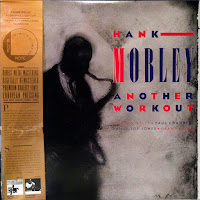

Hank Mobley - Another Workout

Released - 1985

Recording and Session Information

Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, March 26, 1961

Hank Mobley, tenor sax; Wynton Kelly, piano; Paul Chambers, bass; Philly Joe Jones, drums.

tk.21 Three Coins In A Fountain

Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, December 5, 1961

Hank Mobley, tenor sax; Wynton Kelly, piano; Paul Chambers, bass; Philly Joe Jones, drums.

tk.2 Gettin' And Jettin'

tk.8 Out Of Joe's Bag

tk.9 Hank's Other Soul

tk.15 I Should Care

tk.16 Hello, Young Lovers

Session Photos

Photos: Francis Wolff

Track Listing

| Side One | ||

| Title | Author | Recording Date |

| Out of Joe's Bag | Hank Mobley | December 5 1961 |

| I Should Care" | Cahn, Stordahl, Weston | December 5 1961 |

| Gettin' and Jettin' | Hank Mobley | December 5 1961 |

| Side Two | ||

| Hank's Other Soul | Hank Mobley | December 5 1961 |

| Hello Young Lovers | Hammerstein, Rodgers | December 5 1961 |

| Three Coins in a Fountain | Styne, Cahn | March 26 1961 |

Liner Notes

Those within the jazz community have been boasting about Hank Mobley's subtle brilliance for some thirty years. His lengthy tenures with Horace Silver, Max Roach, Art Blakey, and Miles Davis, and brief stints with Todd Dameron, Thelonious Monk, and Dizzy Gillespie, among others, are ample proof of his standing among his peers. Yet his entire career has been plagued by a lack of public support, compounded periodically by financial, personal, and health problems.

Mobley, who became 55 on July 7, 1985, lives in Philadelphia and performs there infrequently. Because of serious lung problems, his playing is only sporadically representative of his real genius. The jazz life has brought him little more than an increasingly difficult obstacle course. He has been called underrated for so long that it seems to have become an irreversible fact rather than a problem that needs rectifying.

Most speculation about his lack of acceptance centers around the fact that the post-bop tenor sound was typically hard-edged and robust. Hank's tone was always much rounder and smoother. But beyond tone, Mobley's work demands careful listening. Each solo is an intricate entity, a whole that is greater than the sum of its parts. His ideas and phrasing are as subtle as his tone. Most likely, his greatness merely eluded the average listener.

Hank's Blue Note association as a leader falls into three periods. The first began in 1954 when his playing was just coming into its own. Mobley, Kenny Dorham, Horace Silver, Doug Watkins, and Art Blakey formed the Jazz Messengers and became the nucleus for a number of fine albums on Blue Note under the rotating leadership of all but Watkins. This was a fertile and active time for Hank. He made eight Blue Note sessions under his own leadership between November 1956 and February 1958.

Although he continued to remain quite active as a player and composer, he did not make another album of his own for two years. Then, in 1960 and '61 , he recorded four albums for the label that capture him at his most brilliant period, fully charged without losing any of his grace or subtlety. The first was Soul Station, a masterful tour de force with Wynton Kelly, Paul Chambers, and Art Blakey. With the same rhythm section and Freddie Hubbard added, he made Roll Call. In 1961 , with Philly Joe Jones in place Of Blakey, he cut Workout with Grant Green making it a quintet. Finally comes this quartet session with that band, released now for the first time as Another Workout. These comprise four parts of a complete musical statement by Mobley at a unique pinnacle in his artistic evolution.

The two mainstays throughout these dates are Kelly and Chambers, who by 1961 were Mobley's bandmates in the Miles Davis quintet. The close musical bond among these men predates that band and these albums. But it is aurally evident that it reached its most intimate and meaningful point here.

After the album in hand, Mobley was totally absent from the recording scene for just more than a year. Soon after his return, he made No Room for Squares. But his sound was harder and his playing had changed. As John Litweiller wrote, "Mobley credits the influence of Davis and Coltrane with the '60s simplification of his style, for he consciously abandoned some degree of high detail in favor of concentrating his rhythmic energies." From 1963 to 1970, the tenor saxophonist recorded an impressive string of quintet and sextet albums for Blue Note with this new approach. Most albums had an obligatory funky riff tune, which, coupled with his new sound, increased his success as a recording artist without really compromising his superb artistry.

But, at least for this listener, it is the middle period that gave us the greatest Mobley. And the fact that this material at hand was allowed to sit on a shelf for 24 years seems incomprehensible to me.

The first tune, Mobley's "Out of Joe's Bag," is a case in point. Hank is off and running from the outset, building off of the composition and creating a seamless, self-regenerating stream of ideas. Ingeniously and spontaneously, he crafts his solo into a complex, single statement. Like those long, labyrinth sentences of James Joyce's, missing the slightest phrase can detract from grasping the whole thought.

This piece, with its obvious title reference to Philly Joe Jones, is a clever, boppish, tune with a 16-bar A section and a bridge that is more traditionally 8 bars in length. Kelly rides off of Hank's solo with a single chorus that is brighter, hotter, and richer than most of his solo work. Philly Joe's drum chorus follows the dynamics and structure of the composition beautifully.

The saxophonist's reading of "I Should Care" illustrates the breadth of his dynamic range. Kelly's two choruses have a development and unity that is Mobleyesque. The session's other standard is the unlikely "Hello Young Lovers," which gets an extended treatment in a casual, but swift tempo. "Gettin' and Jettin'" is a Miles-ish kind Of A—A—B—A tune. Mobley's imagination is in high gear through 8 beautiful choruses. Listen to iust his first and last choruses, one right after the other; this is a perfect example of his extraordinary continuity of thought. In the bridge of his second and third choruses, he playfully hints at the grandstanding style of gut-bucket tenor and then fully lets go with his own interpretation of the genre by the fourth chorus. Kelly and Chambers solo before Mobley and Philly Joe trade eights and take it out.

Mobley's third original, "Hank's Other Soul," has that early Jazz Messengers feel to it. Hank's solo is firm and confident. This piece has that solid groove that Blue Note's Alfred Lion always looked for. Philly Joe effectively pushes Kelly during the piano solo with that kind of backbeat shuffle that Blakey made famous in this context. And Chambers turns in an astonishing solo.

Like the late Tina Brooks and Warne Marsh, Mobley is one of those rare, subtle improvisers with the ability to spew forth an unending stream of ideas that draw the listener into his own inner logic.

Hank Mobley will always have much to say. His comeback on a grand scale is awaited by many with great anticipation. Hopefully, it will come. In the meantime, we have some 16 years of wonderful Blue Note recordings to listen to. This album is one of the best.

— Michael Cuscuna

RVG CD Reissue Liner Notes

A NEW LOOK AT ANOTHER WORKOUT

Since this album is one of the classic "unissued" Blue Notes, it herein receives what in effect is a second retrospective set of liner notes. As Michael Cuscuna describes in the essay that accompanied the music's original release in 1985, the music waited over 23 years before surfacing. It finally saw the light of day when Capitol Records (now Capitol/EMI) resurrected the temporarily moribund Blue Note logo and catalog. Hank Mobley was still alive, and the ovation he received for merely taking a bow at the label's relaunch concert at Town Hall was proof enough of the growing fondness with which Mobley's work was then viewed by the jazz community. Listening to the music today, 20 years after Mobley's passing on May 30, 1986, the idea that playing of such quality by such legendary musicians was originally left to languish seems even more astonishing.

Yet there were reasons, general and particular, that offer possible explanations for the curious history of Another Workout — reasons that Cuscuna might have articulated in his original notes had both Mobley and producer Alfred Lion not still been among us. For one thing, and notwithstanding his lengthy and distinguished service with the label, Mobley was not among Blue Note's true stars. Consistent sellers such as Horace Silver, Lou Donaldson, and Jimmy Smith, and newer personalities, including Stanley Turrentine and Grant Green, received more of the label's attention and enjoyed a more frequent release schedule by the early-1960s. Strong as Mobley's music was at the time — and as Cuscuna writes, this was his strongest period — the market had difficulty accommodating even one LP per year by the saxophonist.

That Lion might record Mobley sessions in excess of the public's demand was one way that the producer and his partner Francis Wolff could help their preferred artists address the "financial, personal, and health problems" to which Cuscuna alludes. A few years earlier, at the start of Mobley's career and the dawn of the LP era, the lack of albums in the marketplace encouraged labels to release such excess sessions sooner rather than later, though even the late-'50s found Mobley creating entire albums that waited decades for release. By 1961, business considerations might very well have argued for sitting on the material.

Then circumstances intervened. Mobley went unheard on record for more than 13 months after the December 1961 session that comprises the bulk of Another Workout, suggesting that he was out of circulation for legal or other reasons that would have made him less of a priority to Blue Note. In addition, when he did return to Rudy Van Gelder's studios in 1963, he revisited two of the three originals heard here, although both tunes had been significantly modified and given new titles. "Gettin' and Jettin'," refitted with a haunting introductory vamp, a slower tempo, and a new bridge, was now "Up a Step" (first issued on Mobley's No Room for Squares), while "Hank's Other Soul" got faster, employed Latin 6/8 patterns in place of cut time on the main theme phrases, and also earned a new bridge as "East of the Village" (which was issued on the saxophonist's The Turnaround). The new performances found Jones held over on drums, with the band completed by trumpeter Donald Byrd, bassist Butch Warren, and (two months prior to his own affiliation with Miles Davis) pianist Herbie Hancock.

As good as Mobley sounds here on "Gettin' and Jettin"' and "Hank's Other Soul," he is even better on "Up a Step" and "East of the Village," with the music further enhanced by a similarly charged Jones and a Hancock who cuts Wynton Kelly's less-effervescent-than-usual contributions to the present date. Once the subsequent performances of nearly identical material appeared, it is less surprising that the music here was confined to the vaults, at least until renewed interest in Mobley coupled with the end of his active recording career prompted its release.

You will note that the five tracks cut in December 1961 provided enough music for a full LP. "Three Coins in a Fountain," a track recorded at the March '61 session that produced Mobley's Workout, had been omitted from that album due to space limitations. Because it did not include Grant Green, who is heard on the remainder of Workout, it fit programmatically with the rest of the present material; and because the added length of the compact disc was still in the future (however near) in 1985, it was included here as the best way to get more prime Mobley into circulation. CD technology has allowed "Three Coins" to be reunited with the rest of the March material on recent reissues of Workout and, therefore, it is not duplicated here.

— Bob Blumenthal, 2006

No comments:

Post a Comment