Hank Mobley - Poppin'

Released - 1980

Recording and Session Information

Van Gelder Studio, Hackensack, NJ, October 20, 1957

Art Farmer, trumpet; Hank Mobley, tenor sax; Pepper Adams, baritone sax; Sonny Clark, piano; Paul Chambers, bass; Philly Joe Jones, drums.

tk.3 Gettin' Into Something

tk.6 Poppin'

tk.8 East Of Brooklyn (aka Night Watch)

tk.9 Tune Up

tk.12 Darn That Dream

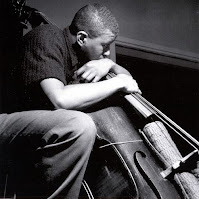

Session Photos

|

| rehearsal |

Photos: Francis Wolff

Track Listing

| Side One | ||

| Title | Author | Recording Date |

| Poppin' | Hank Mobley | October 20 1957 |

| Darn That Dream | DeLange-Van Heusen) | October 20 1957 |

| Gettin' into Something | Hank Mobley | October 20 1957 |

| Side Two | ||

| Tune-Up | Miles Davis | October 20 1957 |

| East of Brooklyn | Miles Davis | October 20 1957 |

Liner Notes

In the mid-1950s the Blue Note label yielded momentarily to supersalesmanship, releasing such albums as "The Amazing Bud Powell," "The Magnificent Thad Jones," and "The Incredible Jimmy Smith." That trend was dormant by the time Hank Mobley became a Blue Note regular and unfortunately so — a record entitled "The Enigmatic Hank Mobley" would have been a natural.

"To speak darkly, hence in riddles" is the root meaning of the Greek word from which "enigma" derives; and no player, with the possible exception of Elmo Hope, has created a more melancholically quizzical musical universe than Mobley, one in which "tab A" is calmly inserted in "slot D."

Mobley is a musician who bears little resemblance to any other. Though he was influenced by Sonny Stitt and, perhaps, Lucky Thompson, he has proceeded down his own path with a rare singlemindedness, relatively untouched by the stylistic upheavals that marked the work of his major contemporaries, Sonny Rollins and John Coltrane.

In the words of Friederich Nietzsche, not previously known for his interest in jazz, Mobley's music is "without grimaces, without counterfeit, without the lie of the great style. It treats the listener as intelligent, as if he himself were a musician. I actually bury my ears under this music to hear its causes."

And that is the enigma of Mobley's art: In order to hear its causes, the listener must bury his ears under it. In a typical Mobley solo there is no drama external to the developing line and very little sense of "profile" the quality that enables one to "read" a musical discourse as it unfolds. Not that high-profile players — Rollins and Dexter Gordon, for example — are unsubtle, But to understand Mobley the listener does have to come to terms with complexities that seem designed to resist resolution.

First there is his tone. Always a bit lighter than that of most tenormen who worked in hard bop contexts, it was, when this album was made, a sound of feline obliqueness — as soft, at times, as Stan Getz' but blue-grey, like a perpetually impending rain cloud.

Or to put it another way, Mobley, in his choice of timbres, resembles a visual artist who makes use of chalk or watercolor to create designs that cry out for an etching tool.

Harmonically and rhythmically, he could also seem at odds with himself. For proof that Mobley has a superb ear, one need listen only to his solo here on Miles Davis' "Tune Up." The apparently simple but tricky changes pretty much defeat Art Farmer and Pepper Adams; but Mobley glides through them easily, creating a line that breathes when he wants it to, not when the harmonic pattern says "stop."

And yet no matter how novel his harmonic choices were — at this time he surely was as adventurous as Coltrane — Mobley's music lacks the experimental fervor that would lead Coltrane into modality and beyond. Mobley's decisions were always ad hoc; and from solo to solo, or even within a chorus, he could shift from the daring to the sober. What will serve at the moment is the hallmark of his style; and thu% though he is always himself, he has in the normal sense hardly any style at all.

Even more paradoxical is Mobley's sense of rhythm. His melodies float across bar lines with a freedom that recalls Lester Young and, Charlie Parker; and he accents on weak beats so often (creating the effect known in verse as the "feminine ending") that his solos seem at first to have been devised so as to baffle even their maker. But that, I think, is not the case.

Equipped with all the skills of a great improviser, Mobley simply refuses to perform the final act of integration; he will not sum up his harmonic, rhythmic, and timbral virtues and allow any one element to dominate for long, In that sense he is literally a pioneer, a man whose innate restlessness never permits him to plant a flag and say "here I stand."

Thus, to speak of a mature or immature Hank Mobley would be inappropriate. Once certain technical problems were worked out — say, by 1955 — he was capable of producing striking music on any given day. New depths were discovered in the 1960s and the triumphs came more frequently; but in late 1957, when "'Poppin' was recorded, he was as likely as ever to be "on."

Much depended on his surroundings, and the band he works with here has some special virtues. The rhythm section is one of the great hard-bop trios, possessing secrets of swing that now seem beyond recall. Philly Joe Jones and Paul Chambers, partners, of course. in the Miles Davis Quintet, shared a unique conception of where "one" is — just a hair behind the beat but rigidly so, with the result that the time has a stiff-legged, compulsive quality. The beat doesn't flow but jerks forward in a series of spasmodic leaps, creating a climate of nervous intensity that was peculiar to the era. Either the soloist jumps or he is fried to a crisp on the spot.

As a leavening element there was Sonny Clark, equally intense, but more generous and forgiving in his patterns of accompaniment. He leads the soloists with a grace that recalls Count Basie; and his own lines, With their heartbreakingly pure lyricism, make him the hard bop equivalent of Duke Jordan.

The ensemble sound of the band, a relatively uncommon collection of timbres heard elsewhere on Coltrane's and Johnny Griffin's first dates under their own names, gives the album a distinctive, ominous flavor; but this is essentially a blowing date.

Art Farmer, for my taste, never played as well as he did during this period, perhaps because the hard bop style was at war with his deadening sense of neatness. Possessing a musical mind of dandiacal suavity coupled with the soul of a librarian, Farmer usually sounded too nice to be true. But this rhythm section puts an edge on his style (as it did a few months later on the "Cool Struttin'" date); and I know of no more satisfying Farmer solo than the one preserved here on "Getting Into Something," where he teases motifs with a wit that almost turns nasty.

Adams' problem has always been how to give his lines some sense of overall design; and too often the weight of his huge tone hurtles him forward faster than he can think. But when the changes and the tempo lie right for him, Adams can put it all together; and here he does so twice, finding a stomping groove on "Getting Into Something" and bringing off an exhilarating doubletime passage on '"East of Brooklyn."

As for the leader, rather than describing each of his solos, it might be useful to focus first on a small unit and then on a larger one.

On the title track, Mobley's second eight-bar exchange with Jones is one of the tenorman's perfect microcosms and an example of how prodigal his inventiveness could be. A remarkable series of ideas, mostly rhythmic ones, are produced (one might almost say squandered) in approximately nine seconds. Both the relation of his accented notes to the beat and the overall pattern they form are dazzlingly oblique; and the final whiplike descent is typically paradoxical, the tone becoming softer and more dusty as the rhythmic content increases in urgency. In effect we are hearing a soloist and a rhythm player exchange roles, as Mobley turns his tenor saxophone into a drum.

On '*East of Brooklyn" Mobley gives us one of his macrocosms, a masterpiece of lyrical construction that stands alongside the solo he played on "Nica's Dream" with the Jazz Messengers in 1956.

"East Of Brooklyn" is a Latin-tinged variant on '"Softly As in a Morning Sunrise," supported by Clark's "Night in Tunisia" vamp. Mobley's solo is a single, sweeping gesture, with each chorus linked surely to the next as though, with his final goal in view, he can proceed toward it in large, steady strides.

And yet even here, as Mobley moves into a realm of freedom any musician would envy, one can feel the pressure of fate at his heels, the pathos of solved problems, and the force that compels him to abandon this newly cleared ground.

In other words, to "appreciate" Hank Mobley, to look at him from a fixed position, is an impossible task. He makes sense only when one is prepared to move with him, when one learns to share his restlessness and feel its necessity.

Or, as composer Stefan Wolpe once said. '*Don't get backed too much into a reality that has fashioned your senses with too many realistic claims. When art promises you this sort of reliability drop it. It is good to know how not to know how much one is knowing."

— Larry Kart

Original session produced by ALFRED LION

Produced for release by MICHAEL CUSCUNA

Recirdng engineer: RUDY VAN GELDER, VAN GELDER STUDIOS, NEW JERSEY

Remix engineer: TONY SESTANOVICH

Recorded on October 20, 1957

Cover photo: K. ABE

75th Anniversary CD Reissue Notes

Between November 1956 and October 1957, Hank Mobley recorded an amazing seven albums for Blue Note. Each had a different cast and different instrumentation. They were all exceptional sessions, but only the first five were issued at the time. "The Hank Mobley Quintet featuring Sonny Clark" and "Poppin"' sat in the vaults until the '80s.

"Poppin"' is a wonderful session. Mobley was really on a roll as a composer and small group arranger that year. His three originals here are definite highlights and the blend of Mobley's tenor, Pepper Adams' baritone and Art Farmer's trumpet is a fresh, unique sound.

The secret ingredient on this session is the rhythm section of Sonny Clark, Paul Chambers and Philly Joe Jones. Just a week earlier, they had made the explosive Blue Note masterpiece "The Sonny Clark Trio". At this point in time, you could not find a more sensitive or harder swinging rhythm section than these three men.

Michael Cuscuna

No comments:

Post a Comment