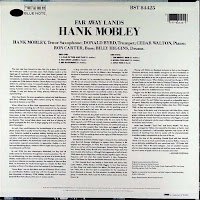

Hank Mobley - Far Away Lands

Released - 1985

Recording and Session Information

Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, May 26, 1967

Donald Byrd, trumpet; Hank Mobley, tenor sax; Cedar Walton, piano; Ron Carter, bass; Billy Higgins, drums.

1898 tk.3 No Argument

1899 tk.6 The Hippity Hop

1900 tk.9 Bossa For Baby

1901 tk.12 Soul Time (aka Dusty Foot)

1902 tk.27 Far Away Lands

1903 tk.32 A Dab Of This And That

Track Listing

| Side One | ||

| Title | Author | Recording Date |

| A Dab of This and That | Hank Mobley | May 26 1967 |

| Far Away Lands | Jimmy Heath | May 26 1967 |

| No Argument | Hank Mobley | May 26 1967 |

| Side Two | ||

| The Hippity Hop | Hank Mobley | May 26 1967 |

| Bossa for Baby | Hank Mobley | May 26 1967 |

| Soul Time | Donald Byrd | May 26 1967 |

Liner Notes

The train ride from Newark to New York City is about 25 minutes, but in the jazz world, it can take years. Hank Mobley made it at the legal age of manhood, 21 years old, when Max Roach guested with Paul Gayten's Newark band, which featured Hank. Roach hired him immediately. As Mobley told John Litweiller in Down Beat, "We opened in a place on 125th Street in Harlem. Charlie Parker had just been there before me, and here I come. I'm scared to death — here's Sonny Rollins, Jackie McLean, Kenny Dorham, Gerry Mulligan, just about all the young musicians came by there....At the time it was like going to college. It was just doing our thing, playing different changes, experimenting."

After Max Roach, the tenor saxophonist worked with Tadd Dameron and Dizzy Gillespie among others before joining the Horace Silver Quartet at Minton's in mid 1954.

When Alfred Lion of Blue Note approached Horace Silver about doing some more recording, but with horns instead of trio, he selected Mobley and bassist Doug Watkins from his quartet and Art Blakey and Kenny Dorham, with whom he had worked frequently around the city in those years. In late '54 and early '55, they cut three 10" lps, two as the Horace Silver Quintet and one without Dorham as the Hank Mobley Quartet. Their mutual ideas about music and love of playing together prompted the five men to begin gigging and recording as The Jazz Messengers.

As such, they would become the fountainheads of an earthy new phase of jazz that is usually termed hard bop. The jazz public and the critics' fraternity tended to overlook Mobley, thinking him an unlikely candidate to carry that particular jazz message. For one thing, he had a soft tone, which was out of fashion in a world dominated by the tones of Coltrane and Rollins. His rhythmically subtle and intricate patterns of improvisation required concentration to appreciate. Mobley is a brilliant and absorbing player; whatever effort it might take to get to that is rewarding and worthwhile.

By mid 1956, the Jazz Messengers disbanded, but they had all made names for themselves through their mutual association. The 12" lp was blossoming, thus jazz recording was at one of its busiest levels. Mobley made dates of his own for Savoy and Prestige and made the rounds as a sideman on countless sessions, the majority of them on Blue Note. In November, he would record again as a leader for Blue Note and play on Silver's first album since the breakup of the Messengers.

"Senor Blues" was on that album and set off Horace Silver's career as a bandleader. Mobley would stay with him through '57. And from that November to February, 1958, Mobley would record an unprecendented 8 Blue Note albums of his own in sixteen months.

A drug conviction took him off the scene for about a year, after which he played and wrote for Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers. He left the band in September and finally began recording on his own again in 1960. During '60 and '61, he recorded Soul Station, Roll Call, Workout, and the as yet unissued Another Workout, all with Wynton Kelly and Paul Chambers present. Mobley's tone became more intriguing and full voiced. His style reached an extraordinary level of lyricism, distillation and structural sense. These sessions might well be considered his masterpieces. His new approach was perfectly suited to the Miles Davis Quintet, of which he was a member throughout 1961 and 1962.

In 1963, Mobley again resumed recording for Blue Note. And this third phase, introduced by No Room For Squares featured a more aggressive and economic Mobley in both sound and choice of notes. It was as if his playing evolved to suit the ensemble sound that he had helped to create. But it was still Mobley, with his sparkling sense of inner logic and inventive left turns. He was merely presenting it in a more direct and forceful manner.

Conflicts between his drug habit and the law took him off the scene again in 1964. He emerged in 1965, clean and revitalized and picked up where he had left off. He recorded under his own name for Blue Note regularly until 1970 and worked whenever possible with his own group or in tandem with Lee Morgan. Of course, he continued to pop up frequently on other people's Blue Note dates and gigged off and on with Elvin Jones and Kenny Dorham. At the time of recording Far Away Lands, the saxophonist had just returned from two months of touring in Europe. In 1968, he would go back at the urging of Slide Hampton and remain there for two years.

Donald Byrd and Hank Mobley began a long and close relationship when Byrd left George Wallington to replace Kenny Dorham in the original Jazz Messengers. In 1956, they would record on each other's albums as well as with the Jazz Messengers, Horace Silver, Doug Watkins, Jimmy Smith, Kenny Burrell and a beautiful Elmo Hope date that also included John Coltrane. Although Hank appeared on half of Byrd's 1960 album Byrd In Flight, they would not play together again with any frequency until '63 when they made Donald's A New Perspective, Hank's No Room For Squares and Herbie Hancock's My Point Of View.

In 1967, Donald Byrd was leading a fixed band with Sonny Red, Cedar Walton, Walter Booker and Billy Higgins. In fact, they had just cut Slow Drag two weeks before this album. The band grew out of a late 1966 stint at the Five Spot in preparation for the recording of Byrd's Blackjack in January. For that occasion, he added Mobley to the group. A month later, Hank used the rhythm section intact on his Third Season lp.

Playing with Walton on Blackjack and prior to that on Lee Morgan's Charisma obviously struck Mobley enough to use him immediately on his next two record dates. Cedar's strength, technique, harmonic sophistication and ability to lay into a groove and build on it were exactly suited to Mobley's music. When Mobley returned from Europe in 1970, he used Cedar on his last Blue Note lp Thinking Of Home. Before long, they assembled a quintet in which they shared leadership. That band lasted into '72 and worked with some consistency on the East Coast, making one album for Cobblestone (now Muse).

Higgins was the Blue Note house drummer, and his playing can tell you why. His sense of swing is incredible and unyielding, yet he is able to contribute a complex array of accents and polyrhythms that interact with each soloist. He and Walton have proved an unbeatable team in this genre. Today they are still playing together and making magnificent music. Higgins was on every Hank Mobley date from 1965 through 1968. As they say, accept no substitutes.

Ron Carter, at this point, was in his last year with Miles Davis, whose music would soon move in a more electric direction. Ron's ability to project resilience and solid strength at the same time is that rare quality that separates the master from the journeyman. Like Higgins, he could feed all sorts of elements into the music without ever loosening his grip on the bass' basic function.

Aside from Donald's "Soul Time" and Jimmy Heath's "Far Away Lands" arranged by Walton, the material for this album is Hank's. And typically, he conceived a well-rounded repertoire that covers all the avenues of hard bop from funk to samba with his characteristically irresistible modern compositions as the core of the set.

Near the time of this recording, Donald Byrd told Nat Hentoff, "Hank is to me just as much a personality as Sonny Rollins. I mean, he has so definitely established his own sound and style." Of Cedar Walton, he said, "He's in the same category...he's an excellent musician who has been playing a supporting role and has never really come into his own in terms of public renown as a musician and writer."

—MICHAEL CUSCUNA

No comments:

Post a Comment