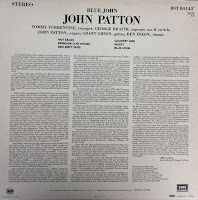

John Patton - Blue John

Released - 1986

Recording and Session Information

Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, July 11, 1963

Tommy Turrentine, trumpet #2; George Braith, soprano sax, stritch; John Patton, organ; Grant Green, guitar; Ben Dixon, drums.

tk.3 Blue John

tk.14 Nicety

Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, August 2, 1963

George Braith, soprano sax; John Patton, organ; Grant Green, guitar; Ben Dixon, drums.

tk.16 Hot Sauce

tk.20 Bermuda Clay House

tk.34 Dem Dirty Dues

tk.36 Country Girl

Track Listing

| Side One | ||

| Title | Author | Recording Date |

| Hot Sauce | George Braith | 02 August 1963 |

| Bermuda Clay House | George Braith | 02 August 1963 |

| Dem Dirty Dues | Grant Green | 02 August 1963 |

| Side Two | ||

| Country Girl | John Patton | 02 August 1963 |

| Nicety | Ben Dixon | 11 July 1963 |

| Blue John | John Patton | 11 July 1963 |

Liner Notes

The dedicated Blue Note collector will recognize Blue John as one of those fabled albums visualized tantalizingly on the jackets of issued LPs of the early sixties but which never achieved record store reality. Blue John approached substance to the point where Duke Pearson assumed its existence and discussed some details of the mirage in his notes to Big John Patton's third completed album The Way I Feel (BST 84174). Now at last you have the mythical beast (BST 84143) in your hands, and a good-hearted creature it is too.

John Patton had been introduced to Blue Note by that noted talent scout Lou Donaldson and featured by him on The Natural Soul (BST 84108) from May 1962. At the next session, the wonderful Good Gracious! album (BST 84125), Donaldson had dedicated a piece Bad John to the organist. And of course Alfred Lion knew a good thing when he heard it, signing John as leader for a period that would extend from Along Came John (BST 84130) through eight issued LPs up to Accent On The Blues (BST 84340) of August 1969.

Following the emergence of Jimmy Smith as a convincing purveyor of modern jazz on the instrument, a plethora of organists appeared on the scene, occupying niches in the cramped taverns of major cities across the country. For the most part their styles represented various compromises between the post-bop manner of Smith and the earlier jump-swing approaches of Milt Buckner, Wild Bill Davis and Bill Doggett. Indeed organ-guitar-sax groups held sway in clubs through the first half of the sixties, not by coincidence at a time when the jazz avant-garde was bursting on to the scene; how these two apparently divergent musical idioms both had their roots firmly planted in the blues is a story for another context. The seventies saw a reversal of fortunes, first for the goodtime organ bands as the club scene drained away, then for the more demanding forms of the new music. There remain now only a few hardy survivors of these sixties styles pursuing the pure idioms. For organ afficionados the names of Smith, Groove Holmes, Jack McDuff at al. still are there to be read, but others have been eclipsed. Who now remembers 'Baby-Face' Willette, whose Face To Face album (4068) was perhaps the ultimate classic of the sax-organ genre? For this writer two particular favorites of the period have vanished from the national scene: Larry Young, the most explorative of organists (always excepting the protean Sun Ra), taken too soon, and 'Big' John Patton, fortunately still active and hopefully on the brink of a resurgence of recognition.

John Patton was born into the productive musical ferment that was Kansas City, on July 12, 1935. Though his mother taught him the scales and how to read, and his cousin Lemuel "used to come by the house and show me little things," he regards himself a largely self-taught pianist (John's first instrument); "You know swinging Kansas City...automatically you'll try to play some blues, and really I've always wanted to play jazz. I'd try to get in the clubs on 12th Street...I wasn't old enough...I heard Dinah, Jay McShann, Marvin Patillo, a very good drummer...I went to school with Donald Dean, a drummer who later worked with Les McCann. There were little gigs at school and I was working a bit with my cousin; we went to that Wyatt Earp town..."

Not unfamiliar Kansas City memories but..."When I came out of high school I, well, like everybody, wanted to get out of my hometown. My brother was at Howard University, and I came up to Washington and got a job in a service station, while trying to play locally. I met a lot of musicians through the Howard Theater. I would go backstage and I met Lloyd Price, who was looking for a piano player. Someone told him I was in town and I had an audition. He asked me to play the introduction to Lawdy, Mis Clawdy. I played that and I had the gig.

While Patton's work with Price was limited to rhythm chores, Lloyd's commercial success led to an enlargement of the band and the opportunity to interact with musicians of wider experience. Also, some of the clubs they played had an organ: "I had a chance to turn it on and play it to see what it felt like...it was exciting, but when you play a piano then playing organ is something altogether different. Eventually musicians were saying 'why don't you play organ, man, 'cause you got this good bass line.' Ben Dixon, whose people used to live in the area, told me to go ahead and turned me on to Jimmy Smith's stuff. When I started to play organ I didn't know about Milt Buckner, Bill Davis...I had heard Bill Doggett because of the honky tonks. It didn't mean anything to me at that time, I was listening to piano players and Hampton Hawes, Horace (Silver) and Wynton Kelly were my favorites."

"My break point was when I left Lloyd in 1959, after five years, and moved to New York, where I met all the giants. I hung out with Ben, Calvin Newborn, Grant Green, Tommy Turrentine, George Braith, Kenny Dorham, Bobby Timmons and a lot of musicians who worked with Lionel Hampton (including a special friend, the undervalued but remarkable tenor saxophonist Fred Jackson). I was staying at the Flanders Hotel, downtown, which was a center for many musicians."

Patton learned much from these contacts and willingly recognizes this debt. The first few years in the New York/New Jersey coast area were spent in transforming the pianist to organist.

"Ben Dixon was my mentor...he was a hell of a reader and did a lot of writing. He liked Max (Roach) for his technical ability and melodic playing, but Philly Joe Jones, who was his idol, for the flair. Ben was always trying to create different beats, he could really swing and was so uninhibited about 2 and 4; he was like the drummers now, he would utilize the sock cymbal and turn the cymbal beat around... just create his stuff. Very few of the musicians I have played with are as great musically and rhythmically."

"Grant (Green) was dynamite as far as I was concerend. I also learned a lot from him, particularly as a soloist. He was a hell of a soloist...the way he played single lines was really unbelievable. We rehearsed quite a bit and composed tunes together and later we worked together for three and a half years, booking ourselves across the states, St. Louis...Kansas City. Indiana...Chicago...all the East Coast."

Grant, Ben and John were the team that enhanced those Lou Donaldson sessions (for Blue Note) mentioned above, and trumpeter Tommy Turrentine, also a member of the altoist's retinue, had made The Natural Soul date. Patton admired Turrentine's sound and used to woodshed with him in rented rehearsal halls around 47th Street or at George Braith's studio.

"I met George Braith when I was living on 47th and he was down there too. He played tenor (how well can be heard on Braith 's own Extension [BST 84171), but his baby was the "Braithophone' (Saxophones braced together and played that way). He had a studio we used to go to and he would put both horns in his mouth...this was before he had them connected. He was a good musician, he could hear that harmony."

The period in New York was clearly a highly stimulating one, with extensive interactions amongst the musicians and Patton's reminiscences are a pleasant counter to the not uncommon reports of rivalries and exclusive behavior by some jazz musicians. The interactions extended across what might be regarded as stylistic hurdles: "I used to go to Sun Ra's down by the Five Spot all the time and play with John Gilmore, Marshall Allen, Clifford Jarvis (who was out on the road with me and Grant for about a year)... and you hear Sun Ra play and you say 'wait a minute'..."

John's later collaborations with Grachan Moncur III will bear witness to his open frame of mind. But the blues have priority, and in Blue John we have an idiomatic document of the times and the circle of friends. Here we have tunes by Patton, Dixon, Green and Braith, who also serves up some early examples of his binary sax playing. As garnishing, Tommy Turrentine pops up on the last two pieces.

While it should be unnecessary to give a blow-by-blow analysis of this card of blues or bluesy workouts, a few points can be made. First is the variety, particularly of rhythmic foundation, that is to be found in a rather restricted range of theme and tempo, reminding us of the leader's tribute to Ben Dixon and the comments of others on Patton's bass lines. This is enhanced in some pieces by the use of stop-time and breaks, venerable items of the jazzman's arsenal. Second is the clarity of the performances, which stems from the leader's avoidance of attempts at false climaxes that often swamp so many organ recordings. John's ability to differentiate the voices at the instrument's command and build single lines show a creative economy that probably stems from his taste in pianists.

We may also note the wonderful sound Grant Green drew from his electric guitar — witness the angelic entry on Bermuda Clay House with the faint quaver of vibrato that can render his most funky phrase lyrical. In addition to the two-sax tandems from Braith, we hear him single-voiced on the alto-like stritch in a fine solo on Bermuda, while the soprano breaks free for a couple on Blue John, and seems to chuckle gleefully at its independence. The trumpet leaps and tumbles brassily over somewhat sedate support on Nicety, invoking a few other musical idioms along the way; it would be good to hear more of Tommy T. these days.

Unfortunately the scene has changed since the time of these recordings. It is not so easy now to step out in the evenings and into some neighborhood tavern to refresh oneself in the truly goodtime atmosphere of a jazz style so well-represented by "Big" John Patton on this album. Apart from a few names, the organ groups became less the thing; in fact clubs with live jazz also became less the thing. Grant Green achieved some limelight and then was lost. Ben Dixon appears to have consciously withdrawn from the general jazz scene. George Braith's pan-pipes are not widely heard. And John Patton, now based in East Orange, N.J., though still active, does not work as much as he would wish. That the fire and taste are still there to be appreciated has been made quite apparent by his recent Soul Connection (Nilva 3406). But John, your music shouldn't be for collectors only (let alone those of unissued albums). Step out so more of us can partake of such spirit pleasing music again.

TERRY MARTIN

Jazz Institute of Chicago Archives

No comments:

Post a Comment