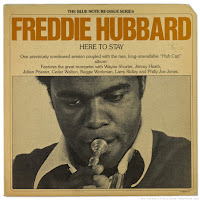

Freddie Hubbard - Here To Stay

Released - 1976

Recording and Session Information

Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, April 9, 1961

Freddie Hubbard, trumpet; Julian Priester, trombone; Jimmy Heath, tenor sax; Cedar Walton, piano; Larry Ridley, bass; Philly Joe Jones, drums.

tk.3 Earmon Jr.

tk.6 Hub Cap

tk.11 Cry Me Not

tk.15 Plexus

tk.18 Luana

tk.21 Osie Mae

Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, December 27, 1962

Freddie Hubbard, trumpet; Wayne Shorter, tenor sax; Cedar Walton, piano; Reggie Workman, bass; Philly Joe Jones, drums.

tk.4 Full Moon And Empty Arms

tk.9 Assunta

tk.18 Father And Son

tk.20 Nostrand And Fulton

tk.23 Body And Soul

tk.25 Philly Mignon

Track Listing

| Side One | ||

| Title | Author | Recording Date |

| Philly Mignon | Freddie Hubbard | 27 December 1962 |

| Father and Son | Cal Massey | 27 December 1962 |

| Body and Soul | Green-Newman-Sour-Eyton | 27 December 1962 |

| Side Two | ||

| Nostrand and Fulton | Freddie Hubbard | 27 December 1962 |

| Full Moon and Empty Arms | B. Kaye, T. Mossman | 27 December 1962 |

| Assunta | Cal Massey | 27 December 1962 |

| Side Three | ||

| Hub Cap | Freddie Hubbard | 09 April 1961 |

| Cry Me Not | Randy Weston | 09 April 1961 |

| Luana | Freddie Hubbard | 09 April 1961 |

| Side Four | ||

| Osie Mae | Freddie Hubbard | 09 April 1961 |

| Plexus | Cedar Walton | 09 April 1961 |

| Earmon Jr. | Freddie Hubbard | 09 April 1961 |

Liner Notes

FREDDIE HUBBARD

If there is one thing that is obvious about Freddie Hubbard by now — which is to say, early 1976 — it is that he is a survivor. To put it another way, his career from the day he came to New York from his native Indianapolis in 1958 has been a series of challenges which he has met head-on and emerged from triumphantly.

The very fact that Hubbard is still alive — not to mention doing extremely well — is in itself a kind of triumph. Think about it: Clifford Brown, the tempestuous trumpeter who looked like he was ready to take bop and post-bop jazz to new undreamed of heights with his mercurial style, and who was clearly the young Hubbard's primary influence, had been killed in a car accident two years before Freddie came to New York. In the late 1950's and early 1960's, when Hubbard's extensions on the Brown school of trumpet were turning heads, there were other trumpeters mining the same vein in their own personal fashion, of which probably the two most distinctive and promising were Lee Morgan, who hewed a slightly lusher and more passionately romantic course than Freddie, and Booker Little, best known for his work with Max Roach and Eric Dolphy, whose playing had a somewhat angrier edge to it and suggested a fevered quest for ever-newer expressive horizons. In late 1961, Little died of a kidney disease. In 1972, Morgan was shot to death in a now-defunct Lower East Side nightclub by a woman whose apparent motive was jealousy.

Hubbard has not only lived, he has developed into one of the most influential improvising musicians of his generation. He has participated in two of the most stimulating small bands of the 1960's, Art Blakey's (where he replaced Lee Morgan) and Max Roach's (where Booker Little, and earlier, Clifford Brown had also worked). He has also participated in two of the most outrageous, courageous and monumental experiments in improvisation ever attempted — Ornette Coleman's double-quartet album "Free Jazz" in 1961 and John Coltrane's "Ascension" in 1965. And he has emerged in the middle 1970's — a period hailed by some as a resurgence of jazz, although objectively the only thing apparent is that it's a period of considerable change and confusion in the music — as one of the few jazz musicians to make the controversial "crossover" into popular acceptance while still holding on to a strong musical identity. The jury may still be out on how successfully, aesthetically speaking, he has met this most recent challenge, but he is certainly dealing with it in a way that cannot be categorically dismissed as a sellout.

The evidence is irrefutable: Freddie Hubbard is an important musician. Even if he were to announce his retirement today — even if all copies of everything he ever recorded were to disappear — there would be a constant reminder of his contribution simply in the vast number of trumpeters whose playing has been touched by his, a list that would take you from Charles Tolliver to Randy Brecker to Woody Shaw to Hannibal Marvin Peterson to, maybe, your neighbor's kid who plays in an r&b band at high school dances.

But his importance was apparent even before his influence became widespread. In the early 1960's, when the two albums contained in this collection — one of which has never been previously released — were recorded, Hubbard was already becoming known for his work with Blakey. The various edition of Blakey's Jazz Messengers over the years have always served as proving-grounds for young musicians, a super-charged environment in which, goaded on by the persistent thunder of the leader's drums, they are forced to put up or shut up, get their act in shape or start thinking about a career outside of music. ("He's supposed to give you the message, you're supposed to carry it on," Hubbard recently said in an interview with Cadence magazine's Bob Rusch. "When you first join Art Blakey's group he tells you 'Look, I don't expect you to stay with me forever, I'm just supposed to train you and then get you ready for the business as well as the music.'")

Out of the dynamic Blakey incubator have come some of the outstanding voices in modern Jazz, not least among them the aforernentioned Clifford Brown and Hubbard's now fallen fellow-carrier of the Brown legacy, Lee Morgan. As the outstanding institution of what used to be called "hard bop," the Jazz Messengers offered a pretty thorough schooling in how to play with energy, dexterity and a kind of gutsy lyricism on sophisticated chord structures, Freddie thrived in the Messengers' idiom and obviously felt at home in it, as evidence on the sessions included here, one of which features the same instrumentation as the Messengers (trumpet, tenor sax, trombone and rhythm section) and the other of which features three fellow Messengers in the supporting cast.

But Hubbard was young, vigorous and adventurous, and in 1961, the year he joined Blakey and the year the sextet album here was recorded, there was a very new and very different kind of jazz in the air, one that a lot of the musicians Freddie was running with were immersed in. It was a music that rejected some of the basic elements of jazz that Blakey's band took for granted — a fixed harmonic pattern, a tonal center, a steady rhythmic pulse — while approaching other basic elements, such as freedom of individual expression, from a whole new perspective. The focal point of the new movement was, of course, Ornette Coleman, and Hubbard put Ornette's story succinctly in his talk with Rusch: "I would say during that period, when he first came to New York, he revolutionized music. When he came in everybody was be-bopping —Monk, Miles. He came in with this broken rhythm playing and everybody said "What?"

Some of the people who said "What?" decided that this new thing was at worst a complete shuck and at best a bunch of well-intentioned chaos. Others took a hard listen and decided it opened the door to a whole new level of artistic consciousness. There was seemingly no middle ground. But the cocky trumpeter from Indianapolis, although he remained at heart a modern traditionalist, was unafraid to plunge into the depths of free jazz, and specifically of "Free Jazz," Ornette's historic 1961 recording.

In recalling that session, Hubbard has said that he was originally reluctant to participate; he had worked and recorded with Eric Dolphy, another participant on the album, who was exploring terrain similar to Ornette's but in a more structured context, but he had never actually had to perform in a situation where it was "sound and feeling" that dictated the course of a solo instead of chord changes. The experience was, he said in 1975, "the most challenging date I ever made in my life" because "1 couldn't depend on any of my old clichés." A listen to "Free Jazz" now shows that Hubbard remained a hard-bopper at heart even in the midst of it all — the difference between Hubbard's conception and the almost manic looseness of Don Cherry, the other trumpeter on the date, is considerable — but that the 23-year-old Indianan did indeed rise to the challenge of the occasion, and did in fact manage to steer clear of his "old clichés" in a way that led to an increased awareness of his potential as a musical individual.

Throughout the early 1960's, Hubbard continued to keep one foot at least partly in the avant-garde, so it wasn't entirely surprising that in 1965 John Coltrane, with whom he had worked before, used him on his album 'Ascension," a turning point in Coltrane's career and in the overall growth of modern music that was similar in conception to "Free Jazz" but more charged, more ferocious, more emotionally unrestrained (and in consequence, harder to listen to —though equally rewarding). As exciting as his contribution to the session is, however, it was apparently right around this period in his career that Hubbard decided this particular musical context was one he would never be entirely comfortable in.

If the account Hubbard once gave to Down Beat's Neil Tesser is to be believed, his disillusionment with the avant garde came shortly after he recorded an album for Blue Note called "The Breaking Point," one of his most adventurous recordings. He had split with Blakey and formed a quintet, featuring his homeboy James Spaulding on alto sax and flute, that made that record and, Hubbard said, rehearsed for six months in preparation for their debut gig at a Cincinnati nightclub. The recorded evidence suggests that the group, while a step or two removed from the hard-bop idiom, was not exactly touching the outermost limits of free jazz; still, it was unquestionably an uncompromising and forward-looking ensemble.

What happened at the Cincinnati gig, as Hubbard related it to Tesser, is that, opening to a packed house, "I started into my free-form stuff. rand the place got empty." The lesson he learned from that experience, Hubbard alleged, was that in order for a musician to keep a group together he has to make concessions to his listeners.

I have my doubts about the strict, factual accuracy of that account. It sounds suspiciously like an attempt to justify some of the more blatantly condescending things Hubbard has stooped to in the current electrified-funk stage of his career. The story suggested by listening to Hubbard on records over the last decade is simply that he had taken what he could use from his experiences with Coleman and Coltrane, as all great musicians take what they can use from all their musical experiences, and used those elements that fit most comfortably into his own style, which he continued to develop, He has remained a proponent of a basically hard-bop style; his roots in the fast-paced, melodic, clarion sound of Clifford Brown still shine through, but there is a broad range of harmonic and coloristic elements that come out of his own varied musical history.

Although these recordings were made early in Hubbard's career, before he had had the opportunity to absorb all of his influences fully, there is still a discernible maturity in his playing and a clear indication of the huge talent that was to eventually become even more obvious. He flubs a high note here and there; his youthful enthusiasm occasionally leads him down the path of excess; but the fire, the power, and the wit are there in abundance.

The key word for Hubbard's performance on both sessions is confidence. Of late Freddie has been making his self-confidence a part of his public personna to such a degree that it has turned a lot of listeners off (it is not unusual these days for him to refer to himself on stage as "the world's greatest trumpet player," or to say of the music his group plays, "we don't call it jazz — we call it Freddie Hubbard music"), but there can be no doubt that his pride in his ability is both legitimate and justified. He once claimed that when he first arrived in New York, he was so intimidated by the scene that he didn't venture out of the house he was living in for a month, but if that's true it must surely have been the only time in his career that he manifested anything like reticence, and he obviously got over it in a hurry. On "Hub Cap," the 1961 sextet album reissued here, Hubbard surrounded himself with some formidable sidemen, notably two Philadelphians with impeccable credentials, saxophonist Jimmy Heath and drummer Philly Joe Jones, and managed to play with a take-charge kind of assurance not entirely expected from a 23-year-old just three years out of a Midwestern city hardly known as a jazz haven (although it did produce, among others, Wes Montgomery and his brothers — and Larry Ridley, the bassist on the date). The following year, when he made the quintet album which, although Blue Note went so far as to give it a title ("Here To Stay") and a catalogue number, was never issued, he was even more in command of himself and his situation.

The years when both albums were recorded were a period of remarkable excitement and activity at Blue Note — in retrospect it seems astounding how many young, adventurous players were turning out high-quality music for the label, especially when one realizes what a relatively small audience the music was reaching (which is not to say that the great Blue Note albums of the early 1960's were a well-kept secret, or that the participants were guilty of a narrow-minded cultural elitism, but only that the particular kind of fiery, explorative jazz that was the hallmark of those years at Blue Note was a little too straight-ahead to reach the majority of the record-buying public — which may have been one reason the music thrived, since the artists involved pretty much knew that whatever they played they'd have a ready-made audience that was not likely to move either above or below a certain number). Hubbard was in the center of the Blue Note post-bop maelstrom, both as leader and sideman — he recorded prolifically for the label with Blakey and such other leaders as Bobby Hutcherson and Herbie Hancock. He fit right into the hot and heavy musical milieu which mixed elements of bop, free jazz, the modal music that Coltrane and others were experimenting with at the time, and down-home funk to produce sounds that, as has been written so often it hardly bears repeating, served as a welcome relief from the increasingly effete and restrained sounds of "cool" or "West Coast" jazz.

Hubbard was in a way the ideal Blue Note musician. His demonstrative way of attacking the trumpet owed, as I've said, a great deal to Clifford Brown, and also to the men Clifford listened to, Fats Navarro and Dizzy Gillespie. It goes beyond that, though the history of jazz really isn't as cut and dried as all this, but you could pretty much draw a line all the way back to Louis Armstrong and all the way forward again to Hubbard and what you would have would be a list of trumpet players whose approach emphasizes the brassy nature of the instrument — its attention-getting volume; its power in the upper registers, the golden clarity of its sound. That's the way most jazz trumpeters have always approached the instrument, but at the time Freddie came along the influence of Miles Davis had led a lot of trumpeters to opt for an introspective, moody, almost wispy approach to the horn. This sound—which, in other trumpeters' hands tended to be a lot wispier, sometimes to the point of sounding weaker than Miles, who always had a certain force behind all that introspection, ever intended — was a major component of the "cool" sound that the Blue Note bunch of newcomers rejected. The Blue Note sound of the early 1960's was largely a return to a more full-bodied and hard-hitting approach to jazz than had been in fashion, and Hubbard, the brassiest of brass players, fit right in.

You can hear that right off the bat here on "Philly Mignon," a Hubbard original dedicated to (and made something special by) drummer Philly Joe Jones, a participant in both sessions and a major mover and shaker of the whole hard-bop movement. Jones, best known for his years with Miles — he was one reason why Davis never sounded as quiet and polite as his imitators — is a remarkable percussionist whose approach to the drum kit is a kind of synthesis of the complementary styles of Max Roach, with whom Hubbard was to serve an instructive stint in 1965, and Blakey. It combines the raw, tidal-wave emotionalism of Blakey's playing with the more carefully worked-out melodic patterns of Roach's. The result is a sound that is propulsive and conversational at the same time—he keeps up a constant chatter of commentary and counter-melody, especially on the cymbals, but never forgets to push the rhythm ferociously, especially on the bass drum. on "Philly Mignon," he and Hubbard keep urging one another on to almost orgasmic heights of intensity, the trumpeter racing to the stratosphere, the drummer playfully on his tail all the way, finally getting a chance to dance into the spotlight alone after equally volatile solos by Wayne Shorter and Cedar Walton — who, along with the bassist Reggie Workman, were working alongside Hubbard in the Blakey band at the time this album was made.

With Jones playing the Blakey role of keeping the soloists on their toes, Hubbard and cohorts sparkle forcefully through the rest of the set, an intriguing mixed bag which includes two haunting originals by the late trumpeter Cal Massey, whose skills as a composer seem to have gone largely unnoticed by everybody except his fellow musicians. No other track here is quite as charged as that opener, but there is an underlying power to even the mellower moments that comes out not only in the typically crackling, soaring trumpet playing, but also in Wayne Shorter's tenor work, which, booted by Philly Joe, sounds a little less relaxed and reflective than it sometimes has in other contexts (dig how hard he plays on "Full Moon and Empty Arms"). Hubbard himself is so full of energy on this session that even the one ballad — "Body and Soul," a tune every jazz artist wants a crack at on record at least once and Hubbard himself was to record again for Impulse a year later — comes out sounding far more affirmative and less sentimental than it usually does. Hubbard had not yet developed all the delicacy in his handling of such material that he would in subsequent years, especially after he began doubling on the rounder-toned flugelhorn, but his "Body and Soul" is certainly a creditable and emotionally solid performance.

On the "Hub Cap" session, Hubbard placed himself in a musical situation identical in instrumentation to the Jazz Messengers but audibly different because of the difference in the musicians — Jones offering a busier and less thunderous backing than Blakey, Jimmy Heath offering a more bebop-based conception on tenor than Shorter, and Julian Priester offering a somewhat less gruff and more lyrical trombone style than Curtis Fuller, including occasional forays into the horn's upper register. But the main order of the day was the same as it was (and is, and always will be) with Blakey — forceful, almost violently swinging improvisation. Freddie is in rare form on the title track, his solo offering the tension of rapid bursts of melody alternating with stately held notes. Everyone sounds doubly inspired on "Luana, another original by Hubbard that has a captivatingly simple folksong-like melody and a powerful ensemble section near the end, built around Philly Joe, that may take the top of your head off the first time you hear it. Walton's tune "Plexus," a staple of the Blakey repertoire at the time, is a kind of musical fireworks display, with Jones' colorful, constantly-shifting drum patterns offering the impetus for a string of solos that all—Hubbard's and Heath's especially — just about palpably throb with vitality. And pianist Randy Weston's "Cry Me Not," which, like "Body and Soul" on the quintet session, is the date's only ballad, is a fascinating melody, a short but bittersweet reflection on love that, as orchestrated by trombonist-arranger Melba Liston, highlights Hubbard at his most passionate.

Freddie Hubbard today is in the midst of the kind of commercial success that none of the artists in the Blue Note stable of the early 1960's had any reason to expect. Although a lot of what he is playing these days has to do with effects and gimmickry, it would be a gross oversimplification to say, as some purists have charged, that he has achieved his success by changing his approach to his music and turning his back on the artistic values that made his work for Blue Note so good. That simply isn't true. In purely technical terms, Hubbard is a better trumpet player now than he ever was, and if the emphasis on the electrified and the disco-danceable sometimes overshadows other aspects of a Hubbard performance these days, the fact is that those aspects are still there. Only if he were to stop playing the trumpet altogether would he stop being a wailing. smoking bitch of a trumpet player. The Freddie Hubbard who is basking in a degree of genuine stardom today is the same Freddie Hubbard who, just a few years out of Indianapolis, made these records in the early 1960's — a player of imagination, strength, dexterity, and tremendous spirit. It is good to see people responding to his playing in such numbers today, and it is good to have material like this made widely available, to remind everybody of just how much Freddie Hubbard exists on wax, and just how good most of it is,

PETER KEEPNEWS

No comments:

Post a Comment