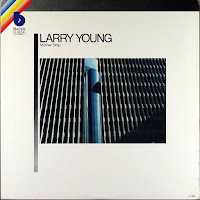

Larry Young - Mother Ship

Released - 1980

Recording and Session Information

Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, February 7, 1969

Lee Morgan, trumpet; Herbert Morgan, tenor sax; Larry Young, organ; Eddie Gladden, drums.

553 tk.2 Visions

554 tk.6 Love Drops

555 tk.8 Trip Merchant

556 tk.12 Mother Ship

557 tk.13 Street Scene

Session Photos

Photos: Francis Wolff

Track Listing

| Side One | ||

| Title | Author | Recording Date |

| Mother Ship | Larry Young | February 7 1969 |

| Street Scene | Larry Young | February 7 1969 |

| Visions | Larry Young | February 7 1969 |

| Side Two | ||

| Trip Merchant | Larry Young | February 7 1969 |

| Love Drops | Larry Young | February 7 1969 |

Liner Notes

LARRY YOUNG

Born in Newark on October 7, 1940, Larry Young Jr began studying jazz and classical piano at a very early age. Bud Powell served as his first inspiration and his model for modern jazz. But it was not until 1959 that he began to take music seriously as a full time endeavor and as a means of self-expression.

Larry's shift of emphasis from piano to organ occurred circumstantially at the age of 14, when his father opened a Newark club that had an organ in it. Larry became immediately fascinated by the instrument and its many possibilities. He was in no way attracted to the stylized, cliche-ridden approach to the organ as a popular funk jazz vehicle. In fact, he later remarked that "it's a shame that so many organists are so commercial. This instrument can do anything and can be used so many ways with other instruments. I keep hearing so many things that I can do."

During the late fifties, Larry jammed with visiting jazz dignitaries and woodshedded with such local luminaries as Woody Shaw and Herbert Morgan. He worked a number of R&B gigs with Jimmy Ruching and others. But his jazz credentials officially began with a steady job in Lou Donaldson's group and a record date with Jimmy Forrest.

From 1960 to 1962, he made three albums as a leader for Prestige, although he was still in the process of developing his ideas and his identity He also worked in New York with Hank Mobley, Kenny Dorham, Tommy Turrentine and Johnny Coles. Newark, which had given us Mobley and Wayne Shorter, was at this time nurturing a new breed of creators with Larry, Shaw, Herbert Morgan, Tyrone Washington, Grachan Moncur and Eddie Gladden among them.

In September of 1964, Larry played on Grant Green's Talkin' Bout with Elvin Jones on drums. That trio became the rhythm section for Larry's first album Into Something with Sam Rivers and two more Grant Green albums Street Of Dreams with Bobby Hutcherson and / Want To Hold Your Hand with Hank Mobley, all on Blue Note and all recorded within a seven month time frame.

Inspired by the music of John Coltrane and Cecil Taylor, Larry began to further test the capabilities and limits of the instrument with which he had chosen to challenge himself. He developed a strong friendship with Coltrane, who was fascinated by Larry's conversion to the principles of the Moslem faith (Larry would later use his Moslem name Khalid Yasim on some occasions). Larry would often visit the saxophonist at his Long Island home where they would play duets for hours. Sadly, no documentation of those musical encounters exist.

On November 10, 1965, Larry recorded his second Blue Note album. The instrumentation: organ, trumpet, tenor sax and drums. The cast: Larry, Woody Shaw, Joe Henderson and Elvin Jones. That album Unity remains a groundbreaker and an unheralded classic to this day. The material and the performances were exceptional. Especially Woody Shaw's The Moontrane and the organ-drums duet of Monk's Dream.

This album was and still is influential among musicians in many circles. But at the time of release, it wasn't exactly a runaway smash. Contemporary music fans resisted the sound and preconceptions of the organ, and the typical organ fan didn't want to hear anything new. All of this, of course, left Larry betwixt and between and tragically underappreciated.

Larry had a sense for voicings and a touch that had previously been thought only possible on the piano. Yet he was a total organist, whose feet could pump out an extraordinary bass line independent of his hands and who used the tonal characteristics and effects that were unique to the instrument. He literally redefined the organ without denying an iota of its identity. With the album Unity, Larry demonstrated that he was mentally and physically equipped to translate his own ideas and the new language of jazz through an instrument that was sinking in the quicksand of cliches and audience grabbing techniques. The great masters like Jack McDuff and Jimmy Smith were still going strong and new talents like Don Patterson, John Patton and Freddie Roach were making their presence felt. But the market was overrun with moderately successful, second generation, third rate chitlin pumpers. And it was Larry Young that offered a way out of all that.

Grant Green in 1964 told Nat Hentoff, "One thing about Larry Young is that he is really an organist. He knows that instrument, and furthermore, unlike some organ players in jazz, Larry never gets in your way. On the contrary, he keeps building in and around what you are doing while always listening so that his comping is always a great help. He's much more flexible than organists usually are. And that makes it possible for him to comp specifically for each different player. Man, he even comps in a particular way for drums. Another thing is that Larry is always identifiable right away. You know it's him. It's his sound, his imagination and the way he creates melodic lines. His sense of melody is very fresh and very much his own."

Larry continued to record an album of his own music each year for Blue Note: Of Love And Peace in 1966, Contrasts in 1967, and Heaven On Earth in 1968. Each album was different, offering interesting repertoire and unusual instrumentation as well as a variety of creative musicians that included James Spaulding, George Benson, Eddie Gale, Byard Lancaster and Tyrone Washington.

He made his last Blue Note date on February 7, 1969, and it is the album that you now hold in your hands, released for the first time some 11 years after the recording. The instrumentation parallels Unity, but this time it's Lee Morgan, Herbert Morgan (no relation) and Eddie Gladden. About the late Lee Morgan, little need be said. He was a master, an individual, a creator. His total command of the past and own foresight into the future and uncanny spontaneity made him a perfect companion for Larry.

Herbert Morgan, who had been playing with Larry since their teenage years, was also featured on Of Love And Peace, Contrasts, and Heaven On Earth. Larry told Nat Hentoff, "Herbert Morgan, who grew up in Newark as I have, has been like a big brother to me, I remember when I was about thirteen and trying to stabilize my energies so that they could be used constructively, he helped me spiritually and musically. He embraced Islam before I did. He never left Newark much. He stayed here and grew." And from all reports, Morgan is still in Newark and still actively growing on his instrument.

Eddie Gladden has been a stabilizing influence and fiery inspiration for scores of groups in the New York and Newark area. He has recorded with Richie Cole, the late Eddie Jefferson, Ronnie Cuber and Bill Hardman among others in recent years. In the mid seventies, he was with the Horace Silver Quintet. And in the spring of 1977, he joined Dexter Gordon's quartet of which he is still a member. Eddie had recorded with Larry on Contrasts and Heaven On Earth, each of which offered one astonishing organ-drums duet.

This session features five fine Young originals and marked a growth in style that foreshadowed his later work with Tony Williams and Miles Davis. Listen especially to Larry's sense of dynamics and the unique sound that he extracts with a slowly rotating Leslie. His use of space over Gladden's rapid fire eight note ride on Mother Ship is fresh and disarming. Herbert Morgan's tenor solo locks in with the drums, while Lee Morgan probes his way over the rhythm with an effective half time stance.

Street Scene is funky, but on its own terms. Larry's solo is the highlight and conveys a feeling of true rejoicing.

Visions is a three part, 24 bar tune that is repeated twice before the solos burst forth. Eddie provides an eighth note, double time feel to the pulse. This sort of pulse and the long exposition are characteristic of Miles' music circa 1967. But this music is Larry Young all the way.

Trip Merchant also has elements that Larry and Miles shared at the time. Eddie rides a smooth, irresistible double time rhythm with a casual, but fully felt backbeat and those occasional, appropriate drum explosions. Larry is the prince of darkness here, weaving a solo with long, spacial, dark tones that logically spiral up into a tour de force. Lee Morgan leaps into the thick of things with his finest solo of the date, followed by a crisp and empathetic tenor solo from Herbert.

Love Drops is not the sentimental ballad that the title might suggest, but rather a solid, muscular jazz samba, performed with conviction and verve.

It might have been Larry's lack of public acceptance or an occasional fluff in the ensemble statements or the changing climate at Blue Note that caused this last date to remain unheard all these years. But the music remains fresh and vital. And its importance has increased, sadly enough, with the deaths of Larry and Lee.

Soon after this date, Larry would help to change the face of music as one third of Tony Williams' Lifetime with guitarist John McLaughlin. This trio was the first and, without a doubt, most honest and creative ensemble in fusion music. They spawned many imitators, including McLaughlin's own Mahavishnu Orchestra. Yet nothing matched the energy, excitement, dynamics, personality and creativity of Lifetime. Fusion became a sterile, predictable, manufactured form of what was meant to be startling and revolutionary. And everyone went to the bank, except Larry and Tony.

Larry also recorded a still unissued 15 minute jam with Jimi Hendrix in the same year and participated in Miles' Bitches Brew. In the early seventies, he recorded with John McLaughlin and Carlos Santana and made another album of his own for the definct Perception label with Pharoah Sanders among the sidemen.

In the middle of the decade, while still freelancing on the jazz scene, he tried to enter the funk sweepstakes, making two misguided albums for Arista. The albums didn't sell, which left Larry baffled and frustrated. He could not understand why musicians of far less ability and vision were so successful, while his efforts in the same idiom were not. More than once, I tried to explain that those others of lesser talent meant what they were doing while he was only intellectually trying to reproduce it. But Larry's personal frustration was never to be abated. He knew his worth, his foresight and his innovations, and that made his lack of recognition all the more disheartening.

He spent 1977 gigging with Houston Person, Jimmy Ponder and others, as well as leading his own group with tenor saxophonist Buddy Terry and drummer Joe Chambers. That phase is his work culminated with a duet album with Chambers for Muse Records.

On Tuesday, March 28, 1978, Larry's wife gave birth. His rather lucrative deal with Warner Bros. Records was finalized. And he was to open that night at a New York club with his new band. But Larry lay that afternoon in a hospital bed. And on Thursday, March 30, Larry Young died a needless death, a victim of the widespread disease known as hospital negligence and incompetence.

Larry was a wise, kind and loving man whose imposing stature was betrayed by his gentleness. He was a versatile, inventive and singular musician. We will miss the man and his music very much.

—Michael Cuscuna

No comments:

Post a Comment