geek, is above average in interest."

Kofsky continued with assessments of the individual members: "It takes only half a dozen notes to tell that Felder is a Texan, so heavily is he in that David Newman-Curtis Amy groove. There is an almost hysterical edge in his tone that, were it a bit more pronounced, might be annoying. As it is, it just lifts you right out of your chair. He is the group's major solo voice.

"Henderson's trombone is generally in the J.J, Johnson tradition but with just the right hint of raucousness to provide Felder with the proper complement.

"Though he has been listening to Wynton Kelly (and what young pianist has not?), among others, Sample seems well on the way to achieving an identity.

"Hooper is a tasty drummer, and together with Bond [Los Angeles bassist Jimmy Bond, who was added to the band for the album, replacing the group's regular bassist, described by Hooper as "lost permanently to rock and roll"], he provides a solid rhythmic base."

Kofsky's reaction was typical of the group's reception in the jazz press. Richard Hadlock, a critic not overgiven to enthusiastic excess, described their sound as, "The full cry of youth with the wisdom of long working experience," and went on to note, "This is what jazzmen call a 'hard' band, in which each musician gives his all to every performance. The result is a rushing, vociferous spiral of sound that forever threatens to soar beyond the limits of control, but somehow never does. Tempering this ferocity of musical outlook is a deep vein of affability that seems to characterize the Crusaders' collective and individual playing styles."

(To get an idea of just what enthused them so greatly, consult the several performances from that album — M,J,S. Funk, That's It and Freedom Sound—that have been included in the recent Tough Talk two-LP set (Blue Note BN-LA-170-G2), which offers a hefty sampling of the Jazz Crusaders' punchiest, most infectiously accessible music and which, in its more popular orientation, nicely complements this album's much stronger jazz bias.)

The following February, Montgomery still on board, the group put down Sample's New Time Shuffle, an intriguing material exercise that counterpoised a tart modern melody line against an old fashioned boogie-ish bottom, the jaxtaposition of the two giving the piece an oddly appealing, wry exuberance that was as nicely effective as it was unusual.

Another of the Jazz Crusaders' occasional recorded meetings with guest artists took place July of 1965 when flutist Hubert Laws was reunited with fellow Swingsters and Modern Jazz Sextet members for a memorable series of performances, all of which had a pronounced Latin cast to them, thanks to the further participation of Latin percussionists Carlos Vidal and Hungaria Garcia, organist Clare Fischer and veteran bassist Al McKibbon. Indicative of the high-spirited, celebratory nature of the proceedings are the three selections included here — the infectiously funky Tough Talk, a collective effort by Sample, Henderson and Hooper, which boasts a stunning Felder solo; Fischer's supple, persuasively idiomatic samba, Dulzura, with successive solos by Laws, Felder and Sample; and Kenny Cox's simple but attractive Latin Bit, with all hands showing — from one of the sunniest, most warmly appealing and successful of all the group's many recordings.

The final three selections in point of time, with the gifted young bassist Buster Williams present, were recorded in May of 1967 Water). Henderson described Sample's Watts Happening as "'a beautiful power-packed melody, and it really has that sound. It opens with a very hip rhythmical pattern laid down by the rhythm section, which provides a strong vehicle for getting into the tune." Still, he feels he wasn't "really ready for this tune when we recorded it, and I know, because I struggled from beginning to end," which explains the relative brevity of his solo, "Wilton spit out some things that really began to give the song a lift...Joe said that he was dissatisfied with the changes, or that his right hand was stiff, or something, but after listening to how well he played, I was trying to figure out what he was talking about, 'Stix' and 'Buster' kept cattin' through the whole tune, and they really held it together."

Sample also composed the laid-back Fancy Dance, one of those deceptively easy sounding pieces with an almost ageless quality to it and, as such, perfectly typifying the Jazz Crusaders' music at its bluesy, ebullient best and most accessible. Similar in orientation is Buster Williams' Fire Water, as fine an example of sturdy post-bop modernism as one might find anywhere, with more than an occasional reference to so-called free music, and enabling the soloist to go in either or both of these directions, as in fact happens here, most notably in Felder's solo segment.

Since these recordings were made the group has chosen to pursue a somewhat different course. A few years ago Hooper, Felder, Henderson and Sample, in a pronouncement given wide circulation in the music press, elected to drop the designation 'jazz" from the group's name no less than from its music, which since then has hewed to a more overtly commercial direction than is represented by the strong, undiluted Jazz performances that make up this album. It must be admitted, too, that the Crusaders, as the four are known these days, have achieved a much wider and more conspicuous popular acceptance than ever they enjoyed in their years as the Jazz Crusaders.

Still, however much one might sympathize with, or defend the quartet's right to follow whatever artistic and/or commercial goals they desire, inevitably one wishes they could have satisfied those goals as the Jazz Crusaders, that they could have continued to pursue longer and more deeply the directions charted in these and like performances. That, in other words, it had not been necessary for them to become the Crusaders. In this connection writer Leroy Robinson, in urging black listeners to more actively support jazz as the unique artistic contribution to American and world culture it so manifestly is, observed recently, "There is a definite and urgent need for blacks to return to jazz music just as we need the Crusaders to return to the fold as the 'Jazz Crusaders: Their departure could, in part. be blamed on the lack of black support, not of the Jazz Crusaders but of Jazz in general?

One inevitably suspects the reasons for their taking up a more broadly popular stance in their music are deeper and more complex than lack of support from the black jazz listener. The problem is much more severe and far more widespread than just that, One thing, however, is clear and undisputed: Now more than ever we have need of the buoyant spirit and joyous, affirmative, uncomplicated communication we once were privileged to receive from the Jazz Crusaders. They are missed, and sorely at that. If proof is needed, listen to the enclosed.

PETE WELDING

No comments:

Post a Comment