Johnny Coles - Little Johnny C

Released - February 1964

Recording and Session Information

Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, July 18, 1963

Johnny Coles, trumpet; Leo Wright, alto sax, flute; Joe Henderson, tenor sax; Duke Pearson, piano; Bob Cranshaw, bass; Walter Perkins, drums.

tk.8 Little Johnny C

tk.12 Hobe Joe

tk.21 Jano

Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, August 9, 1963

Johnny Coles, trumpet; Leo Wright, alto sax, flute; Joe Henderson, tenor sax; Duke Pearson, piano; Bob Cranshaw, bass; Pete La Roca, drums.

tk.4 Heavy Legs

tk.18 My Secret Passion

tk.22 So Sweet My Little Girl

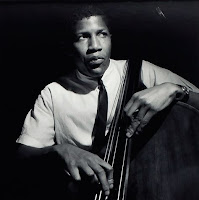

Session Photos

Photos: Francis Wolff

Track Listing

| Side One | ||

| Title | Author | Recording Date |

| Little Johnny C | Duke Pearson | 18 July 1963 |

| Hobo Joe | Joe Henderson | 18 July 1963 |

| Jano | Duke Pearson | 18 July 1963 |

| Side Two | ||

| My Sweet Passion | Duke Pearson | 09 August 1963 |

| Heavy Legs | Duke Pearson | 09 August 1963 |

| So Sweet My Little Girl | Duke Pearson | 09 August 1963 |

Liner Notes

MY first contact with Johnny Coles came early in 1959. Just after my arrival in the big city, I went to Birdland to hear the pure sounds of the modern jazz giants. As I was descending the stairs to sit in the “peanut gallery” (reserved for non-drinkers), I was greeted by the established sound of the Gil Evans orchestra, but attracted more so by the warm sound of the trumpet soloist. I paused on the bottom step staring in wide eyed amazement at a young man standing about five feet, three or four inches tall, leaning way back, and using much “body-english” to help emphasize each phrase he played. This little man, I learned, was John Coles.

The next tune was his spotlight number, Davenport Blues. It was a gas! He leaned even farther back, and used more “body-english” with his phrases, and his horn seemed to cry from the warmth that was within the very big soul of this little giant.

My next encounter was in 1960 while I was with the Art Farmer-Benny Golson Jazztet. We played a theatre date at the Howard ¡n Washington, D.C., and Johnny Coles was the featured soloist with the James Moody band. (He was with Moody five years.) I wondered why I hadn’t heard more of him before, because it was quite obvious that the music had been written and arranged around the way he plays. And he was truly “the sound” in both groups.

I learned that aside from playing and recording with Gil and Moody, he had worked with Eddie “Cleanhead” Vinson (John Coltrane and Red Garland were in the band), and with the Gene Ammons group. Also with Bullmoose Jackson, who at the time had Benny Golson, Todd Dameron, Jymie Merrill and Philly Joe Jones.

Remembering what I had heard at Birdland and at the Howard Theatre in D.C., I called Johnny to record with me, using two trumpets, the other being my good friend Donald Byrd. This began a very close musical relationship with Johnny that’s still in existence.

Earlier this year, I worked a Monday night gig with Johnny at Birdland. Blue Note’s Alfred Lion happened to be there and heard us ploy Little Johnny C. He liked it very much and thought it would be a good number to record. Mr. Lion and I talked this over, and eventually I was given the green light to prepare the session. Aside from the already chosen Little Johnny C., other music was needed to compliment the delicate way Johnny plays. This was no problem, because Johnny and I had been working together for more than a year, and during this period we came to know each other’s taste very well.

Little Johnny C. — the title tune, is an up tempo F Major blues. The first solo is by guest artist Leo Wright for five cookin’ choruses, followed by “Little Johnny C.” himself. With piano strolling the first two choruses, Johnny displays his ability to deviate from form by playing in several “other” keys without disrupting the context of pattern. Thirdly, Joe Henderson for four choruses, then piano and out.

Hobo Joe — written by Joe Henderson, is a Latin flavored B flat blues that goes to swing on the third and fourth blowing choruses. Johnny is first on the solo order, and here his versatility is most evident. He’s cool, aggressive and always in good taste. Leo makes his entrance reminiscent of the early Louis Jordan influence. “Hobo Joe” Henderson enters cool and remains cool throughout. For me, Henderson is the possessor of the freshest tenor sound around. And he too belongs to the Blue Note soulstation. He can be heard at length on his Blue Note album Page One (4140), as well as with Kenny Dorham on his album Una Mas (One More Time) (4127).

Jano — a nine bar tune, concludes the side. And here Coles is at his best. His knowledge of what to do with chords is amazing. Honorable mentions here for Bob Crenshaw’s sturdy bass lines and Walter Perkins’ unobtrusive fill-ins. My Secret Passion — This jazz waltz melody is prettily played by Johnny, after which he goes into a very engaging solo. Henderson’s development of phrases is unique, and Leo’s flute solo displays his versatility. Pete LaRoca replaces Walter Perkins on drums, and Bob Crenshaw remains solid as a rock.

Heavy Legs — a bright thirty-two bar tune presents Coles as pace-setter. Here he sounds like he did when I heard him with Gil Evans, only mellowed with age. He definitely sets the mood for what’s to follow. Joe Henderson comes through splendidly — the rhythm settles — Joe quotes “Isn’t It Romantic?” — and it certainly is! Leo ends his climactic solo, and Crenshaw and LaRoca steadily carry the romp thru the piano solo and the shout phraseology “heavy legs”.

So Sweet My Little Girl was written for my seven year old daughter, Cynthia. Johnny restricts himself to solo-melody duties, and I’m given the solo spot to play tribute to my little Cynthia. Johnny’s sound here is that of a proud parent serenading his own little daughter.

Such trumpet greats as Miles, Dizzy, Fats, Brownie, Kenny Dorham, etc., have all reached their own distinctive styles as a result of admiration and respect for other greats.

This respect and admiration did not give in to imitating, which, therefore gave them the unrestricted opportunity to discover their own individual potential.

Johnny Coles is a warm individual with a personal approach to each note or phrase he plays. A painter of very beautiful patterns. And after listening to him here, you’ll be able to distinguish his style from any of his contemporaries.

So, with the given permission to prepare this album, the original compositions contributed, piano accompaniment, and the writing of these liner notes, it gives me a great honor to pay tribute to such a big little giant as “Little Johnny C.”

—DUKE PEARSON

RVG CD Reissue Notes

A NEW LOOK AT LITTLE JOHNNY C

Trumpeter Johnny Coles is one of those extremely gifted yet little heralded musicians who are all too common throughout Jazz history, Duke Pearson's original liner notes list Coles's primary early affiliations, including his extended stays in James Moody's small groups (beginning in 1956) and the various studio and working orchestras of Gil Evans (from 1958), Coles played on two of the Evans/MiIes Davis albums on Columbia, and was Evans's Davis surrogate elsewhere. Shortly after the present recording session, Coles joined Charles Mingus and participated in Mingus's legendary 1964 European tour. He was in the first edition of Herbie Hancock's late-'60s sextet, a member of the Duke Ellington trumpet section during the last year of Ellington's life, and an appropriate choice for lead horn in the Tadd Dameron tribute band, Dameronia, that Philly Joe Jones led a decade later.

Coles was rarely found on the roster of any jazz label during his extended career. Little Johnny C is the second of only five albums that appeared with the trumpeter billed as leader or co-leader, and one of only five appearances on Blue Note in any capacity. In addition to containing Coles's most memorable recorded work under his own name, it is a testament to the affinity he shared with pianist/composer Pearson, The two-trumpet session that Pearson alludes to had been cut for independent producer Fred Norsworthy in 1962, and also featured the Bob Cranshaw-Walter Perkins rhythm team heard on the first three tracks here. (Cranshaw and Perkins were old familiars at this point, having been the MJT in the MJT + 3 quintet,) While Coles did not appear on any of Pearson's later Blue Note sessions, he was featured on two albums that the pianist cut for Atlantic in the mid-'60s, Honeybuns and Prairie Dog.

As well as Coles plays here (see the original notes for all necessary commentary on the trumpet solos), it would be fair to consider Pearson the unacknowledged leader of the album. Pearson was coming into his own as an essential part of the Blue Note team at this time, having raised his profile substantially with his composing and arranging on Donald Byrd's A New Perspective in January 1963. When Ike Quebec died that same month, Pearson assumed his duty as liaison/assistant producer the label, adding his superior writing skills to the mix. All of his contributions here reflect a bluesy lyricism that mirrored Coles's conception perfectly. Particular attention should be paid to "Jano" and "So Sweet My Little Girl," two compositions of unusual shape that, in diverse ways, reflect what some might consider an unexpected Thelonious Monk influence on Pearson's music.

In addition to the melodic frameworks, Pearson had a distinct idea in mind for the ensemble setting that would best serve Coles. It is a reduced version of a larger group that the pianist employed on a series of contemporaneous sessions that produced an Audio Fidelity album under the name of conga drummer Antonio Diaz Mena, (All six musicians heard on the first three tracks made the Mena dates.) Pearson obtained a djstinctjve sound by employing trumpet against two saxophones, with the doubling flute; it was a sound he liked well enough to reprise five days after the second of the present sessions, for the Blue Mitchell album Step Lightly that has Herbie Hancock on piano but Leo Wright and Joe Henderson returning to form the reed section, Wright, another overlooked talent like Coles, is best remembered for his 1959-62 stint with Dizzy Gillespie and his contribution to such classic albums as Gillespiana and An Electrifying Evening with the Dizzy Gillespie Quintet. One wonders what might have happened to Wright's reputation (or, for that matter, to James Spaulding's subsequent role as Blue Note's alto/flute double of choice) if economic circumstances had not forced Wright's relocation to Europe in 1964.

Joe Henderson's future as a jazz presence was much brighter. This was only his fourth Blue Note date, and the inclusion of a Henderson composition indicates that both his playing and writing were already attracting appreciation. "Hobo Joe" may not be Henderson's most challenging tune, but it captures the long-metered ambience of such future crossover hits as Lee Morgan's "The Sidewinder" and Horace Silver's "Song for My Father," both of which owe a degree of their success to Henderson's fiery tenor contributions. The primary story here, though, involves Coles and Pearson, two musicians with a common soul that turned this one-shot recording project into a timeless representation of their complementary talents.

— Bob Blumenthal, 2004

Blue Note Spotlight - January 2013

http://www.bluenote.com/spotlight/little-johnny-c-johnny-coles-on-blue-note/

Trumpeter Johnny Coles, born in Trenton, NJ in 1926, was an in-demand sideman from the 1950s to the 1970s. Though he got his start in R&B, he made a smooth transition to jazz, working with James Moody, Gil Evans (playing on Miles Davis’s Sketches of Spain) and Herbie Hancock, as well as returning to his roots with Ray Charles, and later on joined Duke Ellington’s orchestra and Art Blakey’s band. Perhaps his most famous role, though, was as trumpeter in Charles Mingus’s highly regarded 1964 sextet, which also featured reedists Eric Dolphy and Clifford Jordan, pianist Jaki Byard and drummer Dannie Richmond. Coles made few recordings as a leader, and only one for Blue Note—1965’s Little Johnny C. But his sharp, clear tone always made him stand out, and he played on several notable albums for the label during the 1960s.

Coles’ first Blue Note gig was on saxophonist Tina Brooks’ final session, in March 1961. The music wasn’t released until 2002, as The Waiting Game. It’s a punchy, swinging hard bop date featuring the two horns backed by pianist Kenny Drew, bassist Wilbur Ware, and drummer Philly Joe Jones. Coles and Brooks work well together, trading melodic, bluesy solos that showcase the lyricism that marked each man’s style. Brooks was a performer somewhat ill-served by the record industry; only one of his Blue Note albums, True Blue, was actually released during his lifetime, making him far better known as a sideman (working with Kenny Burrell, Freddie Hubbard, Jackie McLean, Jimmy Smith and others). But both he and Coles swing hard on The Waiting Game, particularly on opening track “Talkin’ About,” the forceful, yet romantic “Dhyana,” and the somewhat exotically flavored “David the King.”

In February 1963, Coles played on pianist Horace Parlan’s Happy Frame of Mind, alongside saxophonist Booker Ervin, guitarist Grant Green, bassist Butch Warren, and drummer Billy Higgins. Like The Waiting Game, it sat in the vaults for a while—it was originally released in 1976, under Ervin’s name, as Back From the Gig. Though it’s definitely grounded in the bluesy, soulful hard bop that was Parlan’s stock in trade, the album finds all the players stretching into more adventurous territory, along the line of many similar sessions Blue Note would record and release between 1963 and 1965, as they shepherded a number of “inside-outside” musicians, including Andrew Hill, Sam Rivers, and Bobby Hutcherson, among others. Like Lee Morgan’s Search for the New Land, Happy Frame of Mind offers the sound of players breaking their own self-imposed limits and uncovering rewarding new territory in the process.

The trumpeter next appeared on Green’s Am I Blue?, recorded in May 1963 with saxophonist Joe Henderson, organist John Patton, and drummer Ben Dixon. As its title suggests, this is an album suffused with a powerful, stoic melancholy, and Coles and Henderson serve as a superb chorus, punching in behind Green’s lead lines as though he was a blues or soul vocalist. When the trumpeter takes his first (brief) solo, on “Take These Chains From My Heart,” his tone is full, but somehow constricted, and his notes pierce the listener; it’s as though he’s trying to hold back tears. He plays in a similarly mournful style on the affecting “I Wanna Be Loved,” perfectly summing up the album’s overall feeling of sorrowful brooding. Am I Blue? is one of the great late-night, coffee-and-cigarettes albums in Grant Green’s discography, and Coles’ trumpet solos are one of the crucial elements of its success.

Coles recorded his sole Blue Note album as a leader at two 1963 sessions, held on July 18 and August 9. Little Johnny C was made with a mixture of well-known players—Joe Henderson on tenor sax again, Duke Pearson on piano, Bob Cranshaw on bass, Pete La Roca on drums half the time—and other, slightly more obscure musicians, like alto saxophonist Leo Wright and drummer Walter Perkins, who plays on the other half of the album. In many respects, this was as much Pearson’s session as Coles’; he wrote five of the six tunes, and did the arranging. Still, despite Pearson’s sweetly bluesy soloing on the title cut and elsewhere, it’s a horn-driven album, and the interplay between Coles and Henderson in particular is fierce and joyous, the two men trading turns in the spotlight at great speed and with sharp clarity of musical purpose.

One of Johnny Coles’ greatest recordings was lost to history for over four decades. Charles Mingus’s 1964 sextet barely got anything on tape other than European bootlegs and a single concert at New York’s Town Hall, but in 2007, Blue Note released Cornell 1964, a concert that was not only previously unreleased, but forgotten by all but those who’d been present at the time. The radically extended workouts the band indulged in—two tracks, “Fables of Faubus” and “Meditations,” run a half hour each, and three others, “Orange Was the Color of Her Hair Then Blue Silk,” “Take the ‘A’ Train,” and “So Long Eric,” are more than 15 minutes long each—provide plenty of room for lengthy soloing. Coles makes the most of his time in the spotlight, particularly on “Fables” and, of all things, a version of “When Irish Eyes Are Smiling,” a tune that elicits audience laughter as it begins, but wild applause after the band, and the trumpeter in particular, have wound their way through it.

Coles only appeared on one other session for Blue Note—he was part of the expanded ensemble that recorded Herbie Hancock’s The Prisoner. But his unique voice and style on the horn always made him a standout player, no matter the session or material.

No comments:

Post a Comment