Don Cherry - Symphony For Improvisers

Released - 1967

Recording and Session Information

Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, September 19, 1966

Don Cherry, cornet; Leandro 'Gato' Barbieri, tenor sax; Pharoah Sanders, tenor sax, piccolo; Karl Berger, vibes, piano; Henry Grimes, Jenny Clark, bass; Edward Blackwell, drums.

1786 tk.2 Symphony For Improvisers: Symphony For Improvisers

Symphony For Improvisers: Nu Creative Love

Symphony For Improvisers: What's Not Serious

Symphony For Improvisers: Infant Happiness

1787 tk.5 Manhattan Cry: Manhattan Cry

Manhattan Cry: Lunatic

Manhattan Cry: Sparkle Plenty

Manhattan Cry: Om Nu

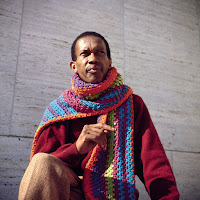

Session Photos

Photos: © Francis Wolff/Mosaic Images https://www.mosaicrecordsimages.com/

Track Listing

| Side One | ||

| Title | Author | Recording Date |

| Symphony for Improvisers: | Don Cherry | September 19 1966 |

| Symphony for Improvisers | ||

| Nu Creative Love What's Not Serious? Infant Happiness | ||

| Side Two | ||

| Manhattan Cry: | Don Cherry | September 19 1966 |

| Manhattan Cry | ||

| Lunatic Sparkle Plenty Om Nu |

Liner Notes

The New Music is no longer new, not as a phenomenon: It has been, after all, more than ten years since the John Coltrane sound was first heard in New York. Cecil Taylor recorded Jazz Advance on the now defunct Transition label in early 1957, and Ornette Coleman and Don Cherry cut Something Else one year later. Since then, a lot has happened to the New Music and to the New Musicians. The Music has grown into the biggest sound in the world, a force that moves all weights, the superior “serious” music in the Western world because its roots, out of Africa, are out of the East; a virile new form in a century which discards its old forms like used up Kleenex tissues.

The number of New Musicians has likewise grown. They number a few hundred, and that numbers swells with the birthrate. The Music is national and international, as the enclosed record will attest. Here are assembled musicians from France, Germany, Argentina and from places as far apart in the U.S. as New York, Philadelphia, New Orleans, Little Rock and Los Angeles. ‘It is not uncommon to run into teenaged musicians from small towns in the midwest who are very advanced indeed, knowledgeable about the music and its heritage, copying such old masters as Sonny Murray or Eric Dolphy, fluent in music that swings but has no heat that you could count, is structured but has little melodic content, has far more dissonance than consonance in its sound.

Typically, some token and belated recognition is now forthcoming, several years after the fact. There are still only a handful of jobs for every hundred musicians, and the air space devoted to the New Music is still negligible, but the strength of the Music is undeniable, and at last a few national magazines have devoted some small space to it.

A clue of the strength, depth and breadth of the New Music is the number of musicians who have grown to maturity in it. Four such musicians are represented here: Don Cherry, Henry Grimes, Pharaoh Sanders and Ed Blackwell all have handled several jazz disciplines at various points in their careers but have spent most of the last decade of their still young lives working in the milieu of the New. Each has that big, mature ear that makes for virtuosity in a jazzman; each is a leader on his instrument, influencing in technique and style not only the younger musicians, but also their contemporaries and those of the antecedent generation who want to keep their tradition alive in these times. Their influence is that pervasive.

To make an admittedly dangerous generalization, I think it is fair to say that Ed Blackwell is the leader of one of the two important schools of New drumming. Sonny Murray leads the other and there are, as there should be, several beautiful drummers both in between and someplace else. "Everything is everything," say the musicians, "everyone is everywhere." Murray and his progeny want to dissect time; Blackwell and his folk want to elaborate on it. Here, in Don’s Symphony for Improvisers, Blackwell is in his natural environment, a brilliant, pulsating, undulating music that swells and ebbs, changes the volume and shape of its sound. One is tempted to picture Ed's hands as the energy and flow of a mountain stream, but that would be a bit too much, wouldn’t it? But there it is, that patented unpressed flow of Blackwell’s, that incredibly correct attention to detail, that adaptability which only the fastest and most disciplined of hands can maintain. Pushing upward into the strong pulse of Henry Grimes and his able French assistant, Jenny Clark, Blackwell makes this rhythm section something other than an accompanying metronome. “He plays rhythm rather than time time,” says Don.

Henry Grimes is thought by his contemporaries to be the premier bassist of the day. “Henry’s a giant,” said Cecil Taylor, a man who dispenses praise with exceptional stinginess. Grimes, like Cherry, has been in the vanguard of jazz bassists for ten years now, and every day has been a day of growth. His intelligence, strength and virtuosity sustain, from the first chord to the last, the impeccable vitality of this record.

Pharaoh "Little Rock" Sanders has, in my opinion, taken over the late Eric Dolphy's role as the torch-mouthed screamer of the reeds. He somehow manages to translate to alto and piccolo that immense vocabulary of manipulated sound we came to admire so much on tenor saxophone. Ironically, two years with John Coltrane, pater familias of contemporary saxophone players, has finished off the Coltrane sound in his horn and brought out the Pharaoh sound. His skill in pulling from the horn unheard of sounds in articulate order at a hundred miles an hour defies description. See him in person the next time he’s in your neighborhood, and you’ll be shocked, I’m sure, at what he can do. He absolutely kills me is all I can say.

We heard Leandro "Gato" (that’s an Argentinian name for you) in Don's first recorded extended work, Complete Communion (Blue Note 4226) and he is as germane on this recording as on the other. Gato’s is the big open sound; the long, almost legato wail. He admittedly got to sound this way by working with Don and some of the other New Musicians in various parts of Europe, as did Karl Berger and Jenny Clark. It was during this time that some of the tunes used in this work were written, tunes like Manhattan Cry and Lunatic (“that’s what they called us when they first heard us in Europe: lunatics.”) If the performances of Barbieri, Clark, and Berger seems intimate with this most difficult music, the reason is that these men were all in Don’s “European” group, and, despite severe linguistic difficulties, they worked closely with him over a period of months.

All of which says something about Cherry’s approach to the related problems of composition and group leadership: when he hears a tune, he hears specific voices singing it. He also hears his tunes, and the improvisational implications of those tunes, connecting into the fabric of a larger form; hence a Symphony For Improvisers. It is also to be considered in studying the form of this work and the use of the word “Symphony” in its title that the LP has become a jazz form in itself in the last decade, with musicians planning a forty minute presentation of improvisation as an enduring work, as opposed to the inhibiting brevity of the “single,” "and the throw-away nature of unrecorded nightclub work.

In Symphony For Improvisers as on Complete Communion, Don has carried this idea of the LP as a form to its logical conclusion, and thereby he has made one of those sudden innovations that jazz history is so full of. He has done this by eliminating the separating hiatus between the tunes so that there is no loss of improvisational energy, leaving the record as a unit, intact and self-sufficient, and by organizing the sound so that the various climaxes, collective, solo, duet, etc., come out of the improvisation in such a coordinated way that the piece, in toto, is balanced.

Certainly others have been working with the long form in jazz. Cecil Taylor for one, often in live performance, moves from one tune to the other without an interval, and several of the New Musicians have recorded LPs wherein extended improvisation takes up at least one side of the record (Ornette Coleman and John Coltrane have each devoted two sides of an LP to one long “free” improvisation). But Don Cherry has, with Complete Communion and Symphony For Improvisers, applied his excellent composer’s ear to more integral music. One way of doing this was to reintroduce the thematic material at strategic points in the improvisation: “we improvised from the flavor of the tune, from the mode, and the themes come back from time to time, so that it’s definitely one thing that we made, not eight.”

All of this is typical of Don Cherry’s work, not only with his own groups but also with the major saxophonists of the day: Coleman, Coltrane, Rollins, Ayler, Sanders, Shepp, Brown and so on. For several years now he has been the leading trumpet stylist of his generation, a remarkably consistent performer who always propels those fortunate enough to work with him to meet his own standard of excellence. In an era so dominated by saxophonists that brass sometimes seems to be on the verge of extinction, Don, like Miles Davis, has shown the saxophonists up for what they cannot do. When the saxes are firing, Don is slurring; when the alto is so high above the register that it sounds like a whistle, Don is imitating the human voice in song; when the tenor is making some flipped out confessional, Don is making brilliantly understated jokes. Such wit and subtlety are rare in today’s music, which makes Don Cherry a big and vital man.

by A.B. Spellman

RVG CD Reissue Liner Notes

A NEW LOOK AT SYMPHONY FOR IMPROVISERS

Don Cherry recorded all three of his Blue Note albums in the space of 10 months. This, the middle volume, represents both the most ambitious of the three through its use of a septet, and the most complete representation to that point of the international partnerships that would define the final three decades of the cornetist's career.

As A. B. Spellman indicates, Cherry established himself at the start of his recording career through supporting and collaborative roles with the leading saxophone innovators of the period: Ornette Coleman (beginning in 1958), John Coltrane (in two 1960 sessions ultimately released by Atlantic under their joint leadership as The Avant-Garde), Steve Lacy (1961), Sonny Rollins (1962), Archie Shepp and John Tchicai (1963—64, in the New York Contemporary Five), and Albert Ayler (1964). Beginning with his term in the Rollins quartet, Cherry toured frequently in Europe where he found greater acceptance for the music that, at the time, was still referred to as the New Thing. By the beginning of 1965, he had established his own working quintet, an assemblage featuring Argentinean saxophonist Gato Barbieri, German vibist Karl Berger, French bassist Jean-Francois Jenny-Clark, and Italian drummer Aldo Romano. During the early months of the year, the band made its first recordings in Paris, a series of connected themes in the manner of the present album under the title Togetherness.

After more work on the continent, including a concert recorded with composer/pianist George Russell, Cherry returned to the U.S. late in 1965 with Barbieri in tow. It was then that Cherry linked up with Blue Note and recorded Complete Communion, a quartet session where he and Barbieri were joined by two musicians who would contribute to each of Cherry's albums for the label, Henry Grimes and Ed Blackwell. Then, early in 1966, Cherry returned to Paris and reassembled his European quintet. All members save Romano were present Stateside for this September session, and are joined by Grimes, Blackwell, and Pharoah Sanders, who also appeared with Cherry two months later on the quartet album Where Is Brooklyn?

Cherry's Blue Note recordings reflected the sum of these experiences, and revealed a previously underexposed compositional voice influenced by both Coleman (most clearly on " Infant Happiness" on the present session) and Ayler (the anthem-like "What's Not Serious," with its echoes of a beer hall, is a good example). Symphony for Improvisers stands out among the three with its expanded ensemble (with vibes in place of piano, å la Bobby Hutcherson on a body of Blue Notes from the period). Most memorably, the preceding Complete Communion and Symphony for Improvisers link individual pieces into suites that covered entire sides of a 12-inch LP.

At no point on the album are either the two tenors or the two basses heard together, and transition points are often imprecise. Sanders and Barbieri are together throughout the four movements of "Symphony for Improvisers," but Pharoah plays piccolo exclusively. The following synopsis, from Alfred Lion's original session notes, attempts to cite benchmarks:

"Symphony for Improvisers," with Grimes on bass, begins with an invocation that leads to an up-tempo open form with solos by Sanders on piccolo, Cherry, Berger, and Barbieri, followed by exchanges with the full ensemble in the same order. Five minutes in, Cherry signals the start of "Nu Creative Love" by triggering a diminuendo that resolves to a medium straight-ahead beat and a round of solo statements by Berger and the leader. Jenny-Clark is the bassist here and most probably throughout the next two titles. The waltz "What's Not Serious" is launched around the 9-minute mark as a feature for Blackwell. Three minutes later the childlike "Infant Happiness" restores the original tempo and finds Cherry, Berger, Sanders on piccolo, Blackwell, and Cherry soloing.

"Manhattan Cry" opens as a ballad for cornet, with Berger accompanying on piano and Jenny-Clark again on bass. After solos by Berger and Barbieri, the saxophonist and Cherry introduce "Lunatic, " a medium-tempo open form with solos by Cherry, Berger (back on vibes for the duration), and Barbieri. Blackwell's drums provide the transition to "Sparkle Plenty, " the roiling theme heard nine minutes in, and at this point Sanders and Grimes take over on tenor and bass, respectively, for the rest of the performance. Solos by Sanders, Berger, Sanders again, and Grimes (arco) precede a reprise of the theme; then, at 14 minutes, a rubato collage introduces "0m Nu" and another Sanders solo. A vamp "in two" that appears 17 minutes along sets up a Berger solo before Cherry and Sanders conclude with collective ruminations.

— Bob Blumenthal, 2005

No comments:

Post a Comment